- Home

- Jules Verne

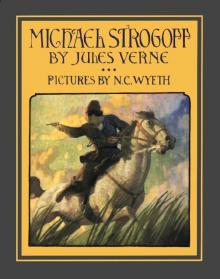

Michael Strogoff; Or the Courier of the Czar: A Literary Classic Page 13

Michael Strogoff; Or the Courier of the Czar: A Literary Classic Read online

Page 13

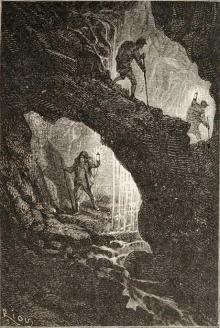

In fact, two hours were taken up in making the passage of the Ichim, which much exasperated Michael, especially as the boatmen gave them alarming news of the Tartar invasion.

This is what they raid:

Some of Feofar-Khan’s scouts had already appeared on both banks of the lower Ichim, in the southern parts of the government of Tobolsk. Omsk was threatened. They spoke of an engagement which had taken place between the Siberian and Tartar troops on the frontier of the great Kirghese horde—an engagement which had not been to the advantage of the Russians, who were somewhat weak in numbers in that direction. The troops had retreated thence, and in consequence there had been a general emigration of all the peasants of the province. The boatmen spoke of horrible atrocities committed by the invaders—pillage, theft, incendiarism, murder. Such was the system of Tartar warfare.

The people fled on all sides before Michael Feofar-Khan. Michael Strogoff’s great fear was lest, in the depopulation of the towns and hamlets, he should be unable to obtain the means of transport. He was therefore extremely anxious to reach Omsk. Perhaps on leaving this town they would get the start of the Tartar scouts, who were coming down the valley of the Irtych, and would find the road open to Irkutsk.

Just at the place where the tarantass crossed the river ended what is called, in military language, the “Ichim chain”—a chain of towers, or little wooden forts, extending from the southern frontier of Siberia for a distance of nearly four hundred versts. Formerly these forts were occupied by detachments of Cossacks, and they protected the country against the Kirghese, as well as against the Tartars. But since the Muscovite Government had believed these hordes reduced to absolute submission, they had been abandoned, and now could not be used, just at the time when they would have been most useful. Many of these forts had been reduced to ashes; and the boatmen even pointed out the smoke to Michael, rising in the southern horizon, and showing the approach of the Tartar advance-guard.

As soon as the ferryboat landed the tarantass and its occupants on the right bank of the Ichim, the journey across the steppe was resumed with all possible speed.

It was seven in the evening. The sky was cloudy. Every now and then a shower of rain fell, which laid the dust and much improved the roads. Michael Strogoff had remained very silent from the time they left Ichim. He was, however, always attentive to Nadia, helping her to bear the fatigue of this long journey without break or rest; but the girl never complained. She longed to give wings to the horses. Something told her that her companion was even more anxious than herself to reach Irkutsk; and how many versts were still between!

It also occurred to her that if Omsk was entered by the Tartars, Michael’s mother, who lived there, would be in danger, about which her son would be very uneasy, and that this was sufficient to explain his impatience to get to her.

Nadia at last spoke to him of old Marfa, and of how unprotected she would be in the midst of all these events.

“Have you received any news of your mother since the beginning of the invasion?” she asked.

“None, Nadia. The last letter my mother wrote to me contained good news. Marfa is a brave and energetic Siberian woman. Notwithstanding her age, she has preserved all her moral strength. She knows how to suffer.”

“I shall see her, brother,” said Nadia quickly. “Since you give me the name of sister, I am Marfa’s daughter.”

And as Michael did not answer she added:

“Perhaps your mother has been able to leave Omsk?”

“It is possible, Nadia,” replied Michael; “and I hope she may have reached Tobolsk. Marfa hates the Tartars. She knows the steppe, and would have no fear in just taking her staff and going down the banks of the Irtych. There is not a spot in all the province unknown to her. Many times has she travelled all over the country with my father; and many times I myself, when a mere child, have accompanied them in their journeys across the Siberian desert Yes, Nadia, I trust that my mother has left Omsk.”

