- Home

- Jules Verne

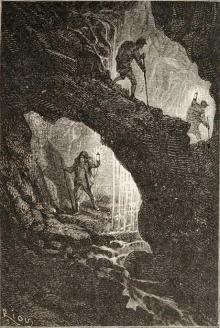

Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Page 27

Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Read online

Page 27

Chesneaux, Jean. Jules Verne, un regard sur le monde: Nouvelles lectures politiques. Paris: Bayard, 2001.

Compere, Daniel. Un voyage imaginaire de Jules Verne : Voyage au centre de la terre. Paris: Lettres Modernes, 1977.

Fabre, Michel. Le problème et l’epreuve: Formation et modernité chez Jules Verne. Paris: Harmattan, 2004.

Raymond, Francois, ed. La science en question. Paris: Minard, 1992. Serres, Michel. Jouvences sur Jules Verne. Paris: Minuit, 1974.

_ Jules Verne, la science et l’homme contemporain. Paris: Pommier, 2003.

Vierne, Simone. Jules Verne. Paris: Balland, 1986.

a Famous school in Hamburg.

b Literally, “League of Virtue”; a civic association in early-nineteenth-century Germany.

c Town and province in modern Estonia.

d Nineteenth-century bookbinders.

e Snorri Sturluson (1179-1241) was an Icelandic poet, historian, and leader; his work Heimskringla is a collection of sagas.

f The runic alphabet was used by Germanic peoples in Britain, northern Europe, and Iceland from approximately the third century to the sixteenth century.

g Galileo discovered the rings of Saturn with a primitive telescope in 1610 but misinterpreted the unclear images he perceived as being those of a triple planet system.

h District of Hamburg.

i The two principal rivers flowing through Hamburg.

j First day of the month in the Roman calendar.

k Device that stores static electricity.

l Perhaps a reference to the German geographer August Heinrich Petermann (1822-1878), a specialist on Africa and the Arctic.

m Name given to narrow gulfs in the Scandinavian countries (author’s note).

n Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Fourier (1768-1830), French mathematician who became famous through his work The Analytical Theory of Heat ( 1822).

o Siméon-Denis Poisson (1781-1840), French mathematician who wrote extensively on the application of mathematics to such areas of physics as electricity and mechanics. Lidenbrock is referring to his Mathematical Theory of Heat (1835).

p Lübeck is a city in northern Germany; Helgoland is a German island and vacation resort in the North Sea.

q Kiel is a port city in northern Germany. The Belts are two straits in Denmark that connect the Baltic Sea with the large strait called the Kattegat. Holstein is the region between the Eider and Elbe Rivers, now the southern part of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein.

r Approximately 2 francs and 75 centimes (author’s note).

s Bertel Thorvaldsen, Danish neoclassical sculptor (c.1770-1844).

t English name for the Danish city of Helsingør, the site of Castle Kronberg, the original setting of Shakespeare’s tragedy Hamlet.

u Castle Kronberg and the city of Helsingør lie across a sound from Helsingborg. Both these Swedish cities are at the entrance to the Kattegat, a strait between Sweden and Denmark that forms part of the connection between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea.

v The Skagerrak is an arm of the North Sea that lies between Denmark and Norway; Cape Lindesnes is located at the southernmost tip of Norway.

w Mykines is actually the island farthest to the west.

x The geographical reference point is unclear.

y Yet in the process of deciphering Saknussemm’s manuscript, Axel had in fact identified what he thought were French and Hebrew elements.

z The Index Prohibitorius, which specified books forbidden by the Roman Catholic Church.

aa La Recherche was sent out in 1835 by Admiral Duperré to learn the fate of the lost expedition of Mr. de Blosseville and the Lilloise, which was never heard of again (author’s note). See also endnote 6.

ab Just over 100 statute miles.

ac 16 francs 98 centimes (author’s note).

