- Home

- Jules Verne

Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday Page 20

Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday Read online

Page 20

‘I hope you will all be cautious and not be tempted into rashness by any desire to show off. If there is little fear of the ice breaking up, there is always a risk of your breaking an arm or a leg. So be careful. Do not go out of sight. If any of you get far away, remember that Gordon and I will wait for you here And when I give the signal, mind you all come back.’

And then the skaters went on the ice, and Briant was delighted to see how well they got along. The few falls that took place produced only shouts of laughter. The best performance was Jack’s. Forward and backward he flew, sometimes on one foot sometimes on two, sometimes upright, sometimes stooping, describing circles and curves with marvellous regularity; and great was Briant’s satisfaction to see his brother take part in his comrades’ games.

Probably Donagan felt annoyed at the applause with which Jack was greeted, as in spite of Briant’s warnings he drew farther and farther away from the rest, and made signs for Cross to follow him.

‘There’s a lot of wild duck over there,’ he said, ‘in the east; do you see them?’

‘Yes.’

‘You have got your gun! I have mine! Come on!’

‘But Briant says no.’

‘Never mind what Briant says. Come on, and be as quick as you can.’

And in a minute or two Donagan and Cross were half a mile away in pursuit of the flock of ducks that were flying across the lake. ‘Where are they off to?’ asked Briant ‘They have seen some birds over there,’ answered Gordon, ‘and the instinct of the sportsman—’

‘Or rather the instinct of disobedience,’ interrupted Briant. ‘It is Donagan again—’

‘Do you think anything will happen to them?’

‘Who can tell?’ said Briant ‘It is always dangerous to get away from the rest like that. Look how far they have gone already!’

And in their rapid rush Donagan and Cross were now merely two points on the horizon of the lake.

Even if they had time to return, for the day would last a few hours longer, it was unwise to go away so far. At this time of the year a sudden change of weather was always to be feared. A shift in the wind might at any moment mean a gale or a fog. And about two o’clock Briant saw with dismay that the horizon had disappeared in a thick bank of mist. Cross and Donagan had not reappeared, and the mist, growing thicker each moment, came up over the ice and hid the western shore.

‘That is what I feared,’ said Briant ‘And now how will they know their way back?’

‘Blow the horn! Give them a blast on the horn.’ said Gordon.

Three times the horn sounded, and the brazen note rang out over the ice. Perhaps it would be replied to by a report from the guns—the only means Donagan and Cross had of making their position known.

Briant and Gordon listened. No report reached their ears.

The fog had now increased, and was within a quarter of a mile of where they stood. The lake would soon be entirely hidden by it.

Briant called to those within sight, and a few minutes afterwards they were all safe on the bank.

‘What is to be done?’ asked Gordon.

‘Try all we can to find Cross and Donagan before they are lost in the fog. Let one of us be off in the direction they have gone and try to signal them back with the horn.’

‘I’ll go,’ said Baxter.

‘And so will we,’ said two or three others.

‘No! I will go! ‘said Briant.

‘Let me go, said Jack. ‘I can soon get up to Donagan on my skates.’

‘That will do,’ said Briant ‘Be off, Jack, and listen for the report of the guns. Take the horn, and that will tell them where you are.’

A moment afterwards Jack was invisible in the fog, which had become denser than ever. Briant Gordon, and the others listened attentively to the notes of the horn, which soon died away in the distance.

Half an hour elapsed. There was no news of the absent neither of Donagan and Cross, unable to find their bearings on the lake, nor of Jack who had gone to help them.

What would become of all of them if night fell before they returned.

‘If we had firearms,’ said Service, ‘we might—‘

‘Firearms!’ exclaimed Briant ‘there are some at French Den! Let us fetch them! Don’t lose a moment!’

It was the best thing to do, for above all things it was important to let Jack and Donagan and Cross know the way back.

In about half an hour Briant and the others were at the cave. There was no thought now of economizing powder. Wilcox and Baxter loaded two muskets and fired them towards the east. There was no reply, nor the sound of gun or horn.