“And when shall you see her?”

“I shall see her—on my return.”

“If, however, your mother is still at Omsk, you will be able to spare an hour to go to her?”

“I shall not go and see her.”

“You will not see her?”

“No, Nadia,” answered Michael, his chest heaving as he felt that he could not go on replying to the girl’s questions.

“You say no! Why, brother, if your mother is still at Omsk, for what reason could you refuse to see her?”

“For what reason, Nadia? You ask me for what reason,” exclaimed Michael, in so changed a voice that the young girl started. “For the same reason as that which made me patient even to cowardice with the villain who——”

He could not finish his sentence.

“Calm yourself, brother,” said Nadia in a gentle voice. “I only know one thing, or rather I do not know it, I feel it. It is that all your conduct is now directed by the sentiment of a duty more sacred—if there can be one—than that which unites the son to the mother.”

Nadia was silent, and from that moment avoided every subject which in any way touched on Michael’s peculiar situation. He had a secret motive which she must respect. She respected it. The next day, July 25th, at three o’clock in the morning, the tarantass arrived at the post-house in Tiou-kalmsk, having accomplished a distance of one hundred and twenty versts since it had crossed the Ichim.

They rapidly changed horses. Here, however, for the first time, the iemschik made difficulties about starting, declaring that detachments of Tartars were roving across the steppe, and that travellers, horses, and carriages would be a fine prize for such robbers.

Only by dint of a large bribe could Michael get over the unwillingness of the iemschik, for in this instance, as in many others, he did not wish to show his podorojna. The last ukase, having been transmitted by telegraph, was known in the Siberian provinces; and a Russian specially exempted from obeying these orders would certainly have drawn public attention to himself—a thing above all to be avoided by the Czar’s courier. As to the iemschik’s hesitation, either the rascal traded on the traveller’s impatience or he really had good reason to fear some misfortune.

However, at last the tarantass started, and made such good way that by three in the afternoon it had reached Koulatsinskoë, eighty versts farther on. An hour after this it was on the banks of ths Irtych. Omsk was now only twenty versts distant.

The Irtych is a large river, and one of the principal of those which flow towards the north of Asia. Rising in the Ataï Mountains, it flows from the south-east to the north-west, and empties itself into the Obi, after a course of nearly seven thousand versts.

At this time of year, when all the rivers of the Siberian basin are much swollen, the waters of the Irtych were very high. In consequence the current was changed to a regular torrent, rendering the passage difficult enough. A swimmer could not have crossed, however powerful a one he might be; and even in a ferryboat there would be some danger.

But Michael and Nadia, determined to brave all perils whatever they might be, did not dream of shrinking from this one.

However, Michael proposed to his young companion that he should cross first, embarking in the ferryboat with the tarantass and horses, as he feared that the weight of this load would render it less safe. After landing the carriage on the opposite bank he would return and fetch Nadia.

The girl refused. It would be the delay of an hour, and she would not, for her safety alone, be the cause of it.

The embarkation was made not without difficulty, for the banks were partly flooded and the boat could not get in near enough.

However, after half an hour’s exertion, the boatmen got the tarantass and the three horses on board. Michael, Nadia, and the iemschik embarked also, and they shoved off.

For a few minutes all went well. A little way up the river the current was broken by a long point projecting from the bank, and forming an eddy easily crossed by the boat The two boatmen propelled the

ir barge with long poles, which they handled cleverly; but as they gained the middle of the stream it grew deeper and deeper, until at last they could only just reach the bottom. The ends of the poles were only a foot above the water, which rendered their use difficult and insufficient. Michael and Nadia, seated in the stern of the boat, and always in dread of a delay, watched the boatmen with some uneasiness.

“Look out!” cried one of them to his comrade.

The shout was occasioned by the new direction the boat was rapidly taking. It had got into the direct current and was being swept down the river. By diligent use of the poles, putting the ends in a series of notches cut below the gunwale, the boatmen managed to keep their craft against the stream, and slowly urged it in a slanting direction towards the right bank.