ad A Ruhmkorff device consists of a Bunsen battery operated by means of potassium dichromate, which does not smell; an induction coil puts the electricity generated by the battery in contact with a lantern of a particular design; in this lantern there is a spiral glass tube that contains a vacuum with only a residue of carbon dioxide or nitrogen. When the device is operative, this gas becomes luminous, producing a steady whitish light. The battery and coil are placed into a leather bag that the traveler carries on a shoulder strap. The lantern, carried outside, supplies quite sufficient light even in deep darkness; it allows one to venture into the midst of the most inflammable gases without fear of explosions, and it is not extinguished even in the deepest waters. Mr. Ruhmkorff is a scholar and skilled physicist; his great discovery is the induction coil, which allows one to generate high-tension electricity. In 1864, he won the five-year prize of 50,000 francs reserved by the French government for the most ingenious application of electricity (author’s note).

ae Danish mathematician (1788-1876) who traveled to Iceland between 1831 and 1843 to carry out a large-scale topographical survey and design maps on a grant from the Copenhagen Literature Society.

af And wherever fortune opens up a path, we will follow (Latin; from Virgil’s Aeneid 11.128).

ag Icelandic farmer’s house (author’s note).

ah Eight leagues (author’s note).

ai A gigantic statue of the sun god Helios, built between 294 and 282 B.C. in the ancient Greek city of Rhodes.

aj The rivers Alfta and Hitard in Iceland.

ak In Hamburg currency, about 90 francs (author’s note).

al In chapter VI, Professor Lidenbrock had indicated 1219 as the last eruption date (see p. 31; in fact, it was about A.D. 200.).

am Rocks containing silicates of magnesium, iron, and calcium.

an God of the underworld in Greek mythology.

ao The descent to Hell is easy (Latin; from Virgil’s Aeneid 6.126); the literal meaning of the phrase—“the descent to Avernus is easy”—refers to Lake Avernus, near what is now Naples, Italy; the lake was once believed to be an entrance to the underworld.

ap So called because the soils of this period are wide-spread in England, in the regions once inhabited by the celtic tribe of the Silurians (author’s note). The Silurian period occurred 438 to 410 million years ago.

aq That is, who take a long detour to reach a place nearby.

ar Fucus is a type of brown algae; lycopods are club mosses, spore-bearing evergreen plants with leaves that resemble needles.

as That is, soils of the Devonian period (410-360 million years ago).

at Primitive fishes that have thick, bony scales with a shiny surface.

au 360-286 million years ago.

av Sigillaria is a tree-size lycopod that is found as a fossil in ancient coal formations, where the asterophyllite, a fossil plant, also occurs.

aw Spa is a famous site of therapeutic hot springs in Belgium. Töplitz is the German name for Teplice, a town in what is today the north of the Czech Republic; it was a famous spa in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

ax Bach is the German word for creek.

ay John Cleves Symmes (1780-1829), a former American army officer and an ardent advocate of a theory that the Earth is hollow and has entrances thousands of miles wide at the poles.

az Goddess of the underworld in Roman mythology.

ba Verne is confused. German explorer Alexander von Humboldt visited the Cuevas del Guácharo in Venezuela in 1799 and wrote about them in 1816. Von Humboldt never visited Guácharo Cave in Colombia.

bb Jean-Baptiste-François Bulliard (1752-1793), French botanist who researched and published extensively on plants and fungi.

bc Calcium phosphate (author’s note).

bd The mastodon and the deinotherium were elephant-like species of fossil mammals; the megatherium was a type of ground-dwelling sloth that is now extinct.

be Literally, this term means “in the middle of the Earth.”

bf Scottish explorer (1800-1862) who investigated magnetic phenomena in the Arctic and Antarctic and discovered the magnetic north pole in 1831.

bg Genus of fish with two fi

ns.

bh Georges Cuvier (1769-1832), French statesman and zoologist who did ground-breaking work on comparative anatomy and paleontology and extensively studied fossil animals.

bi Oceans of the Secondary period that generated the soil which the Jura Mountains consist of (author’s note). Jurassic period: 208-144 million years ago.

