- Home

- Jules Verne

Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday Page 16

Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday Read online

Page 16

END OF THE FIRST PART.

Part II

CHAPTER I—THE SEAL HUNT.

ALL had gone well at French Den in Gordon’s absence. Briant’s chief anxiety had been the inexplicable conduct of his brother, from whom he could still obtain no other answer than, —

‘There is nothing the matter with me.’

‘You will not tell me, Jack?’ Briant would say. ‘You are wrong! It would be a relief for you and for me! I can see you are getting more miserable and gloomier every day! I am your elder brother, and I have the right to know what is grieving you. What have you done?’

‘What have I done?’ Jack would say, as if unable to bear it any longer. You, perhaps, might forgive me, but the others—’

‘The others? the others? What are you talking about Jack?’

Jack would begin to cry, but all his brother could do only made him add, —

‘Later on you will know!’

After such a reply Briant’s anxiety may be imagined. What was there so serious that Jack could have done? At all costs he would find out if he could. As soon as Gordon came back Briant spoke to him about these half-confessions wrung from his brother, and even asked him to interfere.

‘What would be the use of that?’ asked Gordon. ‘Better leave Jack to himself. What he has done is doubtless some peccadillo, the importance of which he exaggerates. Wait till he tells you himself.’

Next morning the young colonists were all at work. And to begin with, Moko claimed attention to the state of his larder, which, notwithstanding that the snares were all set, was running low. Of large game there was none; and the boys devoted their first attention to making traps, in which they might capture vicugnas, peccaries, or guazulis, and waste no powder or shot. And during the whole month of November, answering to May in our latitudes, they were occupied in this work.

The guanaco and the vicugna and her little ones were being kept under the nearest trees tethered to long ropes, where they would get on very well till the winter, when a shelter of some sort would have to be contrived for them. This Gordon decided should be a shed with a high palisaded enclosure at the foot of Auckland Hill on the shore of the lake, a little beyond the door of the cave; and the work was at once put in hand.

A regular workshop was organized under Baxter’s directions. It was pleasant to see the boys more or less skilfully busy with the tools they had found in the carpenters chest—some with saws, some with axes, some with adzes. Although the work was at times rather irksome to them, yet they never complained. Medium-sized trees were cut down at the root had their branches cut away, and became the uprights of an enclosure large enough to hold a dozen animals in comfort. Sunk deeply in the ground and supported by cross-pieces, they were strong enough to defy the attempts of any of the animals to escape. The shed was built of the planks of the schooner, and this saved the young carpenters the trouble of cutting planks out of trees, which would have been a very difficult job under the circumstances. The roof was made of a thick tarpaulin. A good thick litter which could be often renewed, a fresh feed of grass, or moss, or leaves, and the animals required nothing else to keep them in condition. Garnett and Service, who had the management of the cattle, were rewarded for their trouble by finding the guanaco and vicugna get tamer every day. Soon there were other animals in the enclosure. First there came a second guanaco caught in one of the traps in the forest, then a couple of vicugnas, male and female, which Baxter had caught with the help of Wilcox, who was becoming quite adroit in the use of the bolas. By-and-by there was added a nandu, which Fan had captured; but it was obvious that this was as intractable as the first, notwithstanding all that Service could do.

Until the enclosure was completed the guanaco and vicugna had been put in the store-room at night The howling of jackals, yelping of foxes, and growling of other wild beasts, were too loud round French Den for it to be prudent to leave the cattle outside.

While Garnett and Service had special charge of the cattle, Wilcox and a few others were constantly occupied in preparing snares and nets, and daily visiting them. Iverson and Jenkins found plenty to do in another way. Ostriches, pheasant fowls, guinea fowls, and tinamous became so numerous that a poultry-yard became necessary, and this was railed off in a corner of the enclosure, and put under the care of the two youngsters who were most zealous in the discharge of their duties.

