- Home

- Jules Verne

The Mysterious Island Page 10

The Mysterious Island Read online

Page 10

"I have often marvelled, my dear friends, and I marvel still at all you have done in this corner of your island. Rock Castle, Falconhurst, Prospect Hill, your farms, your plantations, your fields, all prove your intelligence to be as great as your courage in hard work. But I have already asked Mme. Zermatt how it is that you have not got—"

"A chapel," Betsy answered quickly. "You are right, Merry dear, and we do undoubtedly owe it to God to build to His glory—"

"Something better than a chapel—a temple," exclaimed Jack, whom nothing ever dismayed; "a monument with a splendid steeple! When shall we begin, Papa? There is material enough and to spare. Mr. Wolston will draw the plans and we will carry them out."

"Excellent!" replied M. Zermatt with a smile; "but if I can see the temple with my mind's eye, I cannot see the pastor, the preacher."

"Frank will be that when he comes back," said Ernest.

"Meantime do not let that worry you, M. Zermatt,"

Mrs. Wolston put in. "We will content ourselves with saying our prayers in our chapel."

"It is an excellent idea of yours, Mrs. Wolston, and we must not forget that new colonists will be coming very soon. So we will look carefully into the matter in our spare time during the rainy season. We will look for a suitable site."

"It seems to me, dear," said Mme. Zermatt, "that if we cannot use Falconhurst as a dwelling place any longer, it would be quite easy to alter it into an aerial chapel."

"And then our prayers would be half way to heaven already, as Frank would remark," Jack added.

"It would be a little too far from Rock Castle," M. Zermatt replied. "I think it would be better to build this chapel near our principal residence, round which new houses will gradually gather. But, as I said before, we will look carefully into the idea."

During the three or four months which remained of the fine weather all hands were employed in the most pressing work, and from the 15th of March until the end of April there was not a single holiday. Mr. Wolston did not spare himself; but he could not take the place of Fritz and Frank in providing the farmsteads with fodder for the winter keep. There were now a hundred sheep, goats and pigs at Wood Grange; the hermitage at Eberfurt and Prospect Hill, and the cattlesheds at Rock Castle would not have been large enough to accommodate all this stock. The poultry was all brought into the poultry yard before the rainy season, and the fowls, bustards, and pigeons were attended to there every day. The geese and ducks could amuse themselves on the pond, a couple of gunshots away. It was only the draught cattle, the asses and buffaloes, and the cows and their calves that never left Rock Castle. Thus, irrespective of hunting and fishing, which were still very profitable from April to September, supplies were guaranteed merely from the produce of the yards.

On the 15th of March, however, there was still a good week before the field work would require the service of all hands. So, during that week, there would be no harm done by devoting the whole time to some trip outside the confines of the Promised Land. And this was the topic of conversation between the two families in the evening.

Mr. Wolston's knowledge was limited to the district between Jackal River and False Hope Point, including the farms at Wood Grange, the hermitage at Eberfurt, Sugar-cane Grove and Prospect Hill.

"I am surprised, Zermatt," he said one day, "that in all these twelve years neither you nor your children have attempted to reach the interior of New Switzerland."

"Why should we have tried, Wolston?" M. Zermatt replied. "Think! When the wreck of the Landlord cast us on this shore, my boys were only children, incapable of accompanying me on a journey of exploration. My wife could not have gone with me, and it would have been most imprudent to leave her alone."

"Alone with Frank, who was only five years old,"

Mme. Zermatt put in. "And besides, we had not abandoned hope of being picked up by some ship."

"Before all else," M. Zermatt went on, "it was a matter of providing for our immediate needs and of staying in the neighbourhood of the ship until we had taken out of her every single thing that might be useful to us. At the mouth of Jackal River we had fresh water, fields that could be cultivated easily on its right bank, and plantations all ready grown not far away. Soon afterwards, quite by chance, we discovered this healthy and safe dwelling place at Rock Castle. Ought we to have wasted time merely satisfying our curiosity?"