They calculated on reaching it some five or six versts below the landing place; but, after all, that would not matter so long as men and beasts could disembark without accident. The two stout boatmen, stimulated moreover by the promise of double fare, did not doubt of succeeding in this difficult passage of the Irtych.

But they reckoned without an incident which they were powerless to prevent, and neither their zeal nor their skilfulness could, under the circumstances, have done more.

The boat was in the middle of the current, at nearly equal distances from either shore, and being carried down at the rate of two versts an hour, when Michael, springing to his feet, bent his gaze up the river.

Several boats, aided by oars as well as by the current, were coming swiftly down upon them.

Michael’s brow contracted, and an exclamation escaped him.

“What is the matter?” asked the girl.

But before Michael had time to reply one of the boatmen exclaimed in an accent of terror:

“The Tartars! The Tartars!”

There were indeed boats full of soldiers, and in a few minutes they must reach the ferryboat, it being too heavily laden to escape from them.

The terrified boatmen uttered exclamations of despair and dropped their poles.

“Courage, my friends!” cried Michael; “Courage! Fifty roubles for you if we reach the right bank before the boats overtake us.”

Incited by these words, the boatmen again worked manfully but it soon became evident that they could not escape the Tartars.

It was scarcely probable that they would pass without attacking them. On the contrary, there was everything to be feared from robbers such as these.

“Do not be afraid, Nadia,” said Michael; but “be ready for anything.”

“I am ready,” replied Nadia.

“Even to throw yourself into the water when I tell you?”

“Whenever you tell me.”

“Have confidence in me, Nadia.”

“I have, indeed!”

The Tartar boats were now only a hundred feet distant. They carried a detachment of Bokharian soldiers, on their way to reconnoitre round Omsk.

The ferryboat was still two lengths from the shore. The boatmen redoubled their efforts. Michael himself seized a pole and wielded it with superhuman strength. If he could land the tarantass and horses, and dash off with them, there was some chance of escaping the Tartars, who were not mounted.

But all their efforts were in vain.

“Saryn na kitchou!” shouted the soldiers from the first boat.

Michael recognized the Tartar war-cry, which is usually answered by lying flat on the ground.

As neither he nor the boatmen obeyed this injunction, a volley was let fly amongst them, and two of the horses were mortally wounded.

At the next moment a violent blow was felt. The boats had run into the ferryboat.

“Come, Nadia!” cried Michael, ready to jump over-board.

The girl was about to follow him, when a blow from a lance struck him, and he was thrown into the water. The current swept him away, his hand raised for an instant above the waves, and then he disappeared.

Nadia uttered a cry, but before she had time to throw herself after him she was seized and dragged into one of the boats.

In a few minutes the boatmen were killed, the ferryboat left to drift away, whilst the Tartars continued to descend the Irtych.

CHAPTER XIV.

MOTHER AND SON.

OMSK is the official capital of Western Siberia. It is not the most important city of the government of that name, for Tomsk has more inhabitants and is larger. But it is at Omsk that the Governor-General of this the first half of Asiatic Russia resides.

Omsk, properly so called, is composed of two distinct towns: one which is exclusively inhabited by the authorities and officials; the other more especially devoted to the Siberian merchants, although, indeed, for the matter of that, the town is of small commercial importance.

This city has about 12,000 to 13,000 inhabitants. It is defended by walls, flanked by bastions, but these fortifications are merely of earth, and could afford only insufficient protection. The Tartars, who were well aware of this fact, consequently tried at this period to carry it by main force, and in this they succeeded, after an investment of a few days.

The garrison of Omsk, reduced to two thousand men, resisted valiantly. But overwhelmed by the troops of the Emir, driven back, little by little, from the mercantile portion of the place, they were compelled to take refuge in the upper town.

It was there that the Governor-General, his officers, and soldiers had entrenched themselves. After having crenelated the houses and churches, they had made the upper quarter of Omsk a kind of citadel, and hitherto they held out well in this species of improvised “kreml,” but without much hope of the promised succour. In fact, the Tartar troops, who were descending the course of the Irtych, received every day fresh reinforcements, and, what was more serious, they were then led by an officer, a traitor to his country, but a man of much note, and of an audacity equal to any emergency.

This man was Colonel Ivan Ogareff.