Moko now had at his disposal not only the milk of the vicugnas but the eggs of the feathered prisoners, and had Gordon not cautioned him to be careful of the sugar he might have launched out extensively into sweetmeats. As it was, it was only on Sundays and holidays that such efforts appeared on the table, to the very great satisfaction of Dole and Costar in particular.

As it was impossible to make sugar, could not the boys find something as a substitute? Service—Crusoe books in hand—insisted that they had only to look to find.

Gordon, therefore, sought about, and in Trap Woods he came across a group of trees which three months later, in the early days of autumn, would be covered with most beautiful purple foliage.

‘They are maples,’ he said, ‘sugar-trees.’

‘Trees of sugar!’ exclaimed Costar.

‘No, greedy,’ said Gordon. ‘I said sugar-trees, not trees of sugar; so put in your tongue.’

This was one of the most important discoveries the boys had made since their move to French Den. By making an incision in the maple-trunks Gordon obtained a liquid produced by the condensation of the sap, and this sap when solidified yielded the sugary substance. Although inferior in saccharine qualities to the juice of the cane and the beet, the substance was just as valuable for cooking purposes, and it was certainly better than the similar product from the birch in the springtime.

Moko now began to experiment with the trulca and algarrobe berries. Crushing them in a tub with a heavy lump of wood, he procured from them a liquor which was found to sweeten the hot drinks fairly well, and the leaves from the tea-tree proved to be almost as good as those of the fragrant Chinese plant, so that the boys never failed to bring some home with them when they went into the woods.

If Charman Island did not yield its inhabitants what was superfluous, it certainly gave them what was necessary. In one thing it did fail them, and that was in fresh vegetables, and they had to take refuge in the preserved vegetables, of which there had been a hundred boxes, which Gordon dealt out as economically as possible. Briant had even tried to cultivate the yams that had returned to a wild state, and which the French castaway had sown at the foot of the cliff, but his efforts were in vain. Fortunately the celery flourished abundantly on the shores of Family Lake, and there was no need to be sparing of it.

Meanwhile Donagan was constantly thinking of an expedition to South Moors on the other side of the Zealand River; but there was much danger attending this for at flood times the marshes were covered with water from both lake and sea.

Wilcox and Webb caught a number of agoutis as big as hares, whose whitish flesh, though rather dry, has a flavour between that of the rabbit and the pig. There was no running to be got out of these animals even with the assistance of Fan, but when they were found at home all that had to be done was to whistle gently at the hole and out they would come to see what was the matter. Besides the agoutis there were caught a few gluttons, and some zorillos somewhat like martens with their beautiful black fur striped with white, but giving off very fetid emanations.

‘How can they stand such a stink?’ asked Iverson.

‘Merely a matter of habit!’ said Service.

There were galaxias in the river, and there were very much larger ones in the lake, and with them were some curious trout that no matter how they were cooked had always a brackish flavour. Among the seaweed of the bay were shoals of hake, and when the time came for the salmon to come up the stream Moko would be able to lay in a good supply of fish, which, preserved in salt, would afford excellent eating during the winter.

At Gordon’s request Baxter busied himself in makin

g bows out of the pliant branches of the ash, and arrows out of reeds tipped with an iron nail. With these Wilcox and Cross, who were the best marksmen after Donagan, would be able to bring down a little feathered game. Gordon continued to do all he could to discourage the waste of ammunition, but there came an occasion on which he consented to depart from his habitual parsimony.

One day—it was the 7th of December-—Donagan had taken him apart, and said to him, —

‘We are swarming with these jackals and foxes. They come in herds at night and destroy our nets and the things we have caught in them! We really ought to stop it.’

‘Cannot we set some traps for them?’ asked Gordon, seeing what his companion was driving at.

‘Traps!’ exclaimed Donagan, who had lost none of his contempt for these vulgar engines of the chase. ‘Traps! The jackals might be stupid enough to be caught in them sometimes, but with the foxes it is quite a different thing. They are too sharp to be caught, in spite of all Wilcox can do. Some night or other oar enclosure will be devastated, and our poultry-yard stripped!’

