- Home

- Jules Verne

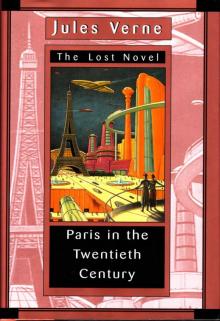

Paris in the Twentieth Century Page 7

Paris in the Twentieth Century Read online

Page 7

"Is Monsieur Jacques, " inquired Michel, "similarly obliged to ply some rebarbative trade?"

"Jacques is a shipping clerk in an industrial company, " Quinsonnas explained, "which does not mean, to his great regret, that he has ever seen the inside of a ship. "

"What does it mean?" asked Michel.

"It means, " Jacques replied, "that I'd have liked to be a soldier. "

"A soldier!" Michel betrayed his astonishment.

"Yes, a soldier. A noble profession in which, barely fifty years ago, you could earn an honest living!"

"Unless you lost it even more honestly, " Quinsonnas added. "Well, it's over and done with as a career, since there's no more army—unless you become a policeman. In other times, Jacques would have entered some military academy, or joined up, and there, after a life of battle, he would have become a general like a Turenne, or an emperor like a Bonaparte! But nowadays, my handsome officer, you'll have to give that all up. "

"Oh, you never know!" said Jacques. "It's true that France, England, Russia, and Italy have dismissed their soldiers; during the last century the engines of warfare were perfected to such a degree that the whole thing had become ridiculous—France couldn't help laughing—"

"And having laughed, " Quinsonnas put in, "she disarmed. "

"Yes, you joker! I grant you that with the exception of old Austria, the European peoples have done away with the military state. But for all that, have they done away with the spirit of battle natural to human beings, and the spirit of conquest natural to governments?"

"Probably, " remarked the musician.

"And why?"

"Because the best reason those instincts had for existing was the possibility of satisfying them! Because nothing suggests battle so much as an armed peace, according to the old expression! Because if you do away with painters there's no more painting, sculptors, no more sculpture, musicians, no more music, and if you do away with warriors—no more wars! Soldiers are artists. "

"Yes, of course!" Michel exclaimed, "and rather than do the awful work I do, I ought to join up. "

"Ah, you fell for it, baby!" Quinsonnas crowed. "Is there any possibility that you'd like to fight?"

"Fighting ennobles the soul, " Michel replied, "at least according to Stendhal, one of the great thinkers of the last century."

"Yes, it does, " the pianist agreed, but added, "How much brains does it take to give a good thrust with a saber?"

"A lot, if you're going to do it right, " Jacques answered.

"And even more, if you're going to receive the thrust, " Quinsonnas retorted. "My word, my friends, it's likely you're right, from a certain point of view. Perhaps I'd be inclined to make you a soldier, if there was still an army; with a little philosophy, it's a fine career. But nowadays, since the Champs-de-Mars has been turned into a school, we must give up fighting. "

"We'll go back to it, " said Jacques; "one fine day, some unexpected complication will arise..."

"I don't think so, my brave friend, for our bellicose notions are fading away, and with them our honorable ideas.... In France in the old days, men were afraid of ridicule, but do you think such a thing as a point of honor still exists? There are no duels fought nowadays; the fashion is past; we either compromise or we sue; now, if we no longer fight for honor's sake, why should we do it for politics? If individuals no longer take sword in hand, why should governments pull them from the scabbards? Battles were never more numerous than in the days of duels, and if there are no more duelists, then there are no more soldiers. "

"Oh, new ones will be born, " Jacques declared.

"I doubt it, since the links of commerce are drawing nations ever closer together! The British, the Russians, the Americans all have their banknotes, their rubles, their dollars invested in our commercial enterprises. Isn't money the enemy of the bullet? Hasn't the cotton bale replaced the cannonball? Just think, Jacques! Aren't the British enjoying a privilege they deny us, and gradually becoming the great landowners of France? They possess enormous territories, almost départements now, not conquered but bought, which is a lot more permanent! No one realized what was happening, we just let it happen, and soon these foreigners will own our entire country, and that's when they'll take their revenge on William the Conqueror!"