It was now half-past three o’clock. The fog grew thicker as the sun sank behind Auckland Hill. The surface of the lake was invisible.

‘Fire a cannon,’ said Briant.

One of the little pieces from the schooner that pointed through the embrasure by the door of the hall was dragged out on to the terrace and pointed towards the north-east. It was loaded with a signal cartridge, and Baxter was about to fire it when Moko suggested that a wad of grass stuffed in above the cartridge would make the report louder. The gun was fired, and in such a calm atmosphere the report could have been heard several miles away. But there was no reply.

For an hour the cannon was fired every ten minutes. That Donagan, Cross, and Jack could misunderstand the meaning of this firing was impossible. The discharges could be heard over the whole surface of the lake, for in fog sound travels farther than in fine weather, and the denser the fog the better it travels.

At length, a little before five o’clock, two or three distant reports of a gun were heard in the north-east.

‘There they are!’ said Service.

And immediately Baxter fired in reply.

A few minutes afterwards two forms were seen through the mist that still lay thick on the lake, and Donagan and Cross came into view.

Jack was not with them.

Briant’s anxiety may be guessed. His brother had not been able to find the two runaways, who had heard nothing of the horn. Cross and Donagan had, in fact been coming back from the centre of the lake when Jack started eastwards, and without the firing from French Den they would have been unable to find their way.

Briant, thinking only of his brother thus lost in the fog, said not a word of reproach to Donagan, whose disobedience had caused such serious risk. If Jack had to pass the night on the lake in a temperature of thirteen below freezing, how could he survive?

‘I ought to have gone in his place,’ said Briant, when Gordon and Baxter in vain tried to give him a little hope.

A few more cannon-shots were fired. Evidently if Jack were near French Den he would have heard them, and replied with a blast on his horn. But not a sound came in answer. And night was closing in and darkness would soon settle down on the island.

One good thing happened. The fog showed a tendency to disappear. The breeze rising as the sun set, began to blow the mist back, and now the only difficulty in getting back to French Den lay in the darkness of the night.

There was now only one thing to do, —to light a large fire on the bank as a signal; and Wilcox, Baxter, and Service had begun to heap up the dry wood on the terrace when Gordon stopped them.

‘Wait!’ he said.

With the glass at his eyes, he was looking attentively towards the north-east.

‘I think I see something,’ he said, ‘something that moves.’

Briant had seized the glass and was looking through it.

‘Heaven be praised,’ he said, ‘it is Jack! I see him!’

And they all shouted their loudest as if they could make themselves heard at what must have been at least a mile away.

But the distance was lessening visibly. Jack with the skates on his feet came gliding on with the speed of an arrow towards French Den. In a few minutes he would be home.

‘I do not think he is alone!’ said Baxter, with a gesture of surprise.

The boys looked, and two other moving things

could be seen behind Jack a few hundred yards away from him.

‘What is that?’ asked Gordon.

‘Men?’ asked Baxter.

‘No! Beasts!’ said Wilcox.

‘Wild beasts probably,’ said Donagan.

He was not mistaken, and without a moment’s hesitation he rushed on to the lake towards Jack. In a minute he had reached the boy, and fired at the two pursuers, who turned tail and fled.

They were two bears, quite an unexpected addition to the Charmanian fauna! if they had been prowling about the island all this time how was it no trace of them had been seen? Could it be that they only inhabited the island in the winter, and that they had drifted to it on the floating ice? Did not that seem to show that a continent was not far from Charman Island? Here was food for reflection.

But Jack was saved, and his brother clasped him in his arms, and great was the general rejoicing at his return. He had blown his horn again and again without attracting the attention of his comrades, who like him were unable to fix their position in the fog until the cannon-shots were heard.

‘That must be the cannon at French Den,’ said he, when he heard the sound.

He was then several miles away on the north-east side of the lake, and at once he set off full speed towards the point from which the report proceeded. Suddenly as the fog began to clear he saw the two bears rushing in pursuit of him. He did not however, lose his presence of mind, and his progress was swift enough to keep the animals at a distance; but if he had fallen he would have been lost.

