- Home

- Jules Verne

Michael Strogoff; or the Courier of the Czar Page 2

Michael Strogoff; or the Courier of the Czar Read online

Page 2

“And, naturally, you made it ‘radiant,’ in the columns of the Daily Telegraph.”

“Exactly.”

“Do you remember, Mr. Blount, what occurred at Zakret in 1812?”

“I remember it as well as if I had been there, sir,” replied the English correspondent.

“Then,” continued Alcide Jolivet, “you know that, in the middle of a fête given in his honour, it was announced to the Emperor Alexander that Napoleon had just crossed the Niemen with the vanguard of the French army. Nevertheless the Emperor did not leave the fête, and notwithstanding the extreme gravity of intelligence which might cost him his empire, he did not allow himself to show more uneasiness. . . .”

“Than our host exhibited when General Kissoff informed him that the telegraphic wires had just been cut between the frontier and the government of Irkutsk.”

“Ah! you are aware of that?”

“I am!”

“As regards myself, it would be difficult to avoid knowing it, since my last telegram reached Udinsk,” observed Alcide Jolivet, with some satisfaction.

“And mine only as far as Krasnoiarsk,” answered Harry Blount, in a no less satisfied tone.

“Then you know also that orders have been sent to the troops of Nikolaevsk?”

“I do, sir; and at the same time a telegram was sent to the Cossacks of the government of Tobolsk to concentrate their forces.”

“Nothing can be more true, Mr. Blount; I was equally well acquainted with these measures, and you may be sure that my dear cousin shall know something of them tomorrow”

“Exactly as the readers of the Daily Telegraph shall know it also, M. Jolivet”

“Well, when one sees all that is going on. . . .”

“And when one hears all that is said. . . .”

“An interesting campaign to follow, Mr. Blount”

“I shall follow it, M. Jolivet!”

“Then it is possible that we shall find ourselves on ground less safe, perhaps, than the floor of this ball-room.”

“Less safe, certainly, but——”

“But much less slippery,” added Alcide Jolivet, holding up his companion, just as the latter, drawing back, was about to lose his equilibrium.

Thereupon the two correspondents separated, pleased enough to know that the one had not stolen a march on the other.

At that moment the doors of the rooms adjoining the great reception saloon were thrown open, disclosing to view several immense tables beautifully laid out, and groaning under a profusion of valuable china and gold plate. On the central table, reserved for the princes, princesses, and members of the corps diplomatique, glittered an épergne of inestimable price, brought from London, and around this chef-d’œuvre of chased gold, were reflected, under the light of the lustres, a thousand pieces of the most beautiful service which the manufactories of Sèvres had ever produced.

The guests of the New Palace immediately began to stream towards the supper-rooms.

At that moment, General Kissoff, who had just re-entered, quickly approached the officer of chasseurs.

“Well?” asked the latter abruptly, as he had done the former time.

“Telegrams pass Tomsk no longer, sire.”

“A courier this moment!”

The officer left the hall and entered a large antechamber adjoining.

It was a cabinet with plain oak furniture, and situated in an angle of the New Palace. Several pictures, amongst others some by Horace Vernet, hung on the wall.

The officer hastily opened a window, as if he felt the want of air, and stepped out on a balcony to breathe the pure atmosphere of a lovely July night.

Beneath his eyes, bathed in moonlight, lay a fortified inclosure, from which rose two cathedrals, three palaces, and an arsenal. Around this inclosure could be seen three distinct towns: Kitai-Gorod, Beloi-Gorod, Zemlianai-Gorod—European, Tartar, or Chinese quarters of great extent, commanded by towers, belfries, minarets, and the cupolas of three hundred churches, with green domes, surmounted by the silver cross. A little winding river here and there reflected the rays of the moon. All this together formed a curious mosaic of variously coloured houses, set in an immense frame of ten leagues in circumference.

This river was the Moskowa; the town Moscow; the fortified inclosure the Kremlin; and the officer of chasseurs of the guard, who, with folded arms and thoughtful brow, was listening dreamily to the sounds floating from the New Palace over the old Muscovite city, was the Czar.

CHAPTER II.

RUSSIANS AND TARTARS.