"My dear fellow, " Jacques replied, "remember this, and you too, young man, listen to what I say, for it's the century's profession of faith: With Montaigne and maybe Rabelais it was What Do I Know? In the nineteenth century it was What Does It Matter to Me? And nowadays we say: How Much Does It Earn? Well, the day a war earns as much as an industrial investment, then there'll be wars. "

"Good! War has never earned anything, especially for France. "

"Because we fought for honor and not for money, " Jacques replied.

"So you believe in an army of intrepid businessmen?"

"Of course. Look at the Americans in their dreadful War of Secession. "

"Well, my friend, an army that fights for a financial motive will no longer be composed of soldiers, but of looters and thieves!"

"All the same, such an army will accomplish wonders. "

"Thieving wonders, " Quinsonnas put in. And the three young men burst out laughing. "To conclude, " resumed the pianist, "here we have Michel, a poet, and Jacques, a soldier, and Quinsonnas, a musician, and this at a moment when our country no longer has music, or poetry, or an army! We are, quite obviously, stupid, all three of us. But at least the meal is over—it was quite substantial, at least in conversation. Let's proceed with other exercises. " The table, once cleared, returned to its slots and grooves, and the piano resumed the place of honor.

Chapter VIII: Which Concerns Music, Ancient and Modern, and the Practical Utilization of Certain Instruments

"So at last, " Michel exclaimed, "we're going to have a little music. "

"But not modern music, " said Jacques. "It's too hard. "

"To understand, yes, " Quinsonnas replied, "but not to make. "

"How's that?" asked Michel.

"I'll explain, " said Quinsonnas, "and I'm going to support what I say with a striking example. Michel, be so good as to open the piano. " The young man obliged. "Good. Now, sit down on the keyboard. "

"What? You want me... "

"Sit down, I said. " Michel lowered himself onto the keys of the instrument and produced a jangling clash of sounds. "Do you know what you've just done?" asked the pianist.

"I haven't a clue!"

"Innocent! You've just created modern harmony. "

"Right, " said Jacques.

"Really, that's a perfect chord for our times, and the awful thing about it is that today's scholars take it upon themselves to explain it scientifically! In the past, only certain notes could be sounded together; but they've been reconciled since then, and now they no longer quarrel among themselves—they're too well brought up for such a thing!"

"But the effect is still just as unpleasant, " Jacques put in.

"Well, my friend, we've reached this point by the force of events; in the last century, a certain Richard Wagner, a sort of messiah who has been insufficiently crucified, invented the Music of the Future, and we're still enduring it; in his day, melody was already being suppressed, and he decided it was appropriate to get rid of harmony as well—and the house has remained empty ever since. "

"But, " Michel reflected, "it's as if you were making a painting without drawing or color!"

"Precisely, " replied Quinsonnas. "And now that you've mentioned painting—painting isn't really a French art, it comes to us from Italy and from Germany, and I would suffer less seeing it profaned. But music is the very daughter of our heart..."

"I thought, " said Jacques, "that music started in Italy!"

"A mistake, my son; until the middle of the sixteenth century, French music dominated Europe; the Huguenot Goudimel[18] was Palestrina's teacher, and the oldest as well as the most naive melodies are Gallic. "

"And now we've reached this point, " said Michel.

"Yes, my son; on the pretext that we are following new formulas, a score now consists of only a single phrase—long, loopy, endless. At the Opera, it begins at eight o'clock and ends just before midnight; if it should extend five minutes more, it costs the management a fine and overtime for the house workers. "

"And this happens without protest?"

"My son, music is no longer tasted, it is swallowed! A few artists put up a struggle, among them your father; but since his death, not a single note has been written worthy of that name! Either we endure the nauseating melody of the virgin forest, insipid, confused, indeterminate, or else various harmony rackets are produced, of which you have given us such a touching example by sitting on the piano. "

"Pathetic!" said Michel.

"Horrible!" replied Jacques.

"Also, my friends, " Quinsonnas resumed, "you must have observed what big ears we have!"

"No, " replied Jacques.

"Well then, just compare our ears with those of the ancients and with the ears of the Middle Ages—examine the paintings and statues, measure the results, and you will be astonished! Ears grow in proportion as the human body shrinks: someday the final result will be something to see! Well, my friends, physiologists have been diligent in searching out the cause of this decadence, and it seems that it is music we have to thank for such appendages; we are living in an age of wizened tympanums and distorted hearing. You realize that no one keeps a century of Verdi or Wagner in his ears without that organ's having to pay for it. "

"That Quinsonnas is a terrifying devil, " said Jacques.

