- Home

- Jules Verne

Un capitaine de quinze ans. English Page 19

Un capitaine de quinze ans. English Read online

Page 19

CHAPTER XVIII.

A TERRIBLE DISCOVERY.

The morning of the 18th dawned, the day on which, according to Harris'sprediction, the travellers were to be safely housed at San Felice. Mrs.Weldon was really much relieved at the prospect, for she was aware thather strength must prove inadequate to the strain of a more protractedjourney. The condition of her little boy, who was alternately flushedwith fever, and pale with exhaustion, had begun to cause her greatanxiety, and unwilling to resign the care of the child even to Nan hisfaithful nurse, she insisted upon carrying him in her own arms. Twelvedays and nights, passed in the open air, had done much to try herpowers of endurance, and the charge of a sick child in addition wouldsoon break down her strength entirely.

Dick Sands, Nan, and the negroes had all borne the march very fairly.Their stock of provisions, though of course considerably diminished,was still far from small. As for Harris, he had shown himselfpre-eminently adapted for forest-life, and capable of bearing anyamount of fatigue. Yet, strange to say, as he approached the end of thejourney, his manner underwent a remarkable change; instead ofconversing in his ordinary frank and easy way, he became silent andpreoccupied, as if engrossed in his own thoughts. Perhaps he had aninstinctive consciousness that "his young friend," as he was in thehabit of addressing Dick, was entertaining hard suspicions about him.

The march was resumed. The trees once again ceased to be crowded inimpenetrable masses, but stood in clusters at considerable distancesapart. Now, Dick tried to argue with himself, they must be coming tothe true pampas, or the man must be designedly misleading them; and yetwhat motive could he have?

Although during the earlier part of the day there occurred nothing thatcould be said absolutely to justify Dick's increasing uneasiness, twocircumstances transpired which did not escape his observation, andwhich, he felt, might be significant. The first of these was a suddenchange in Dingo's behaviour. The dog, throughout the march, haduniformly run along with his nose upon the ground, smelling the grassand shrubs, and occasionally uttering a sad low whine; but to-day heseemed all agitation; he scampered about with bristling coat, with hishead erect, and ever and again burst into one of those furious fits ofbarking, with which he had formerly been accustomed to greet Negoro'sappearance upon the deck of the "Pilgrim."

The idea that flitted across Dick's mind was shared by Tom.

"Look, Mr. Dick, look at Dingo; he is at his old ways again," said he;"it is just as if Negoro...."

"Hush!" said Dick to the old man, who continued in a lower voice,--

"It is just as if Negoro had followed us; do you think it is likely?"

"It might perhaps be to his advantage to follow us, if he doesn't knowthe country; but if he does know the country, why then...."

Dick did not finish his sentence, but whistled to Dingo. The dogreluctantly obeyed the call.

As soon as the dog was at his side, Dick patted him, repeating,--

"Good dog! good Dingo! where's Negoro?"

The sound of Negoro's name had its usual effect; it seemed to irritatethe animal exceedingly, and he barked furiously, and apparently wantedto dash into the thicket.

Harris had been an interested spectator of the scene, and nowapproached with a peculiar expression on his countenance, and inquiredwhat they were saying to Dingo.

"Oh, nothing much," replied Tom; "we were only asking him for news of alost acquaintance."

"Ah, I suppose you mean that Portuguese cook of yours."

"Yes," answered Tom; "we fancied from Dingo's behaviour, that Negoromust be somewhere close at hand."

"Why don't you send and search the underwood? perhaps the poor wretchis in distress."

"No need of that, Mr. Harris; Negoro, I have no doubt, is quite capableof taking care of himself."

"Well, just as you please, my young friend," said Harris, with an airof indifference.

Dick turned away; he continued his endeavours to pacify Dingo, and theconversation dropped.

The other thing that had arrested Dick's attention was the behaviour ofthe horse. If they had been as near the hacienda as Harris described,would not the animal have pricked up its ears, sniffed the air, andwith dilated nostril, exhibited some sign of satisfaction, as beingupon familiar ground?

But nothing of the kind was to be observed; the horse plodded along asunconcernedly as if a stable were as far away as ever.