THE Czar had not so suddenly left the ball-room of the New Palace, when the fête he was giving to the civil and military authorities and principal people of Moscow was at the height of its brilliancy, without ample cause; for he had just received information that serious events were taking place beyond the frontiers of the Ural. It had become evident that a formidable rebellion threatened to wrest the Siberian provinces from the Russian crown.

Asiatic Russia, or Siberia, covers a superficial area of 1,790,208 square miles, and contains nearly two millions of inhabitants. Extending from the Ural Mountains, which separate it from Russia in Europe, to the shores of the Pacific Ocean, it is bounded on the south by Turkestan and the Chinese Empire; on the north by the Arctic Ocean, from the Sea of Kara to Behring’s Straits. It is divided into several governments or provinces, those of Tobolsk. Yeniseisk, Irkutsk, Omsk, and Yakutsk; contains two districts, Okhotsk and Kamtschatka; and possesses two countries, now under the Muscovite dominion—that of the Kirghiz and that of the Tshouktshes. This immense extent of steppes, which includes more than one hundred and ten degrees from west to east, is a land to which both criminals are transported and political offenders are banished.

Two governor-generals represent the supreme authority of the Czar over this vast country. One resides at Irkutsk, the capital of Western Siberia. The River Tchouna, a tributary of the Yenisei, separates the two Siberias.

No rail yet furrows these wide plains, some of which are in reality extremely fertile. No iron ways lead from those precious mines which make the Siberian soil far richer below than above its surface. The traveller journeys in summer in a kibick or telga; in winter, in a sledge.

An electric telegraph, with a single wire more than eight thousand versts * in length, alone affords communication between the western and eastern frontiers of Siberia. On issuing from the Ural, it passes through Ekaterenburg, Kasimov, Tioumen, Ishim, Omsk, Elamsk, Kalyvan, Tomsk, Krasnoiarsk, Nijni-Udinsk, Irkutsk, Verkne-Nertsckink, Strelink, Albazine, Blagowstenks, Radde, Orlomskaya, Alexandrowskoë, and Nikolaevsk; and six roubles † and nineteen copecks are paid for every word sent from one end to the other. From Irkutsk there is a branch to Kiatka, on the Mongolian frontier; and from thence, for thirty copecks a word, the post conveys the despatches to Pekin in a fortnight.

It was this wire, extending from Ekaterenburg to Nikolaevsk, which had been cut, first beyond Tomsk, and then between Tomsk and Kalyvan.

This was the reason why the Czar, to the communication made to him for the second time by General Kissoff, had only answered by the words, “A courier this moment!”

The Czar had remained motionless at the window for a few moments, when the door was again opened. The chief of police appeared on the threshold.

“Enter, General,” said the Czar briefly, “and tell me all you know of Ivan Ogareff.”

“He is an extremely dangerous man, sir,” replied the chief of police.

“He ranked as colonel, did he not?”

“Yes, sire.”

“Was he an intelligent officer?”

“Very intelligent, but a man whose spirit it was impossible to subdue; and possessing an ambition which stopped at nothing, he soon became involved in secret intrigues, and it was then that he was degraded from his rank by his Highness the Grand Duke, and exiled to Siberia.”

“How long ago was that?”

“Two years since. Pardoned after six months of exile by your majesty�

��s favour, he returned to Russia.”

“And since that time, has he not revisited Siberia?”

“Yes, sire; but he voluntarily returned there,” replied the chief of police, adding, and slightly lowering his voice, “there was a time, sire, when none returned from Siberia.”

“Well, whilst I live, Siberia is and-shall be a country whence men can return.”

The Czar had the right to utter these words with some pride, for often, by his clemency, he had shown that Russian justice knew how to pardon.

The head of the police did not reply to this observation, but it was evident that he did not approve of such half-measures. According to his idea, a man who had once passed the Ural Mountains in charge of policemen, ought never again to cross them. Now, it was not thus under the new reign, and the chief of police sincerely deplored it What! No banishment for life for other crimes than those against social order! What! political exiles returning from Tobolsk, from Yakutsk, from Irkutsk! In truth, the chief of police, accustomed to the despotic sentences of the ukase which formerly never pardoned, could not understand this mode of governing. But he was silent, waiting until the Czar should interrogate him further.