While he and his brother were going back to the cave he took him aside, and said in a low voice, —

‘Thank you much for giving me a chance.’

Briant clasped his hand and said nothing.

As Donagan was entering the door, Briant said to him, —

‘I told you not to go far away, and you see how your disobedience might have caused a great disaster. But although you are much to blame, Donagan, I cannot do less than thank you for having gone to Jack’s help.’

‘I only did my duty,’ said Donagan coldly.

And he passed on without noticing the hand his comrade held out to him.

CHAPTER V—THE SEPARATION.

Six weeks after these events, about five o’clock in the evening, four of the young colonists came to a halt at the southern extremity of Family Lake.

It was the 10th of October. The influence of the warm season was making itself felt. Beneath the trees, clothed in their fresh verdure, the ground had resumed the garb of spring. A pleasant breeze rippled the surface of the water, now lighted by the last rays of the sun which lingered on the vast plain of South Moors. A narrow beach of sand formed the border of the moor. Flocks of birds with much noise flew overhead on their way to rest for the night in the shadow of the woods or the crevices of the cliff. A few groups of evergreen trees, pines, green oaks, and a few acres of firs alone broke the monotonous barrenness of this part of Charman Island.

A fire was burning at the foot of a pine-tree, and its fragrant smoke was drifting over the marsh. A couple of ducks were cooking over the fire. Supper over, the four boys had nothing to do but to wrap themselves up in their rugs, and, while one watched, three of them could sleep.

They were Donagan, Cross, Webb, and Wilcox. And the circumstances under which they had separated from their companions were these.

During the later months of the second winter, the relations between Donagan and Briant had become more strained than ever. It will not have been forgotten with what envy Donagan had seen the election of his rival.

More jealous and irritable than ever, it was with the greatest difficulty he submitted to the orders of the new chief of Charman Island. That he did not resist openly was because the majority would not support him; but on many occasions he had showed such ill-will that Briant had found it his duty to remonstrate with him. Since the skating party, when his disobedience had been so flagrant, his insubordination had gone on increasing, and the time had come when Briant would be obliged to punish him.

Gordon was very uneasy at this state of things, and had made Briant promise that he would restrain himself. But the latter felt that his patience was at an end, and that for the common interest in the preservation of order an example had become necessary. In vain Gordon had tried to bring back Donagan to a sense of his position. If he had had any influence over him in the past, he now found it had entirely disappeared. Donagan would not forgive him for having so often sided with his rival, and his efforts at reconciliation being in vain, he saw with regret the complications that were coming.

From this state of things it resulted that the harmony so indispensable to the peace of French Den was destroyed. A certain restraint was obvious which made the life in common very uncomfortable. Except at mealtimes Donagan and his three partisans lived apart. When bad weather kept them indoors they would gather together in a corner of the hall, and there hold whispered conversations.

‘Most certainly,’ said Briant to Gordon one day, ‘those three are plotting something.’

‘Not against you, Briant,’ said Gordon. ‘Donagan dare not try to take your place. We are all on your side, and he knows it.’

‘Perhaps they are thinking of separating from us?’

‘That is more likely, and I do not see that we have the right to prevent them.’

‘But to go and set up—’

‘They may not be going to do so.’

‘But they are! I saw Wilcox making a copy of Baudoin’s map, and—’

‘Did Wilcox do that?’

‘Yes; and really I think it would be better for me to put an end to all this by resigning in your favour, or perhaps in Donagan’s. That would cut short all this rivalry.’

‘No, Briant,’ said Gordon decidedly, ‘you would fail in your duty towards those who have elected you.’

Amid these discussions the winter came to an end. With the first days of October the cold definitely disappeared, and the surface of the lake and river became free from ice. And on the evening of the 9th of the month Donagan announced the resolve of himself and Webb, Cross, and Wilcox to leave French Den.

‘You wish to abandon us?’ said Gordon.

‘To abandon you? No, Gordon!’ said Donagan. Only Cross, Wilcox, Webb, and I have agreed to move to another part of the island.’