Even Mrs. Weldon was not so engrossed with her child, but what she wasfain to express her wonder at the deserted aspect of the country. Notrace of a farm-labourer was anywhere to be seen! She cast her eye atHarris, who was in his usual place in front, and observing how he waslooking first to the left, and then to the right, with the air of a manwho was uncertain of his path, she asked herself whether it waspossible their guide might have lost his way. She dared not entertainthe idea, and averted her eyes, that she might not be harassed by hismovements.

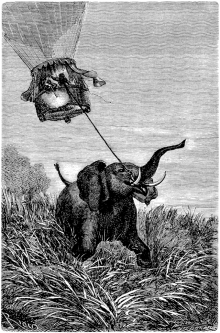

After crossing an open plain about a mile in width, the travellers onceagain entered the forest, which resumed something of the same densenessthat had characterized it farther to the west. In the course of theafternoon, they came to a spot which was marked very distinctly by thevestiges of some enormous animals, which must have passed quiterecently. As Dick looked carefully about him, he observed that thebranches were all torn off or broken to a considerable height, and thatthe foot-tracks in the trampled grass were much too large to be thoseeither of jaguars or panthers. Even if it were possible that the printson the ground had been made by ais or other taidigrades, this wouldfail to account in the least for the trees being broken to such aheight. Elephants alone were capable of working such destruction in theunderwood, but elephants were unknown in America. Dick was puzzled, butcontrolled himself so that he would not apply to Harris for anyenlightenment; his intuition made him aware that a man who had oncetried to make him believe that giraffes were ostriches, would nothesitate a second time to impose upon his credulity.

More than ever was Dick becoming convinced that Harris was a traitor,and he was secretly prompted to tax him with his treachery. Still hewas obliged to own that he could not assign any motive for the manacting in such a manner with the survivors of the "Pilgrim," andconsequently hesitated before he actually condemned him for conduct sobase and heartless. What could be done? he repeatedly asked himself. Onboard ship the boy captain might perchance have been able to devisesome plan for the safety of those so strangely committed to his charge,but here on an unknown shore, he could only suffer from the burden ofthis responsibility the more, because he was so utterly powerless toact.

He made up his mind on one point. He determined not to alarm the pooranxious mother a moment before he was actually compelled. It was hiscarrying out this determination that explained why on subsequentlyarriving at a considerable stream, where he saw some huge heads,swollen muzzles, long tusks and unwieldy bodies rising from amidst therank wet grass, he uttered no word and gave no gesture of surprise; butonly too well he knew, at a glance, that he must be looking at a herdof hippopotamuses.

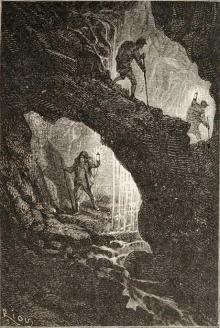

"Look here! here are hands, men's hands."]

It was a weary march that day; a general feeling of depression spreadinvoluntarily from one to another; hardly conscious to herself of herweariness, Mrs. Weldon was exhibiting manifest symptoms of lassitude;and it was only Dick's moral energy and sense of duty that kept himfrom succumbing to the prevailing dejection.

About four o'clock, Tom noticed something lying in the grass, andstooping down he picked up a kind of knife; it was of peculiar shape,being very wide and flat in the blade, while its handle, which was ofivory, was ornamented with a good deal of clumsy carving. He carried itat once to Dick, who, when he had scrutinized it, held it up to Harris,with the remark,--

"There must be natives not far off."

"Quite right, my young friend; the hacienda must be a very few milesaway,--but yet, but yet...."

He hesitated.

"You don't mean that you are not sure of your way," said Dick sharply.

"Not exactly tha

t," replied Harris; "yet in taking this short cutacross the forest, I am inclined to think I am a mile or so out of theway. Perhaps I had better walk on a little way, and look about me."

"No; you do not leave us here," cried Dick firmly.

"Not against your will; but remember, I do not undertake to guide youin the dark."

"We must spare you the necessity for that. I can answer for it thatMrs. Weldon will raise no objection to spending another night in theopen air. We can start off to-morrow morning as early as we like, andif the distance be only what you represent, a few hours will easilyaccomplish it."

"As you please," answered Harris with cold civility.