The questions were not long in coming.

“Did not Ivan Ogareff,” asked the Czar, “return to Russia a second time, after that journey through the Siberian provinces, the object of which remains unknown?”

“He did.”

“And have the police lost trace of him since?”

“No, sire; for an offender only becomes really dangerous from the day he has received his pardon.”

The Czar frowned. Perhaps the chief of police feared that he had gone rather too far, though the stubbornness of his ideas was at least equal to the boundless devotion he felt for his master. But the Czar, disdaining to reply to these indirect reproaches cast on his interior policy, continued his series of questions.

“Where was Ivan Ogareff last heard of?”

“In the province of Perm.”

“In what town?”

“At Perm itself.”

“What was he doing?”

“He appeared unoccupied, and there was nothing suspicious in his conduct”

“Then he was not under the surveillance of the secret police?”

“No, sire.”

“When did he leave Perm?”

“About the month of March?”

“To go . . . ?”

“Where, is unknown.”

“And since that time, it is not known what has become of him?”

“No, sire; it is not known.”

“Well, then, I myself know,” answered the Czar. “I have received anonymous communications which did not pass through the police department; and, in the face of events now taking place beyond the frontier, I have every reason to believe that they are correct.”

“Do you mean, sire,” cried the chief of police, “that Ivan Ogareff has a hand in this Tartar rebellion?”

“Indeed I do; and I will now tell you something which you are ignorant of. After leaving Perm, Ivan Ogareff crossed the Ural mountains, entered Siberia, and penetrated the Kirghiz steppes, and there endeavoured, not without success, to foment rebellion amongst their nomadic population. He then went so far south as free Turkestan; there, in the provinces of Bokhara, Khokhand, and Koondooz, he found chiefs willing to pour their Tartar hordes into Siberia, and excite a general rising in Asiatic Russia. ‘The storm has been silently gathering, but it has at last burst like a thunder-clap, and now all means of communication between Eastern and Western Siberia have been stopped. Moreover, Ivan Ogareff, thirsting for vengeance, aims at the life of my brother!”

The Czar had become excited whilst speaking, and now paced up and down with hurried steps. The chief of police said nothing, but he thought to himself that, during the time when the emperors of Russia never pardoned an exile, schemes such as those of Ivan Ogareff could never have been realized. A few moments passed, during which he was silent, then approaching the Czar, who had thrown himself into an armchair.

“Your majesty,” said he, “has of course given orders that this rebellion may be suppressed as soon as possible?”

“Yes,” answered the Czar. “The last telegram which was able to reach Nijni-Udinsk would set in motion the troops in the governments of Yenisei, Irkutsk, Yakutsk, as well as those in the provinces of the Amoor and Lake Baikal. At the same time, the regiments from Perm and Nijni-Novgorod, and the Cossacks from the frontier, are advancing by forced marches towards the Ural Mountains; but, unfortunately, some weeks must pass before they can attack the Tartars.”

“And your majesty’s brother, his Highness the Grand Duke, is now isolated in the government of Irkutsk, and is no longer in direct communication with Moscow?”

“That is so.”

“But by the last despatches, he must know what measures have been taken by your majesty, and what help he may expect from the governments nearest to that of Irkutsk?”

“He knows that,” answered the Czar; “but what he does not know is, that Ivan Ogareff, as well as being a rebel, is also playing the part of a traitor, and that in him he has a personal and bitter enemy. It is to the Grand Duke that Ivan Ogareff owes his first disgrace; and what is more serious is, that this man is not known to him. Ivan Ogareff’s plan, therefore, is to go to Irkutsk, and, under an assumed name, offer his services to the Grand Duke. Then, after gaining his confidence, when the Tartars have invested Irkutsk, he will betray the town, and with it my brother, whose life is directly threatened. This is what I have learned from my secret intelligence; this is what the Grand Duke does not know; and this is what he must know!”

“Well, sire, an intelligent, courageous courier. . .”

“I momentarily expect one.”

“And it is to be hoped he will be expeditious,” added the chief of police; “for, allow me to add, sire, that Siberia is a favourable land for rebellions.”