bj Blue argillaceous limestone that occurs in southwestern England; it also forms part of Jurassic layers that typically contain many fossils.

bk Extinct marine animal with the body of a fish, a head like a dolphin’s, and flippers.

bl Extinct marine reptile with a long neck, typically found in fossils from about 200 million years ago.

bm Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1752-1840), German physiologist and founder of physical anthropology, proposed one of the first classifications of humans into different races.

bn Very famous spring at the foot of Mount Hekla (author’s note). Mount Hekla is in southern Iceland.

bo Clouds in round shapes (author’s note).

bp One of the protagonists of the Trojan War; as described in Homer’s Iliad. Ajax was second only to Achilles himself. But when a prize for courage, Achilles’ armor, was given to Odysseus rather than to him, his pride led him to treachery and suicide.

bq Extinct animal that resembled an armadillo but was the size of a cow. The Pliocene epoch (5-1.8 million years ago) is the most recent part of the Tertiary period (65 to 1.8 million years ago).

br Beginning of the text Verne added in the edition of 1867 to reflect discoveries about Stone Age humans that the French archaeologist Jacques Boucher de Perthes made; see the introduction, p. xxi.

bs Jean-Louis-Armand de Quatrefages de Bréau (1810-1892), a friend of Milne-Edwards (see endnote 1) and also a noted zoologist and anthropologist.

bt The shortest and most recent geological period, which followed the Tertiary and began 1.8 million years ago.

bu Prominent French geologist (1798-1874), one of the principal proponents of catastrophism—the theory that the Earth was shaped not by continuous development but by cataclysmic upheavals—and maker of a geological map of France. ‡Geological deposits formed by sudden floods of water, in contrast with alluvial deposits, which are built up through slower, more continuous water flows.

bv Mammoth that lived in Western Europe at the end of the Pliocene epoch, some 5 million years ago.

bw American showman Phineas Taylor Barnum (1810-1891) founded a museum famous for its freakish and abnormal specimens; he participated in the 1869 hoax surrounding “Cardiff Man,” an alleged fossil man of gigantic height. Barnum created a fake reproduction of the already fake original fossil to exhibit in his museum.

bx The facial angle is shaped by two planes, one more or less vertical that touches the brow and the front teeth, the other one horizontal, going through the opening of the ear canal to the lower nasal cavity. In anthropological language, prognathism is defined as the projection of the jaw-bone that modifies the facial angle (author’s note).

by In Greek mythology the god Proteus could change his shape at will. Neptune was the god of the oceans in Roman mythology.

bz The shepherd of huge herds, and huger still himself (Latin). The language plays on a passage in Virgil’s Bucolica: “a shepherd of fine herds, and finer still himself.” Victor Hugo adapted the form that Verne quotes here for his novel Notre-Dame de Paris (The Hunchback of Notre Dame).

ca Edouard Lartet (1801-1871), French paleontologist who discovered a fossil anthropoid at Sansan in 1834 that he named pliopithecus.

cb End of the text that Verne added in the 1867 edition.

cc Verne mixes up the geographical information here. Jan Mayen Island, which belongs to Norway administratively, lies in the Arctic Ocean between Greenland and Norway, several hundred miles southeast of Spitzbergen, a group of islands on the Arctic Circle; its volcano is called Beerenberg, not Esk.

cd Where are we? (Italian). The question below translates as “What is this island called?”

ce Stromboli (Strongyle in Latin) is a volcanically active island off the northeastern coast of Sicily. ‡God of the winds in Greek mythology.

cf City in northeastern Sicily.