Ivan Ogareff, terrible as any of the most savage Tartar chieftains, was an educated soldier. Possessing on his mother’s side, who was of Asiatic origin, some Mongolian blood, he delighted in deceptive strategy and the planning of ambuscades, stopping short of nothing when he desired to fathom some secret or to set some trap. Deceitful by nature, he willingly had recourse to the vilest trickery; lying when occasion demanded, excelling in the adoption of all disguises and in every species of deception. Further, he was cruel, and had even acted as an executioner. Feofar-Khan possessed in him a lieutenant well capable of seconding his designs in this savage war.

When Michael Strogoff arrived on the banks of the Irtych, Ivan Ogareff was already master of Omsk, and was pressing the siege of the upper quarter of the town all the more eagerly because he must hasten to repair to Tomsk, where the main body of the Tartar army had just been concentrated.

Tomsk, in fact, had been taken by Feofar-Khan some days previously, and it was thence that the invaders, masters of Central Sibera, were to march upon Irkutsk.

Irkutsk was the real object of Ivan Ogareff.

The plan of the traitor was to ingratiate himself with the Grand Duke under a false name, to gain his confidence, and in course of time to deliver into Tartar hands the town and the Grand Duke himself.

With such a town, and such a hostage, all Asiatic Siberia must necessarily fall into the hands of the invaders.

Now it was well known that the Czar was acquainted with this conspiracy, and it was for the purpose of baffling it that Michael Strogoff had been intrusted with the important missive of which he was the bearer. Hence, therefore, the very stringent instructions which had been given to the young courier to pass incognito through the invaded district.

This mission he had faithfully performed up to this moment, but now could he carry it to a successful completion?

The blow which had struck Michael Strogoff was not mortal. By swimming in a manner by which he had effectually concealed himself, he had reached the right bank, where he fell exhausted among the bushes.

When he

recovered his senses, he found himself in the cabin of a mujik, who had picked him up and cared for him, and to whom he owed his life. For how long a time had he been the guest of this brave Siberian? He could not guess. But when he opened his eyes he saw the handsome bearded face bending over him, and regarding him with pitying eyes. He was about to ask where he was, when the mujik, anticipating him, said—

“Do not speak, little father; do not speak! Thou art still too weak. I will tell thee where thou art and everything that has passed since I brought thee to my cabin.”

And the mujik related to Michael Strogoff the different incidents of the struggle which he had witnessed—the attack upon the ferry by the Tartar boats, the pillage of the tarantass, and the massacre of the boatmen.

But Michael Strogoff listened no longer, and slipping his hand under his garment he felt the imperial letter still secured in his breast.

He breathed a sigh of relief. But that was not all.

“A young girl accompanied me,” said he.

“They have not killed her,” replied the mujik, anticipating the anxiety which he read in the eyes of his guest. “They have carried her off in their boat, and have continued the descent of Irtych. It is only one prisoner more to join so many others which they are taking to Tomsk!”

Michael Strogoff was unable to reply. He pressed his hand upon his heart to restrain its beating.

But, notwithstanding these many trials, the sentiment of duty mastered his whole soul.

“Where am I?” asked he.

“Upon the right bank of the Irtych, only five versts from Omsk,” replied the mujik.

“What wound can I have received which could have thus prostrated me? It was not a gunshot wound?”

“No; a lance-thrust in the head, now healing,” replied the mujik. “After a few days’ rest, little father, thou wilt be able to proceed. Thou didst fall into the river; but the Tartars neither touched nor searched thee; and thy purse is still in thy pocket”

Michael Strogoff; Or the Courier of the Czar: A Literary Classic

Michael Strogoff; Or the Courier of the Czar: A Literary Classic Voyage au centre de la terre. English