“Do you mean to say, General, that the exiles would make common cause with the rebels?” exclaimed the Czar, indignant at the insinuation.

“Excuse me, your majesty,” stammered the chief of police, for that was really the idea suggested to him by his uneasy and suspicious mind.

“I believe in their patriotism,” returned the Czar.

“There are other offenders besides political exiles in Siberia,” said the chief of police.

“The criminals? Oh, General, I give those up to you! They are the vilest, I grant, of the human race. They belong to no country. But the insurrection, or rather the rebellion, is not to oppose the emperor; it is raised against Russia, against the country which the exiles have not lost all hope of again seeing—and which they will see again. No, a Russian would never unite with a Tartar, to weaken, were it only for an hour, the Muscovite power!”

The Czar was right in trusting to the patriotism of those whom his policy kept, for a time, at a distance. Clemency, which was the foundation of his justice, when he could himself direct its effects, the modifications he had adopted with regard to applications for the formerly terrible ukases, warranted the belief that he was not mistaken. But even without this powerful element of success in regard to the Tartar rebellion, circumstances were not the less very serious; for it was to be feared that a large part of the Kirghiz population would join the rebels.

The Kirghiz are divided into three hordes, the greater, the lesser, and the middle, and number nearly four hundred thousand “tents,” or two million souls. Of the different tribes some are independent and others recognize either the sovereignty of Russia or that of the Khans of Khiva, Khokhand, and Bokhara, the most formidable chiefs of Turkestan. The middle horde, the richest, is also the largest, and its encampments occupy all the space between the rivers Sara Sou, Irtish, and the Upper Ishim, Lake Saisang and Lake Aksakal. The greater horde, occupying the countries situated to the east of the middle one, extends as far as the governments of Omsk and Tobolsk. Therefore, if the Kirghiz population should rise, it would be the

rebellion of Asiatic Russia, and the first thing would be the separation of Siberia, to the east of the Yenisei.

It is true that these Kirghiz, mere novices in the art of war, are rather nocturnal thieves and plunderers of caravans than regular soldiers. As M. Levchine says, “a firm front or a square of good infantry could repel ten times the number of Kirghiz; and a single cannon might destroy a frightful number.”

That may be; but to do this it is necessary for the square of good infantry to reach the rebellious country, and the cannon to leave the arsenals of the Russian provinces, perhaps two or three thousand versts distant. Now, except by the direct route from Ekaterenburg to Irkutsk, the often marshy steppes are not easily practicable, and some weeks must certainly pass before the Russian troops could be in a position to subdue the Tartar hordes.

Omsk is the centre of that military organization of Western Siberia which is intended to overawe the Kirghiz population. Here are the bounds, more than once infringed by the half-subdued nomads, and there was every reason to believe that Omsk was already in danger. The line of military stations, that is to say, those Cossack posts which are ranged in echelon from Omsk to Semipolatinsk, must have been broken in several places. Now, it was to be feared that the “Grand Sultans,” who govern the Kirghiz districts would either voluntarily accept, or involuntarily submit to, the dominion of Tartars, Mussulmen like themselves, and that to the hate caused by the slavery was not united the hate due to the antagonism of the Greek and Mussulman religions. For some time, indeed, the Tartars of Turkestan, and principally those from the khanats of Bokhara, Khiva, Khokhand, and Koondooz, endeavoured, by employing both force and persuasion, to subdue the Kirghiz hordes to the Muscovite dominion.

A few words only with respect to these Tartars.

The Tartars belong more especially to two distinct races, the Caucasian and Mongolian.

The Caucasian race, which, as Abel de Rémusat says, “is regarded in Europe as the type of beauty in our species, because all the nations in this part of the world have sprung from it,” unites under the same denomination the Turks and the natives of Persia.