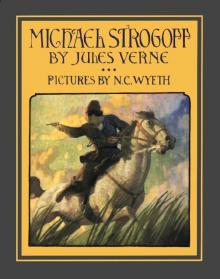

Michael Strogoff; Or the Courier of the Czar: A Literary Classic

Michael Strogoff; Or the Courier of the Czar: A Literary Classic Voyage au centre de la terre. English

Voyage au centre de la terre. English Journey Through the Impossible

Journey Through the Impossible The Castaways of the Flag

The Castaways of the Flag L'île mystérieuse. English

L'île mystérieuse. English Maître du monde. English

Maître du monde. English Around the World in Eighty Days

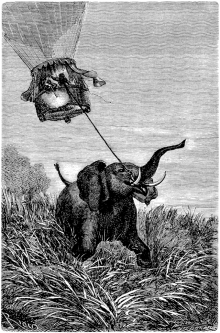

Around the World in Eighty Days A Voyage in a Balloon

A Voyage in a Balloon From the Earth to the Moon, Direct in Ninety-Seven Hours and Twenty Minutes: and a Trip Round It

From the Earth to the Moon, Direct in Ninety-Seven Hours and Twenty Minutes: and a Trip Round It Paris in the Twentieth Century

Paris in the Twentieth Century City in the Sahara - Barsac Mission 02

City in the Sahara - Barsac Mission 02 The English at the North Pole

The English at the North Pole The Field of Ice

The Field of Ice From the Earth to the Moon

From the Earth to the Moon Un capitaine de quinze ans. English

Un capitaine de quinze ans. English The Mysterious Island

The Mysterious Island Les indes-noirs. English

Les indes-noirs. English Robur-le-conquerant. English

Robur-le-conquerant. English Propeller Island

Propeller Island Around the World in Eighty Days. Junior Deluxe Edition

Around the World in Eighty Days. Junior Deluxe Edition Les forceurs de blocus. English

Les forceurs de blocus. English In the Year 2889

In the Year 2889 Journey to the Centre of the Earth

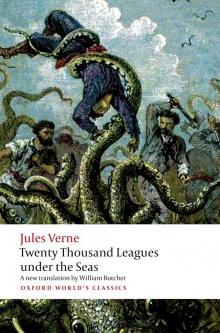

Journey to the Centre of the Earth Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea From the Earth to the Moon; and, Round the Moon

From the Earth to the Moon; and, Round the Moon Vingt mille lieues sous les mers. English

Vingt mille lieues sous les mers. English Cinq semaines en ballon. English

Cinq semaines en ballon. English Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas

Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas Face au drapeau. English

Face au drapeau. English Michael Strogoff; Or, The Courier of the Czar

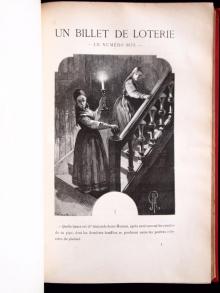

Michael Strogoff; Or, The Courier of the Czar Un billet de loterie. English

Un billet de loterie. English The Secret of the Island

The Secret of the Island Off on a Comet! a Journey through Planetary Space

Off on a Comet! a Journey through Planetary Space Into the Niger Bend: Barsac Mission, Part 1

Into the Niger Bend: Barsac Mission, Part 1 All Around the Moon

All Around the Moon A Journey to the Center of the Earth - Jules Verne: Annotated

A Journey to the Center of the Earth - Jules Verne: Annotated 20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 2

20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 2 Robur-le-Conquerant

Robur-le-Conquerant Les Index Noires

Les Index Noires Michael Strogoff; or the Courier of the Czar

Michael Strogoff; or the Courier of the Czar 20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 1

20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 1 Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Five Weeks In A Balloon

Five Weeks In A Balloon Journey to the Center of the Earth

Journey to the Center of the Earth 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday

Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday The Collected Works of Jules Verne: 36 Novels and Short Stories (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics)

The Collected Works of Jules Verne: 36 Novels and Short Stories (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics) The Survivors of the Chancellor

The Survivors of the Chancellor Their Island Home

Their Island Home Le Chateau des Carpathes

Le Chateau des Carpathes Les Cinq Cents Millions de la Begum

Les Cinq Cents Millions de la Begum The Floating Island

The Floating Island Cinq Semaines En Ballon

Cinq Semaines En Ballon Autour de la Lune

Autour de la Lune