‘And for what reason?’ asked Baxter.

‘Simply because we want to live as we please, and I tell you frankly because it does not suit us to take orders from Briant.’

‘What have you to complain of about me?’ said Briant.

‘Nothing—except your being at our head,’ said Donagan. ‘We had a Yankee as chief of the colony—now it is a French fellow who is in command! Next time I suppose we shall have a nigger fellow, Moko for instance—‘

‘Do you mean that?’ asked Gordon.

‘I do,’ said Donagan, ‘and neither I nor my friends care to serve under any but one of our own race.’

‘Very well,’ said Briant, ‘Wilcox, Webb, Cross, and you, Donagan, are quite at liberty to go, and take away your share of the things.’

‘We never supposed otherwise, Briant; and to-morrow we will clear out of French Den.’

‘And may you never have cause to repent of your determination,’ said Gordon, who saw that insistance would be in vain.

Donagan’s plan was as follows. When Briant had told the story of his expedition across the lake he had stated that the little colony could take up their quarters on the eastern side of the island under very favourable conditions. Among the rocks on the shore were many caves, the river yielded fresh water in abundance. The forest extended to the beach, there was game furred and feathered in abundance, and life would be as easy there as at French Den, and much easier than at Schooner Bay. Besides, the distance between French Den and the coast was only a dozen miles, of which six were across the lake and six down the East River, so that in case of necessity communication was not difficult.

But it was not by w

ater that Donagan proposed to reach Deception Bay. His plan was to coast along Family Lake to its southern point, and then follow the bank to East River, exploring a country up to then unknown. This was a longish journey—fifteen or sixteen miles—but he and his friends would treat the trip as a sporting expedition and get some shooting as they went Donagan had thus no need of the yawl, and contented himself with the Halkett boat which would suffice for the passage of East River and any other streams he might meet with.

As this expedition was merely preliminary, and had for its object the exploration of Deception Bay, with a view of selecting a permanent dwelling, Donagan took no more baggage with him than he could help. Two guns, four revolvers, two axes, sufficient ammunition, a few fishing lines, some travelling-rugs, one of the pocket compasses, the indiarubber boat and a few preserves, formed the outfit.

The expedition was expected to last about a week, and when they had selected their future home, Donagan and his friends would return to French Den and take away on the chariot their share of the articles saved from the wreck of the schooner. If Gordon or any of the rest came to visit them, they would be glad to see them, but to continue to live at French Den under the present state of things, they had no intention of doing, and nothing could shake their determination to set up a little colony of their own.

At sunrise the four separatists took leave of their comrades, who were very sorry to see them go, and, maybe, Donagan and his friends were not unmoved.

They were taken across Zealand River in the yawl by Moko, and then leisurely walked off along the shore of Family Lake by the edge of the wide-stretching South Moors.

A few birds were killed as they went along by the side of the marsh, but Donagan, knowing he must be careful of his ammunition, contented himself with only shooting enough for the day’s rations. That day the boys accomplished between five and six miles, and about five o’clock in the evening, arriving at the end of the lake, they camped for the night.

The night was cold, but the fire kept them comfortable, and all four were awake at the dawn. The southern extremity of Family Lake was an acute angle formed by two high banks, the right one of which ran due north. On the east the country was still marshy, but the ground was a few feet above the level of the lake, so that it was not flooded. Here and there a few knolls dotted with under-sized trees broke the monotony of the green expanse. As the country consisted chiefly of sandhills Donagan gave it the name of Dune Lands; and not wishing to plunge too far into the unknown, he decided to keep to the lake shore, and leave further exploration for a future time.