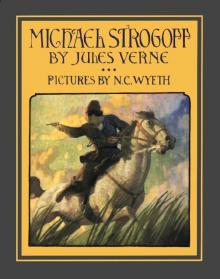

Michael Strogoff; Or the Courier of the Czar: A Literary Classic

Michael Strogoff; Or the Courier of the Czar: A Literary Classic Voyage au centre de la terre. English

Voyage au centre de la terre. English Journey Through the Impossible

Journey Through the Impossible The Castaways of the Flag

The Castaways of the Flag L'île mystérieuse. English

L'île mystérieuse. English Maître du monde. English

Maître du monde. English Around the World in Eighty Days

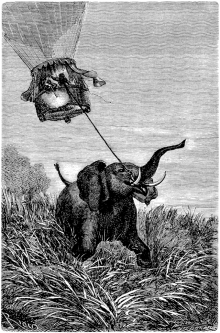

Around the World in Eighty Days A Voyage in a Balloon

A Voyage in a Balloon From the Earth to the Moon, Direct in Ninety-Seven Hours and Twenty Minutes: and a Trip Round It

From the Earth to the Moon, Direct in Ninety-Seven Hours and Twenty Minutes: and a Trip Round It Paris in the Twentieth Century

Paris in the Twentieth Century City in the Sahara - Barsac Mission 02

City in the Sahara - Barsac Mission 02 The English at the North Pole

The English at the North Pole The Field of Ice

The Field of Ice From the Earth to the Moon

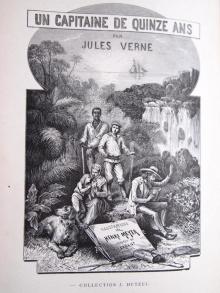

From the Earth to the Moon Un capitaine de quinze ans. English

Un capitaine de quinze ans. English The Mysterious Island

The Mysterious Island Les indes-noirs. English

Les indes-noirs. English Robur-le-conquerant. English

Robur-le-conquerant. English Propeller Island

Propeller Island Around the World in Eighty Days. Junior Deluxe Edition

Around the World in Eighty Days. Junior Deluxe Edition Les forceurs de blocus. English

Les forceurs de blocus. English In the Year 2889

In the Year 2889 Journey to the Centre of the Earth

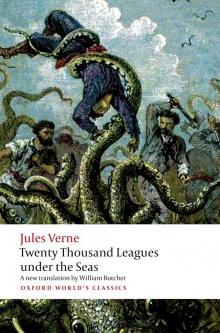

Journey to the Centre of the Earth Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea From the Earth to the Moon; and, Round the Moon

From the Earth to the Moon; and, Round the Moon Vingt mille lieues sous les mers. English

Vingt mille lieues sous les mers. English Cinq semaines en ballon. English

Cinq semaines en ballon. English Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas

Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas Face au drapeau. English

Face au drapeau. English Michael Strogoff; Or, The Courier of the Czar

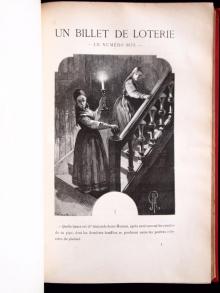

Michael Strogoff; Or, The Courier of the Czar Un billet de loterie. English

Un billet de loterie. English The Secret of the Island

The Secret of the Island Off on a Comet! a Journey through Planetary Space

Off on a Comet! a Journey through Planetary Space Into the Niger Bend: Barsac Mission, Part 1

Into the Niger Bend: Barsac Mission, Part 1 All Around the Moon

All Around the Moon A Journey to the Center of the Earth - Jules Verne: Annotated

A Journey to the Center of the Earth - Jules Verne: Annotated 20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 2

20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 2 Robur-le-Conquerant

Robur-le-Conquerant Les Index Noires

Les Index Noires Michael Strogoff; or the Courier of the Czar

Michael Strogoff; or the Courier of the Czar 20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 1

20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 1 Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Five Weeks In A Balloon

Five Weeks In A Balloon Journey to the Center of the Earth

Journey to the Center of the Earth 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday

Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday The Collected Works of Jules Verne: 36 Novels and Short Stories (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics)

The Collected Works of Jules Verne: 36 Novels and Short Stories (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics) The Survivors of the Chancellor

The Survivors of the Chancellor Their Island Home

Their Island Home Le Chateau des Carpathes

Le Chateau des Carpathes Les Cinq Cents Millions de la Begum

Les Cinq Cents Millions de la Begum The Floating Island

The Floating Island Cinq Semaines En Ballon

Cinq Semaines En Ballon Autour de la Lune

Autour de la Lune