"And besides," Ernest remarked, "might not leaving Deliverance Bay have meant exposing ourselves to the chance of meeting natives, like those of the Nicobars and Andamans perhaps who are such fierce savages?"

"At all events," M. Zermatt went on, "each day brought some task that sheer necessity forbade us to postpone. Each new year imposed upon us the work of the year before. And gradually, with habits formed and an accustomed sense of well-being, we struck down roots in this spot, if I may use the phrase; that is why we have never left it. So the years have gone by, and it seems only yesterday that we first came here. What would you have had us do, Wolston? We were very well off here, in this district, and it did not occur to us that it would be wise to go out of it to look for anything better."

"That is all perfectly reasonable," Mr. Wolston answered, "but for my part, I could not have resisted for so many years my desire to explore the country towards the south, east and west."

"Because you are an Englishman," M. Zermatt replied, "and your native instinct urges you to travel. But we are Swiss, and the Swiss are a peaceful, stay- at-home people who never leave their mountains without regret; and if circumstances had not compelled us to leave Europe—"

"I protest, Papa!" Jack answered. "I protest, so far as I am concerned. Thorough Swiss as I am, I should have loved to travel all over the world!"

"You ought to be an Englishman, Jack," Ernest declared, "and please understand that I do not blame you a bit for having this inborn desire to move about. Besides, I think that Mr. Wolston is right. It really is necessary that we should make a complete survey of this New Switzerland of ours."

"Which is an island in the Indian Ocean, as we know now," Mr. Wolston added; "and it would be well to do it before the Unicorn comes back."

"Whenever Papa likes," exclaimed Jack, who was always ready to take a hand in any new discovery.

"We will talk about that again after the rainy season," M. Zermatt said. "I have not the least objection to a journey into the interior. But let us acknowledge that we were highly favoured in being permitted to land upon this coast which is both healthy and fertile. Is there another equal to it?"

"How do we know?" Ernest answered. "It is true, the coast we passed in the pinnace, when we doubled Cape East on our way to Unicorn Bay, was nothing but naked rocks and dangerous reefs, and even where the corvette was moored there was nothing but sandy shore. But beyond that, to the southward, it is quite likely that New Switzerland presents a less desolate appearance."

"The way to make sure of that," said Jack, "is to sail all round it in the pinnace. We shall know then what its configuration is."

"But if you have never been beyond Unicorn Bay to the eastward," Mr. Wolston insisted, "you have been much further along the northern coast."

"Yes, for something like forty miles," Ernest answered; "from False Hope Point to Pearl Bay."

"And we had not even the curiosity to go to see Burning Rock," Jack exclaimed.

"A desert island, which Jenny never wanted to see again," Hannah remarked.

"The best thing to do," M. Zermatt decided, "will be to explore the territory near the shore of Pearl Bay, for beyond that there are green prairies, broken hills, fields of cotton trees, with leafy woods."

"Where are the truffles!" Ernest put in.

"You glutton!" Jack exclaimed.

"Yes, truffles," M. Zermatt replied, laughing, "and where there are creatures too that dig the truffles up."

"Not forgetting panthers and lions!" Betsy added.

"Well," said Mr. Wolston, "the net result of all that is that we must not venture that way or any other without takin

g precautions. But since our future colony will be obliged to spread beyond the Promised Land, it seems to me that it would be better to explore the interior than to sail round the island."

"And to do so before the corvette comes back," Ernest added. "My view, indeed, is that it would be best to cross the defile of Cluse and go through the Green Valley so as to get right up to the mountains that one can see from the rising ground at Eberfurt."

"Did they not seem a very long way off from you?" Mr. Wolston asked.

"Yes; about twenty-five miles," Ernest replied.

"I am sure Ernest has mapped out a journey already," said Hannah with a smile.

"I confess I have, Hannah," the young man answered, "and I am longing to be able to draw an accurate map of the whole of our New Switzerland."

"My good people," said M. Zermatt, "this is what I suggest to begin to satisfy Mr. Wolston."

"Agreed to in advance!" replied Jack.