‘Well, if it is necessary, I agree to a few dozen cartridges, but mind you are sure of your aim.’

‘All right You may depend upon that. We’ll have an ambush to-night on the track of these beasts, and will have such a massacre that they won’t trouble us again for some time.’

The matter was urgent The foxes of these regions seemed to be much more cunning than those of other nations, almost as cunning in fact as those of South America, where the haciendas are constantly being ravaged by them.

At eleven o’clock that night, Donagan, Briant Wilcox, Baxter, Webb, Cross, and Service took up their position in a covert by the side of the lake and near Trap Woods.

Fan had not been invited; she would probably have done harm by giving the alarm, and, besides, no finding by scent was required.

The night was very dark.

A deep silence, untroubled by the slightest breath of breeze, allowed even the gliding of the foxes over the dry herbage to be heard. A little after midnight Donagan announced the approach of a troop on their way through the covert to drink in the lake. The boys waited impatiently, while the animals, to the number of twenty or more, collected by the waterside, which they did slowly and cautiously, as if they had some suspicion of an ambush. Suddenly, at a signal from Donagan, there was a straggling volley. Five or six foxes rolled on to the ground, and the others, most of them mortally wounded, fled right and left.

When day came, a dozen foxes were found dead in the covert. And as the massacre was continued on three successive nights the little colony was soon delivered from the dangerous visits that imperilled the poultry-yard, and fifty fine silver-grey skins, some as carpets, some as garments, added to the comfort of French Den.

On the 15th of December there was a grand expedition to the bay. The weather was fine, and Gordon decided that all should go—very much to the satisfaction of the youngsters who were loud in their demonstrations of delight.

The expedition had for its chief object a hunt of the seals that frequented Wreck Coast. During the long nights of the long winter the means of lighting had been almost exhausted; of the candles made by Baudoin only two or three dozen remained; the oil in the schooner’s barrels had also almost gone, and this had made Gordon anxious.

It is true that Moko had put by a certain quantity of the fat from the birds and beasts he had cooked, but this would soon be used up. Was it not possible to replace this by a substance that nature furnished ready prepared, or nearly so; in default of vegetable oil, could the little colony obtain a stock of oil from animals?

Certainly this could be done, if the boys could manage to kill a certain number of seals, those furred otaries who came to disport themselves on the reefs of Schooner Bay during the warm season. But the boys would have to make haste, for the amphibians would soon be off to the more southerly regions of the Antarctic Ocean.

The projected expedition was thus of great importance, and preparations were made in such a manner as to give the best results.

For some time Service and Garnett had been occupied, not without success, in breaking in the two guanacos as beasts of burden. Baxter had made a halter of plaited grass covered with sail-cloth, and if the guanacos could not yet be mounted, they might at least be harnessed to the chariot, and that would be better than for the boys to have to drag it along.

On the day of the expedition the chariot was loaded with stores, provisions, and utensils, among the last being a large vat, and half-a-dozen empty barrels, which were to be brought back full of seal oil, it being better to cut up the seals on the spot than to bring them to French Den, and fill the air with the unhealthy stench.

The departure took place at sunrise, and for two hours there was no obstacle on the road. If the chariot did not go very fast it was because the uneven ground along the bank of Zealand River lent itself imperfectly to traction by guanacos. But where difficulty arose was when the little troop skirted the swamp of Bog Woods, and entered the forest Dole and Costar then complained of being tired, and Gordon, at Briant’s request, allowed them to get on to the chariot, so as to have a rest as they went.

About eight o’clock, while the team was laboriously advancing by the edge of the swamp, the shouts of Webb and Cross, who were a little in front, brought up first Donagan, and then the rest.

About a hundred yards away, in the mud of Bog Woods, there wallowed an enormous animal, which Donagan recognized at once. It was a hippopotamus, fat and rosy, which—happily for it—disappeared under the thick underwood of the marsh before it was possible to fire. Though what would have been the good of firing so uselessly?

‘What is that big beast?’ asked Dole

‘It is a hippopotamus,’ said Gordon.