Just then, Dingo again burst out into a vehement fit of barking, and itrequired no small amount of coaxing on Dick's part to make him ceasefrom his noise.

It was decided that the halt should be made at once. Mrs. Weldon, as ithad been anticipated, urged nothing against it, being preoccupied byher immediate attentions to Jack, who was lying in her arms, sufferingfrom a decided attack of fever. The shelter of a large thicket had justbeen selected by Dick as a suitable resting-place for the night, whenTom, who was assisting in the necessary preparations, suddenly gave acry of horror.

"What is it, Tom?" asked Dick very calmly.

"Look! look at these trees! they are spattered with blood! and lookhere! here are hands, men's hands, cut off and lying on the ground!"

"What?" cried Dick, and in an instant was at his side.

His presence of mind did not fail him; he whispered,--

"Hush! Tom! hush! not a word!"

But it was with a shudder that ran through his veins that he witnessedfor himself the mutilated fragments of several human bodies, and saw,lying beside them, some broken forks, and some bits of iron chain.

The sight of the gory remains made Dingo bark ferociously, and Dick,who was most anxious that Mrs. Weldon's attention should not be calledto the discovery, had the greatest difficulty in driving him back; butfortunately the lady's mind was so engrossed with her patient, that shedid not observe the commotion. Harris stood aloof; there was no one tonotice the change that passed over his countenance, but the expressionwas almost diabolical in its malignity.

Poor old Tom himself seemed perfectly spell-bound. With his handsclenched, his eyes dilated, and his breast heaving with emotion, hekept repeating without anything like coherence, the words,--

"Forks! chains! forks! ... long ago ... remember ... too well ...chains!"

"For Mrs. Weldon's sake, Tom, hold your tongue!" Dick implored him.

Tom, however, was full with some remembrance of the past; he continuedto repeat,--

"Long ago ... forks ... chains!" until Dick led him out of hearing.

A fresh halting-place was chosen a short distance further on, andsupper was prepared. But the meal was left almost untasted; not so muchthat hunger had been overcome by fatigue, but because the indefinablefeeling of uneasiness, that had taken possession of them all, hadentirely destroyed all appetite.

The man was gone, and his horse with him.]

Gradually the night became very dark. The sky was covered with heavystorm-clouds, and on the western horizon flashes of summer lightningnow and then glimmered through the trees. The air was perfectly still;not a leaf stirred, and the atmosphere seemed so charged withelectricity as to be incapable of transmitting sound of any kind.

Dick, himself, with Austin and Bat in attendance, remained on guard,all of them eagerly straining both eye and ear to catch any light orsound that might disturb the silence and obscurity. Old Tom, with hishead sunk upon his breast, sat motionless, as in a trance; he wasgloomily revolving the awakened memories of the past. Mrs. Weldon wasengaged with her sick child. Scarcely one of the party was reallyasleep, except indeed it might be Cousin Benedict, whose reasoningfaculties were not of an order to carry him forwards into any futurecontingencies.

Midnight was still an hour in advance, when the dull air seemed filledwith a deep and prolonged roar, mingled with a peculiar kind ofvibration.

Tom started to his feet. A fresh recollection of his early days hadstruck him.

"A lion! a lion!" he shouted.

In vain Dick tried to repress him; but he repeated,--

"A lion! a lion!"

Dick Sands seized his cutlass, and, unable any longer to control hiswrath, he rushed to the spot where he had left Harris lying.

The man was gone, and his horse with him!

All the suspicions that had been so long pent up within Dick's mind nowshaped themselves into actual reality. A flood of light had broken inupon him. Now he was convinced, only too certainly, that it was not thecoast of America at all upon which the schooner had been cast ashore!it was not Easter Island that had been sighted far away in the west!the compass had completely deceived him; he was satisfied now that thestrong currents had carried them quite round Cape Horn, and that theyhad really entered the Atlantic. No wonder that quinquinas, caoutchouc,and other South American products, had failed to be seen. This wasneither the Bolivian pampas nor the plateau of Atacama. They weregiraffes, not ostriches, that had vanished down the glade; they wereelephants that had trodden down the underwood; they were hippopotamusesthat were lurking by the river; it was indeed the dreaded tzetsy thatCousin Benedict had so triumphantly discovered; and, last of all, itwas a lion's roar that had disturbed the silence of the forest. Thatchain, that knife, those forks, were unquestionably the instruments ofslave-dealers; and what could those mutilated hands be, except therelics of their ill-fated victims?