"Wait, you impatient fellow! It will be ten or twelve days before we are required for the second harvest, and if you like we will spend half that time in visiting the portion of the island which skirts the eastern shore."

"And while M. Zermatt with his two sons and Mr. Wolston are on this trip," Mrs. Wolston objected disapprovingly, "Mme. Zermatt, Hannah and I are to remain alone at Rock Castle; is that it?"

"No, Mrs. Wolston," M. Zermatt answered; "the pinnace will hold us all."

"When do we start?" cried Jack. "To-day?"

"Why not yesterday?" M. Zermatt answered, with a laugh.

"Since we have surveyed the inside of Pearl Bay already," said Ernest, "it really is better to follow up the eastern coast. The pinnace would go straight to Unicorn Bay and then southwards. We might perhaps discover the mouth of some river which we might ascend."

"That is an excellent idea," M. Zermatt declared.

"Unless perhaps it were better to make a circuit of the island," Mr. Wolston remarked.

"The circuit of it?" Ernest replied. "Oh, that would take more time than we have to give, for when we made our first trip to the Green Valley we could only make out the faint blue outline of the mountains on the horizon."

"That is precisely what it is important to have accurate information about," Mr. Wolston urged.

"And what we ought to have known all about long ago," Jack declared.

"Then that is settled," said M. Zermatt in conclusion; "perhaps we shall find on this east coast the mouth of a river which it will be possible to ascend, if not in the pinnace at any rate in the canoe."

And the plan having been agreed upon, it was decided to make a start on the next day but one.

As a matter of fact, thirty-six hours was none too long a time to ask for preparation. To begin with, the Elizabeth had to be got ready for the voyage, and at the same time provision had to be made for the feeding of the domestic animals during an absence which might perhaps be protracted by unforeseen circumstances.

So one and all had quite enough to get through.

Mr. Wolston and Jack made it their business to inspect the pinnace which was moored in the creek. She had not been to sea since her trip to Unicorn Bay. Some repairs had to be done, and Mr. Wolston was clever at this. Navigation would be no new thing to him, and Jack, too, could be relied upon, as the fearless successor to Fritz, to handle the Elizabeth as he handled the canoe.

M. Zermatt and Ernest, Mme. Zermatt, Mrs. Wolston and Hannah, were entrusted with the duty of providing the cattlesheds and the poultry yard with food, and they did it conscientiously. There was a large quantity left of the last harvest. Being graminivorous, the buffaloes, onager, asses, cows and the ostrich would lack nothing. The fowls, geese, ducks, Jenny's cormorant, the two jackals, the monkey, were made as sure of their food supply. Brownie and Fawn were to be taken, for there might be need to hunt on this trip, if the pinnace put in at any point on the coast.

All these arrangements of course made visits necessary to the farmsteads at Wood Grange, the hermitage at Eberfurt, Sugar-cane Grove, and Prospect Hill, among which the various animals were distributed. All these places were carefully kept in a state to receive visitors for a few days. But with the help of the waggon, the delay of thirty-six hours, stipulated for by M. Zermatt, was not exceeded.

There really was no time to be lost. The yellowing crops were on the point of ripening. The harvest could not be delayed beyond a fortnight, and the pinnace must be back by that time.

At last, in the evening of the 14th of March, a case of preserved meat, a bag of cassava flour, a cask of mead, a keg of palm wine, four guns, four pistols, powder, lead, enough shot for the Elizabeth's two small cannon, bedding, linen, spare clothes, oilskins, and cooking utensils were put on board.

Everything being ready for the start, all that had to be done was to take advantage, at the very first break of day, of the breeze which would blow off the land in order to reach Cape East.

After a peaceful night the two families went on board, at five o'clock in the morning, accompanied by the two dogs which gambolled and frolicked to their hearts' content.

As soon as the party had all taken their place on deck, the canoe was triced up aft. Then, with mainsail, foresail, and jib set, with M. Zermatt at the helm and Mr. Wolston and Jack on the look-out, the pinnace picked up the wind, and after passing Shark's Island speedily lost sight of the heights of Rock Castle.