"Nonetheless, " Michel replied, "the old masterpieces are still performed at the Opera. "

"I know, " Quinsonnas answered; "there's even some talk of reviving Offenbach's Orpheus in the Underworld with the recitatives Gounod added to that masterpiece, and it's quite possible that the production will even make a little money, on account of the ballet! What our enlightened public requires, my friends, is some dancing! When you think that a monument costing twenty million francs has been erected chiefly to allow some jumping jacks to be maneuvered around the stage.... They've cut Les Huguenots[19] to a single act, and this little curtain-raiser accompanies the fashionable ballets; the dancers' costumes have been made transparent enough to deceive nature herself, and this enlivens our financiers; the Opera, moreover, has become a branch of the Bourse—quite as much screaming goes on there; business is conducted in full voice, and no one bothers much about the music! Between us, I must admit, the execution leaves something to be desired. "

"A great deal to be desired, " Jacques replied. "The singers whinny, cackle, shriek, and bray—anything and everything but sing. A menagerie!"

"As for the orchestra, " Quinsonnas continued, "it has fallen very low since his instrument no longer suffices to feed the instrumentalist! Talk about a trade that's not practical! Ah, if we could use the power wasted on the pedals of a piano for pumping water out of coal mines! If the air escaping from ophicleides could also be used to turn the Catacomb Company's windmills! If the trombone's alternating action could be applied to a mechanical sawmill—oh, then the executants would be rich and many!"

"You're joking, " exclaimed Michel.

"God help me, " replied Quinsonnas quite seriously, "I shouldn't be surprised if some ingenious inventor managed such things one day! The spirit of invention is what is highly developed in France nowadays! It's really the only spirit we have left! And I can tell you it doesn't make conversations very lively! But who dreams of being entertained? Let's bore one another to death! That's our ruling principle today!"

"And you can't see any remedy for it?" Michel asked.

"None, so long as finance and machinery prevail! And it's really machinery that's doing the mischief. "

"Why is that?"

"Because there's this one good thing about finance: at least it can pay for masterpieces, and a man must eat, even if he has genius! The Genoese, the Venetians, the Florentines under Lorenzo the Magnificent, bankers and businessmen as they were, all encouraged the arts! But mechanics, engineers, technicians—devil take me if Raphael, Titian, Veronese, and Leonardo could ever have come into being! They'd have had to compete with mechanical procedures, and they'd have starved to death! Ah, machinery! It's enough to make you loathe inventors and inventions alike!"

"But after all, " said Michel, "you're a musician, Quinsonnas, you work! You spend your nights at your piano—do you refuse to play modern music?"

"Oh, me! I play as much of it as anyone else—here's a piece I've just written that will appeal to today's taste; it may even have some success, if it finds a publisher. "

"What are you calling it?"

"After Thilorier[20]—a Grand Fantasy on the Liquefaction of Carbonic Acid."

"You can't be serious!" Michel exclaimed.

"Listen and judge for yourselves, " Quinsonnas replied. He sat down at the piano, or rather he flung himself at it. Under his fingers, under his hands, under his elbows, the wretched instrument produced impossible sounds; notes collided and crackled like hailstones. No melody, no rhythm! The artist had undertaken to portray the final experiment which had cost Thilorier his life.

"There!" he exclaimed. "Did you hear that? Now do you understand? Are you aware of the great chemist's experiment? Have you been taken into his laboratory? Do you feel how the carbonic acid is separated out? Here we have a pressure of four hundred ninety-five atmospheres! The cylinder is turning- watch out! watch out! The machine is going to explode! Take cover!" And with a blow of his fist capable of splintering the ivory keys, Quinsonnas reproduced the explosion. "Whew!" he said, "isn't that imitative enough—isn't that beautiful?"

Michel remained stupefied. Jacques couldn't help laughing.

"And you expect a lot from a piece like that, " he said.

"Expect a lot!" Quinsonnas replied. "It's of my time—everyone's a chemist nowadays. I'll be understood. Only it isn't enough to have ideas, there must be proper execution. "

"What do you mean?" asked Jacques.

"Just what I said. It's by execution that I plan to astound the age. "

"But it sounds to me, " Michel argued, "as if you played that piece wonderfully. "

"Don't be ridiculous, " said the artist with a shrug of his shoulders. "I haven't mastered the first note, though I've been studying the cursed thing for three years!"