Harris and Negoro must be in a conspiracy!

It was with terrible anguish that Dick gnashed his teeth and muttered,--

"Yes, it is too true; we are in Africa! in equatorial Africa! in theland of slavery! in the very haunt of slave-drivers!"

END OF FIRST PART.

*****

Michael Strogoff; Or the Courier of the Czar: A Literary Classic

Michael Strogoff; Or the Courier of the Czar: A Literary Classic Voyage au centre de la terre. English

Voyage au centre de la terre. English Journey Through the Impossible

Journey Through the Impossible The Castaways of the Flag

The Castaways of the Flag L'île mystérieuse. English

L'île mystérieuse. English Maître du monde. English

Maître du monde. English Around the World in Eighty Days

Around the World in Eighty Days A Voyage in a Balloon

A Voyage in a Balloon From the Earth to the Moon, Direct in Ninety-Seven Hours and Twenty Minutes: and a Trip Round It

From the Earth to the Moon, Direct in Ninety-Seven Hours and Twenty Minutes: and a Trip Round It Paris in the Twentieth Century

Paris in the Twentieth Century City in the Sahara - Barsac Mission 02

City in the Sahara - Barsac Mission 02 The English at the North Pole

The English at the North Pole The Field of Ice

The Field of Ice From the Earth to the Moon

From the Earth to the Moon Un capitaine de quinze ans. English

Un capitaine de quinze ans. English The Mysterious Island

The Mysterious Island Les indes-noirs. English

Les indes-noirs. English Robur-le-conquerant. English

Robur-le-conquerant. English Propeller Island

Propeller Island Around the World in Eighty Days. Junior Deluxe Edition

Around the World in Eighty Days. Junior Deluxe Edition Les forceurs de blocus. English

Les forceurs de blocus. English In the Year 2889

In the Year 2889 Journey to the Centre of the Earth

Journey to the Centre of the Earth Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea From the Earth to the Moon; and, Round the Moon

From the Earth to the Moon; and, Round the Moon Vingt mille lieues sous les mers. English

Vingt mille lieues sous les mers. English Cinq semaines en ballon. English

Cinq semaines en ballon. English Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas

Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas Face au drapeau. English

Face au drapeau. English Michael Strogoff; Or, The Courier of the Czar

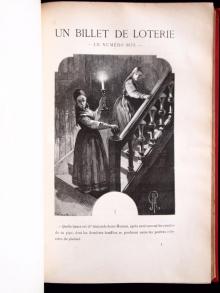

Michael Strogoff; Or, The Courier of the Czar Un billet de loterie. English

Un billet de loterie. English The Secret of the Island

The Secret of the Island Off on a Comet! a Journey through Planetary Space

Off on a Comet! a Journey through Planetary Space Into the Niger Bend: Barsac Mission, Part 1

Into the Niger Bend: Barsac Mission, Part 1 All Around the Moon

All Around the Moon A Journey to the Center of the Earth - Jules Verne: Annotated

A Journey to the Center of the Earth - Jules Verne: Annotated 20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 2

20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 2 Robur-le-Conquerant

Robur-le-Conquerant Les Index Noires

Les Index Noires Michael Strogoff; or the Courier of the Czar

Michael Strogoff; or the Courier of the Czar 20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 1

20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 1 Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Five Weeks In A Balloon

Five Weeks In A Balloon Journey to the Center of the Earth

Journey to the Center of the Earth 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday

Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday The Collected Works of Jules Verne: 36 Novels and Short Stories (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics)

The Collected Works of Jules Verne: 36 Novels and Short Stories (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics) The Survivors of the Chancellor

The Survivors of the Chancellor Their Island Home

Their Island Home Le Chateau des Carpathes

Le Chateau des Carpathes Les Cinq Cents Millions de la Begum

Les Cinq Cents Millions de la Begum The Floating Island

The Floating Island Cinq Semaines En Ballon

Cinq Semaines En Ballon Autour de la Lune

Autour de la Lune