CHAPTER VIII - EXPLORERS OF UNKNOWN COASTS

AS soon as she had cleared the entrance to the bay r the pinnace glided over the surface of the broad expanse of sea between False Hope Point and Cape East. The weather was fine. The grey-blue sky was tapestried with a few clouds through which the sun's rays filtered.

At this early morning hour the breeze blew off the land and was favourable to the progress of the Elizabeth. It would not be until she had rounded Cape East that she would feel the wind from the sea.

The light vessel was carrying all her brig sails, even a flying jib and the pole sails of her two masts. To the swing of the open sea, with full sails, and a list to her starboard quarter, she clove the water, as still as that of a lake, and sped along at eight knots, leaving a long track of rippling foam in her wake.

What thoughts thronged Mme. Zermatt's mind, what memories of these twelve years that had passed! She saw again in fancy the tub boat roughly improvised for their rescue, which the least false stroke might have capsized; that frail contrivance making for an unknown shore with all that she loved within it, her husband, and her four sons, of whom the youngest was barely five years old; then she was landing at the mouth of Jackal River, and the first tent was set up at the spot which was Tent Home before it became Rock Castle.

And what fears were hers whenever M. Zermatt and Fritz went back to the wreck! And now here she was, upon this well-rigged, well-handled pinnace, a good sea-boat, sharing without a tremor of fear in this voyage of discovery round the eastern coast of the island.

What changes, too, there had been in the last five months, and what changes, more important still, perhaps, could be anticipated within the very near future!

M. Zermatt was manoeuvring so as to make the best use of the wind which tended to die away as the Elizabeth drew farther away from the land. Mr. Wolston, Ernest, and Jack stood by the sheets ready to haul them taut or ease them as need might be. It would have been a pity to become becalmed before coming off Cape East, where the pinnace would catch the breeze from the open sea.

Mr. Wolston said:

"I am afraid the wind is scanting; see how our sails are sagging!"

"The wind certainly is dropping," M. Zermatt answered, "but since it is blowing from aft let us put the foresail one side and the mainsail the other. We are sure to gather some pace that way."

"It should not take us more than half an hour to round the point," Ernest remarked.

"If the breeze drops altogether," Jack suggested,

"we have only to put out the oars and paddle as far as the cape. With four of us at it the pinnace won't stay still, I s

hould imagine."

"And who will take the tiller while you are all at the oars?" Mme. Zermatt enquired.

"You will, mamma, or Mrs. Wolston, or even Hannah," Jack replied. "Why not Hannah? I am sure she would shove the tiller to port or starboard as well as any old salt?"

"Why not?" answered the girl, laughing. "Especially if I have only to do what you tell me, Jack."

"Good! It is as easy to manage a boat as it is to manage a house, and, of course, all women are adepts at that from the start," Jack answered.

There was no need to resort to the oars, or to what would have been much simpler—towing by the canoe. As soon as the two sails had been set crosswise the pinnace obeyed the breeze more readily and made appreciable progress towards Cape East.

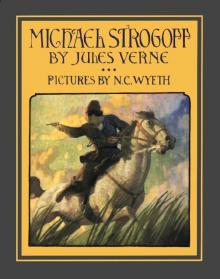

Michael Strogoff; Or the Courier of the Czar: A Literary Classic

Michael Strogoff; Or the Courier of the Czar: A Literary Classic Voyage au centre de la terre. English