‘A hippopotamus! What a strange name.’

‘That is to say, a river-horse,’ said Briant.

‘But it is not like a horse,’ said Costar.

‘No,’ said Service, ‘I fancy it ought to have been called a piggobottomus.’

The suggestion was not unreasonable, and caused a shout of laughter from the youngsters.

It was a little after ten o’clock before Gordon reached the beach at Schooner Bay. A halt was made near the river-bank, where the camp had been pitched during the demolition of the yacht.

There were about a hundred seals gambolling among the rocks, or basking in the sun; there were even some disporting themselves on the sand beyond the cordon of reefs.

These amphibians were evidently little familiar with the presence of man. Perhaps they had never seen a human being, for the Frenchman had been dead for twenty years; and although it is a measure of ordinary prudence, among those hunted in the Arctic or Antarctic seas, for the oldest of the band to stand sentinel, there was no such precaution here. But it was desirable not to alarm them, for in a few moments they might all clear away.

When they first emerged into the bay, the young colonists had looked out towards the wide horizon between American Cape and False Point.

The sea was quite deserted. Again it was clear enough that the island was not on any of the maritime highways.

It might happen, however, that a ship would pass within sight of the island, and in that case an observatory on the top of Auckland Hill, or False Point would be better than the existing signal-mast for the purpose of attracting attention. But some one would have to be on guard there night and day, far away from the caves, and the suggestion was dismissed as impracticable. Briant who was always thinking of getting back to New Zealand, could not but agree. It was, indeed, a pity that French Den was not situated on the bay side of Auckland Hill.

After a hasty lunch, Gordon, Briant Donagan, Cross, Baxter, Webb, Wilcox, Garnett and Service prepared themselves for the seal-hunt While this was about Iverson, Jenkins, Jack, Dole, and Costar were to remain at the camp in charge of Moko, and as it was not advisable to let Fan loose among the amphibious herd, the dog was left to keep them company. They could amuse thems

elves by looking after the two guanacos put out to graze under the trees.

All the firearms in the colony, rifles and revolvers, had been brought out with sufficient ammunition, which Gordon did not begrudge this time, as it was for the general good.

To cut off the retreat of the seals to the sea was the first thing to be done. Donagan, by general consent, led the way down the river to its mouth, keeping under shelter of the bank as he went. That done, it was easy to get out along the reefs in such a manner as to get in the rear of the seals.

This plan was executed with much care. The boys, from thirty to forty yards behind each other, had soon formed a half-circle between the beach and the sea. Then at a signal from Donagan, they all fired; the guns rang out together, and every gun had its victim.

The seals that had not been hit stood up, wagged their tails and their fins. Then, frightened by the noise, they rushed in a bound towards the reefs. They were pursued with the revolvers. Donagan was in his element, and did wonders, while his comrades followed his example to the best of their ability.

The massacre lasted but a few minutes, until the seals had been tracked beyond the edge of the reef, where the survivors disappeared, leaving twenty killed or wounded behind.

The expedition had succeeded, and the hunters returned to the camp. The afternoon was spent in a task which was as repugnant as it could be. Gordon himself took part in it; and as the work was indispensable, all hands went through with it resolutely. First, the seals killed among the reefs had to be dragged on the beach, and although these were but of medium size they gave a good deal of trouble.

While this was in hand Moko had set the big basin on the fire between two large stones, and put water into it. The quarters of seal, cut into five or six pieces each, were then placed in the basin, and a few minutes afterwards they were on the boil, with the clear oil oozing from them, and floating to the surface of the water, from which it was skimmed on into the casks. The place was rendered almost untenable by the disgusting odour which this caused. The boys held their noses, but they did not shut their ears, and many were the jokes about the disagreeable occupation, from which even the delicate Lord Donagan did not budge, and which was resumed next morning.