Voyage au centre de la terre. English Journey Through the Impossible

Journey Through the Impossible The Castaways of the Flag

The Castaways of the Flag L'île mystérieuse. English

L'île mystérieuse. English Maître du monde. English

Maître du monde. English Around the World in Eighty Days

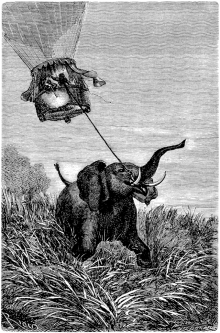

Around the World in Eighty Days A Voyage in a Balloon

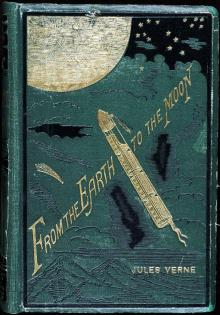

A Voyage in a Balloon From the Earth to the Moon, Direct in Ninety-Seven Hours and Twenty Minutes: and a Trip Round It

From the Earth to the Moon, Direct in Ninety-Seven Hours and Twenty Minutes: and a Trip Round It Paris in the Twentieth Century

Paris in the Twentieth Century City in the Sahara - Barsac Mission 02

City in the Sahara - Barsac Mission 02 The English at the North Pole

The English at the North Pole The Field of Ice

The Field of Ice From the Earth to the Moon

From the Earth to the Moon Un capitaine de quinze ans. English

Un capitaine de quinze ans. English The Mysterious Island

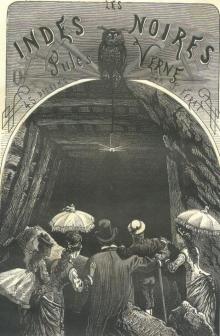

The Mysterious Island Les indes-noirs. English

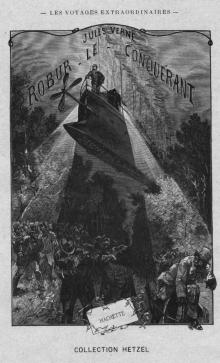

Les indes-noirs. English Robur-le-conquerant. English

Robur-le-conquerant. English Propeller Island

Propeller Island Around the World in Eighty Days. Junior Deluxe Edition

Around the World in Eighty Days. Junior Deluxe Edition Les forceurs de blocus. English

Les forceurs de blocus. English In the Year 2889

In the Year 2889 Journey to the Centre of the Earth

Journey to the Centre of the Earth Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea From the Earth to the Moon; and, Round the Moon

From the Earth to the Moon; and, Round the Moon Vingt mille lieues sous les mers. English

Vingt mille lieues sous les mers. English Cinq semaines en ballon. English

Cinq semaines en ballon. English Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas

Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas Face au drapeau. English

Face au drapeau. English Michael Strogoff; Or, The Courier of the Czar

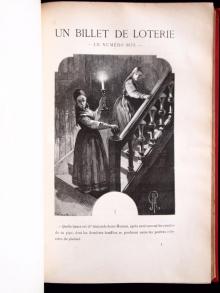

Michael Strogoff; Or, The Courier of the Czar Un billet de loterie. English

Un billet de loterie. English The Secret of the Island

The Secret of the Island Off on a Comet! a Journey through Planetary Space

Off on a Comet! a Journey through Planetary Space Into the Niger Bend: Barsac Mission, Part 1

Into the Niger Bend: Barsac Mission, Part 1 All Around the Moon

All Around the Moon A Journey to the Center of the Earth - Jules Verne: Annotated

A Journey to the Center of the Earth - Jules Verne: Annotated 20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 2

20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 2 Robur-le-Conquerant

Robur-le-Conquerant Les Index Noires

Les Index Noires Michael Strogoff; or the Courier of the Czar

Michael Strogoff; or the Courier of the Czar 20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 1

20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 1 Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Five Weeks In A Balloon

Five Weeks In A Balloon Journey to the Center of the Earth

Journey to the Center of the Earth 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday

Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday The Collected Works of Jules Verne: 36 Novels and Short Stories (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics)

The Collected Works of Jules Verne: 36 Novels and Short Stories (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics) The Survivors of the Chancellor

The Survivors of the Chancellor Their Island Home

Their Island Home Le Chateau des Carpathes

Le Chateau des Carpathes Les Cinq Cents Millions de la Begum

Les Cinq Cents Millions de la Begum The Floating Island

The Floating Island Cinq Semaines En Ballon

Cinq Semaines En Ballon Autour de la Lune

Autour de la Lune