Voyage au centre de la terre. English Journey Through the Impossible

Journey Through the Impossible The Castaways of the Flag

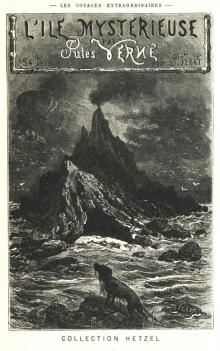

The Castaways of the Flag L'île mystérieuse. English

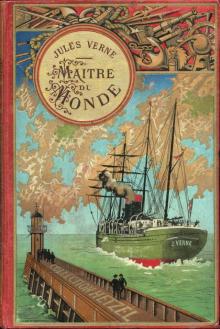

L'île mystérieuse. English Maître du monde. English

Maître du monde. English Around the World in Eighty Days

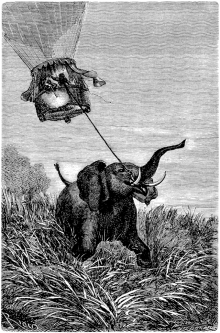

Around the World in Eighty Days A Voyage in a Balloon

A Voyage in a Balloon From the Earth to the Moon, Direct in Ninety-Seven Hours and Twenty Minutes: and a Trip Round It

From the Earth to the Moon, Direct in Ninety-Seven Hours and Twenty Minutes: and a Trip Round It Paris in the Twentieth Century

Paris in the Twentieth Century City in the Sahara - Barsac Mission 02

City in the Sahara - Barsac Mission 02 The English at the North Pole

The English at the North Pole The Field of Ice

The Field of Ice From the Earth to the Moon

From the Earth to the Moon Un capitaine de quinze ans. English

Un capitaine de quinze ans. English The Mysterious Island

The Mysterious Island Les indes-noirs. English

Les indes-noirs. English Robur-le-conquerant. English

Robur-le-conquerant. English Propeller Island

Propeller Island Around the World in Eighty Days. Junior Deluxe Edition

Around the World in Eighty Days. Junior Deluxe Edition Les forceurs de blocus. English

Les forceurs de blocus. English In the Year 2889

In the Year 2889 Journey to the Centre of the Earth

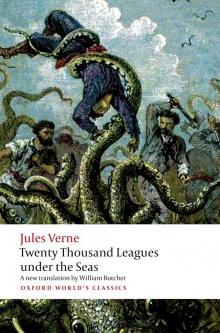

Journey to the Centre of the Earth Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea From the Earth to the Moon; and, Round the Moon

From the Earth to the Moon; and, Round the Moon Vingt mille lieues sous les mers. English

Vingt mille lieues sous les mers. English Cinq semaines en ballon. English

Cinq semaines en ballon. English Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas

Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas Face au drapeau. English

Face au drapeau. English Michael Strogoff; Or, The Courier of the Czar

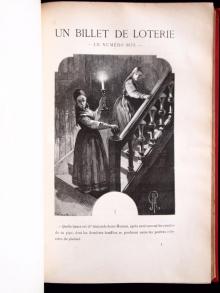

Michael Strogoff; Or, The Courier of the Czar Un billet de loterie. English

Un billet de loterie. English The Secret of the Island

The Secret of the Island Off on a Comet! a Journey through Planetary Space

Off on a Comet! a Journey through Planetary Space Into the Niger Bend: Barsac Mission, Part 1

Into the Niger Bend: Barsac Mission, Part 1 All Around the Moon

All Around the Moon A Journey to the Center of the Earth - Jules Verne: Annotated

A Journey to the Center of the Earth - Jules Verne: Annotated 20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 2

20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 2 Robur-le-Conquerant

Robur-le-Conquerant Les Index Noires

Les Index Noires Michael Strogoff; or the Courier of the Czar

Michael Strogoff; or the Courier of the Czar 20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 1

20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 1 Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Five Weeks In A Balloon

Five Weeks In A Balloon Journey to the Center of the Earth

Journey to the Center of the Earth 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday

Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday The Collected Works of Jules Verne: 36 Novels and Short Stories (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics)

The Collected Works of Jules Verne: 36 Novels and Short Stories (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics) The Survivors of the Chancellor

The Survivors of the Chancellor Their Island Home

Their Island Home Le Chateau des Carpathes

Le Chateau des Carpathes Les Cinq Cents Millions de la Begum

Les Cinq Cents Millions de la Begum The Floating Island

The Floating Island Cinq Semaines En Ballon

Cinq Semaines En Ballon Autour de la Lune

Autour de la Lune