"What more do you want to do with it?"

"That's my secret, my children; don't ask me to share it with you, you'd only think I was mad, and that would discourage me. But I can assure you that one day the talents of Liszt and Thalberg[21], of Prudent and of Schulhoff[22], will be exposed for what they are. "

"You mean you want to play three more notes per second than they do?" asked Jacques.

"No, but I'll be playing the piano in a new way, a way that will amaze the public! How? I can't tell you.

One allusion, one indiscretion, and someone will steal my idea from me. The vile pack of imitators will be on my heels, and I want to be unique. But that requires superhuman labor! When I'm sure of myself my fortune will be made, and I'll say farewell to Bookkeeping forever!"

"I really think you must be mad, " said Jacques.

"No, not mad, merely maniacal, which is what you must be in order to succeed! But let's get back to some gentler feelings and try to revive a little of that charming past for which we were born too late. Here, my friends, is truth in music!"

Quinsonnas was a great artist; he played with profound feeling, and he knew everything the preceding centuries had bequeathed to his own, which refused the legacy! He took the art at its birth, passing rapidly from master to master, and by his rather rough but sympathetic voice completed what his fingers' execution lacked. He passed in review before his delighted friends the whole history of music, from Rameau and Lully to Mozart and on to Beethoven and Weber, illustrating all the founders of the art, weeping with the gentle inspirations of Grétry, and triumphing in the splendid pages of Rossini a

nd Meyerbeer. "Listen!" he said, "here are the forgotten songs of Guillaume Tell[23], of Robert le Diable[24], of Les Huguenots; here is the charming period of Hérold[25] and Auber[26], two learned men who did themselves honor by knowing nothing! Ah, what has knowledge to do with music? Has it any access to painting? No, and painting and music are all one! That is how people understood this great art during the first half of the nineteenth century! They didn't search out new formulas—there's nothing new to find in music, any more than in love. It remains the charming prerogative of the sensuous arts to be eternally young!"

"Bravo!" cried Jacques.

"But then, " the pianist continued, "certain ambitious natures felt the need to follow new and unknown paths, and they have dragged music after them... into the abyss!"

"Are you saying, " Michel asked, "that you no longer count a single composer after Meyerbeer and Rossini as a true musician?"

"Not at all!" answered Quinsonnas, boldly modulating from D natural to E flat; "I'm not talking about Berlioz, leader of that impotent troupe whose musical ideas were packaged in envious feuilletons; but here are some of the heirs of the great masters: listen to Félicien David[27], a specialist whom our contemporary experts take for King David, first harpist of the Hebrews! Savor those true and simple inspirations of Massé[28], the last musician of heart and feeling, who in his Indienne has given us the masterpiece of his period! Then there's Gounod, the splendid composer of Faust who died soon after having taken orders in the Wagnerian church. And then Verdi, the man of harmonic noise, the hero of musical racket, who made wholesale melody the way certain writers of the period made wholesale literature—Verdi, creator of the inexhaustible Trovatore, who played his singular part in distorting the century's taste...

Enfin Wagnerbe vint... "[29]

At this moment, Quinsonnas let his fingers, no longer constrained by any recognizable rhythm, wander into the incomprehensible reveries of Contemplative Music, proceeding by abrupt intervals and disappearing into the midst of an endless phrase.

With incomparable talent the artist had evidenced the successive gradations of his art; two hundred years of music had just passed beneath his fingers, and his friends listened to him, mute and marveling. Suddenly, in the midst of a powerful elucubration on the Wagnerian school, at the moment when thought was vanishing, dismayed, with no hope of returning to its true path, when sounds gradually gave way to noises whose musical value was no longer appreciable—suddenly a simple, melodic piece, of gentle character and perfectly apt feeling, began to sing beneath the pianist's fingers. This was the calm after the storm, the heart's true note after so much wailing and roaring.