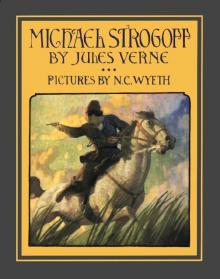

Michael Strogoff; Or the Courier of the Czar: A Literary Classic

Michael Strogoff; Or the Courier of the Czar: A Literary Classic Voyage au centre de la terre. English

Voyage au centre de la terre. English Journey Through the Impossible

Journey Through the Impossible The Castaways of the Flag

The Castaways of the Flag L'île mystérieuse. English

L'île mystérieuse. English Maître du monde. English

Maître du monde. English Around the World in Eighty Days

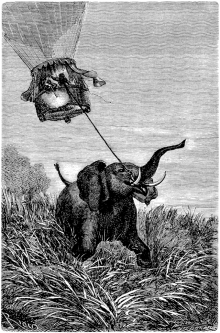

Around the World in Eighty Days A Voyage in a Balloon

A Voyage in a Balloon From the Earth to the Moon, Direct in Ninety-Seven Hours and Twenty Minutes: and a Trip Round It

From the Earth to the Moon, Direct in Ninety-Seven Hours and Twenty Minutes: and a Trip Round It Paris in the Twentieth Century

Paris in the Twentieth Century City in the Sahara - Barsac Mission 02

City in the Sahara - Barsac Mission 02 The English at the North Pole

The English at the North Pole The Field of Ice

The Field of Ice From the Earth to the Moon

From the Earth to the Moon Un capitaine de quinze ans. English

Un capitaine de quinze ans. English The Mysterious Island

The Mysterious Island Les indes-noirs. English

Les indes-noirs. English Robur-le-conquerant. English

Robur-le-conquerant. English Propeller Island

Propeller Island Around the World in Eighty Days. Junior Deluxe Edition

Around the World in Eighty Days. Junior Deluxe Edition Les forceurs de blocus. English

Les forceurs de blocus. English In the Year 2889

In the Year 2889 Journey to the Centre of the Earth

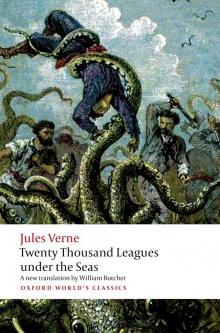

Journey to the Centre of the Earth Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea From the Earth to the Moon; and, Round the Moon

From the Earth to the Moon; and, Round the Moon Vingt mille lieues sous les mers. English

Vingt mille lieues sous les mers. English Cinq semaines en ballon. English

Cinq semaines en ballon. English Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas

Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas Face au drapeau. English

Face au drapeau. English Michael Strogoff; Or, The Courier of the Czar

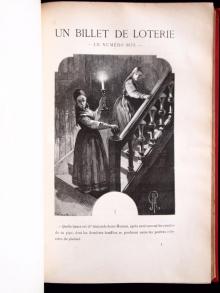

Michael Strogoff; Or, The Courier of the Czar Un billet de loterie. English

Un billet de loterie. English The Secret of the Island

The Secret of the Island Off on a Comet! a Journey through Planetary Space

Off on a Comet! a Journey through Planetary Space Into the Niger Bend: Barsac Mission, Part 1

Into the Niger Bend: Barsac Mission, Part 1 All Around the Moon

All Around the Moon A Journey to the Center of the Earth - Jules Verne: Annotated

A Journey to the Center of the Earth - Jules Verne: Annotated 20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 2

20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 2 Robur-le-Conquerant

Robur-le-Conquerant Les Index Noires

Les Index Noires Michael Strogoff; or the Courier of the Czar

Michael Strogoff; or the Courier of the Czar 20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 1

20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 1 Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Five Weeks In A Balloon

Five Weeks In A Balloon Journey to the Center of the Earth

Journey to the Center of the Earth 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday

Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday The Collected Works of Jules Verne: 36 Novels and Short Stories (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics)

The Collected Works of Jules Verne: 36 Novels and Short Stories (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics) The Survivors of the Chancellor

The Survivors of the Chancellor Their Island Home

Their Island Home Le Chateau des Carpathes

Le Chateau des Carpathes Les Cinq Cents Millions de la Begum

Les Cinq Cents Millions de la Begum The Floating Island

The Floating Island Cinq Semaines En Ballon

Cinq Semaines En Ballon Autour de la Lune

Autour de la Lune