Michael Strogoff; Or the Courier of the Czar: A Literary Classic

Michael Strogoff; Or the Courier of the Czar: A Literary Classic Voyage au centre de la terre. English

Voyage au centre de la terre. English Journey Through the Impossible

Journey Through the Impossible The Castaways of the Flag

The Castaways of the Flag L'île mystérieuse. English

L'île mystérieuse. English Maître du monde. English

Maître du monde. English Around the World in Eighty Days

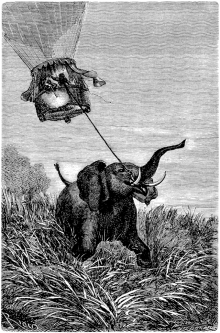

Around the World in Eighty Days A Voyage in a Balloon

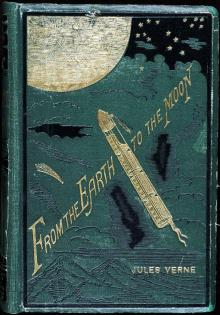

A Voyage in a Balloon From the Earth to the Moon, Direct in Ninety-Seven Hours and Twenty Minutes: and a Trip Round It

From the Earth to the Moon, Direct in Ninety-Seven Hours and Twenty Minutes: and a Trip Round It Paris in the Twentieth Century

Paris in the Twentieth Century City in the Sahara - Barsac Mission 02

City in the Sahara - Barsac Mission 02 The English at the North Pole

The English at the North Pole The Field of Ice

The Field of Ice From the Earth to the Moon

From the Earth to the Moon Un capitaine de quinze ans. English

Un capitaine de quinze ans. English The Mysterious Island

The Mysterious Island Les indes-noirs. English

Les indes-noirs. English Robur-le-conquerant. English

Robur-le-conquerant. English Propeller Island

Propeller Island Around the World in Eighty Days. Junior Deluxe Edition

Around the World in Eighty Days. Junior Deluxe Edition Les forceurs de blocus. English

Les forceurs de blocus. English In the Year 2889

In the Year 2889 Journey to the Centre of the Earth

Journey to the Centre of the Earth Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea From the Earth to the Moon; and, Round the Moon

From the Earth to the Moon; and, Round the Moon Vingt mille lieues sous les mers. English

Vingt mille lieues sous les mers. English Cinq semaines en ballon. English

Cinq semaines en ballon. English Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas

Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas Face au drapeau. English

Face au drapeau. English Michael Strogoff; Or, The Courier of the Czar

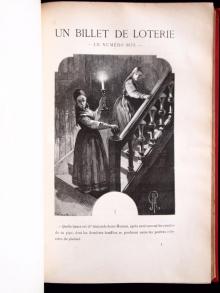

Michael Strogoff; Or, The Courier of the Czar Un billet de loterie. English

Un billet de loterie. English The Secret of the Island

The Secret of the Island Off on a Comet! a Journey through Planetary Space

Off on a Comet! a Journey through Planetary Space Into the Niger Bend: Barsac Mission, Part 1

Into the Niger Bend: Barsac Mission, Part 1 All Around the Moon

All Around the Moon A Journey to the Center of the Earth - Jules Verne: Annotated

A Journey to the Center of the Earth - Jules Verne: Annotated 20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 2

20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 2 Robur-le-Conquerant

Robur-le-Conquerant Les Index Noires

Les Index Noires Michael Strogoff; or the Courier of the Czar

Michael Strogoff; or the Courier of the Czar 20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 1

20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 1 Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Five Weeks In A Balloon

Five Weeks In A Balloon Journey to the Center of the Earth

Journey to the Center of the Earth 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday

Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday The Collected Works of Jules Verne: 36 Novels and Short Stories (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics)

The Collected Works of Jules Verne: 36 Novels and Short Stories (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics) The Survivors of the Chancellor

The Survivors of the Chancellor Their Island Home

Their Island Home Le Chateau des Carpathes

Le Chateau des Carpathes Les Cinq Cents Millions de la Begum

Les Cinq Cents Millions de la Begum The Floating Island

The Floating Island Cinq Semaines En Ballon

Cinq Semaines En Ballon Autour de la Lune

Autour de la Lune