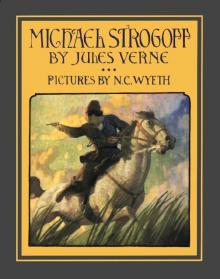

Michael Strogoff; Or the Courier of the Czar: A Literary Classic

Michael Strogoff; Or the Courier of the Czar: A Literary Classic Voyage au centre de la terre. English

Voyage au centre de la terre. English Journey Through the Impossible

Journey Through the Impossible The Castaways of the Flag

The Castaways of the Flag L'île mystérieuse. English

L'île mystérieuse. English Maître du monde. English

Maître du monde. English Around the World in Eighty Days

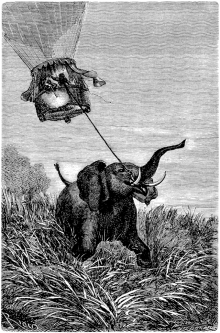

Around the World in Eighty Days A Voyage in a Balloon

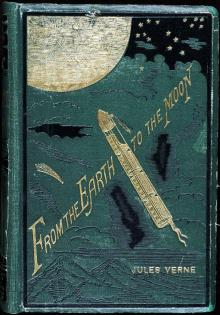

A Voyage in a Balloon From the Earth to the Moon, Direct in Ninety-Seven Hours and Twenty Minutes: and a Trip Round It

From the Earth to the Moon, Direct in Ninety-Seven Hours and Twenty Minutes: and a Trip Round It Paris in the Twentieth Century

Paris in the Twentieth Century City in the Sahara - Barsac Mission 02

City in the Sahara - Barsac Mission 02 The English at the North Pole

The English at the North Pole The Field of Ice

The Field of Ice From the Earth to the Moon

From the Earth to the Moon Un capitaine de quinze ans. English

Un capitaine de quinze ans. English The Mysterious Island

The Mysterious Island Les indes-noirs. English

Les indes-noirs. English Robur-le-conquerant. English

Robur-le-conquerant. English Propeller Island

Propeller Island Around the World in Eighty Days. Junior Deluxe Edition

Around the World in Eighty Days. Junior Deluxe Edition Les forceurs de blocus. English

Les forceurs de blocus. English In the Year 2889

In the Year 2889 Journey to the Centre of the Earth

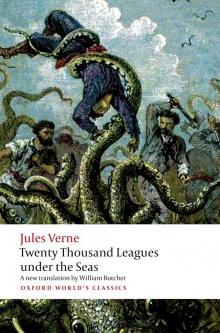

Journey to the Centre of the Earth Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea From the Earth to the Moon; and, Round the Moon

From the Earth to the Moon; and, Round the Moon Vingt mille lieues sous les mers. English

Vingt mille lieues sous les mers. English Cinq semaines en ballon. English

Cinq semaines en ballon. English Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas

Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas Face au drapeau. English

Face au drapeau. English Michael Strogoff; Or, The Courier of the Czar

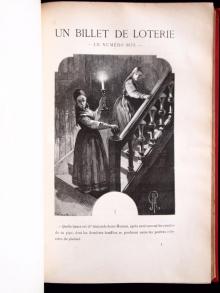

Michael Strogoff; Or, The Courier of the Czar Un billet de loterie. English

Un billet de loterie. English The Secret of the Island

The Secret of the Island Off on a Comet! a Journey through Planetary Space

Off on a Comet! a Journey through Planetary Space Into the Niger Bend: Barsac Mission, Part 1

Into the Niger Bend: Barsac Mission, Part 1 All Around the Moon

All Around the Moon A Journey to the Center of the Earth - Jules Verne: Annotated

A Journey to the Center of the Earth - Jules Verne: Annotated 20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 2

20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 2 Robur-le-Conquerant

Robur-le-Conquerant Les Index Noires

Les Index Noires Michael Strogoff; or the Courier of the Czar

Michael Strogoff; or the Courier of the Czar 20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 1

20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 1 Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Five Weeks In A Balloon

Five Weeks In A Balloon Journey to the Center of the Earth

Journey to the Center of the Earth 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday

Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday The Collected Works of Jules Verne: 36 Novels and Short Stories (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics)

The Collected Works of Jules Verne: 36 Novels and Short Stories (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics) The Survivors of the Chancellor

The Survivors of the Chancellor Their Island Home

Their Island Home Le Chateau des Carpathes

Le Chateau des Carpathes Les Cinq Cents Millions de la Begum

Les Cinq Cents Millions de la Begum The Floating Island

The Floating Island Cinq Semaines En Ballon

Cinq Semaines En Ballon Autour de la Lune

Autour de la Lune