- Home

- Jules Verne

Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday Page 8

Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday Read online

Page 8

Like Fan they heard not the barking close by, which ought to have been the barking of the jackal, or the more distant growling which was probably that of wild beasts. In these countries where ostriches live in a wild state they might expect the approach of jaguars and cougars, which are the tiger and lion of South America. But the night passed without adventure.

About four o’clock in the morning, just as the dawn was showing on the horizon above the lake, the dog began to give signs of uneasiness, growling gently, and sniffing the ground as if she wanted to be sent off in search of something.

It was nearly seven o’clock when Briant awoke his comrades. All were up immediately, and while Service nibbled a bit of biscuit, the three others went to take a look round the country beyond the watercourse.

‘Well,’ exclaimed Wilcox, ‘it is a good thing we didn’t try to cross the water yesterday. We should have stuck in the marsh.’

‘Yes.’ said Briant,’ it is a marsh, and it stretches right away to the south, and we cannot see the end of it.’

‘Just look at the ducks,’ said Donagan, ‘and teal and snipe on it! If we could take up our quarters here for the winter, we should not want for game.’

‘And why shouldn’t we?’ asked Briant, walking towards the right bank of the stream.

At the back was a lofty cliff which ended in a peak. The two sides joined at an angle, one ran by the bank of the river, the other skirted the lake. Was this cliff the same as that which shut in the bay where the schooner was wrecked? That could not be ascertained for certain until a more complete exploration of the district had been made.

The right bank of the river was about twenty feet high, and ran along the base of the cliff, the left bank was very low, and could scarcely be distinguished from the pools and bogs of the marshy plain which extended out of sight towards the south. To make out the direction of the river they would have to ascend the cliff, and this Briant resolved to do before starting for the wreck.

The first thing was to take a look round the outlet of the stream from the lake. This was only about forty feet across, but as it increased in width, so did it increase in depth.

‘Just look here!’ said Wilcox, as he reached the end of the cliff.

A pile of stones attracted his attention, forming a sort of dam on the same plan as the one they had seen in the forest.

‘There is no doubt this time,’ said Briant.

‘No! there is no doubt,’ remarked Donagan, pointing to some pieces of wood at the end of the dam.

The remains were obviously those of a boat of some sort. One piece half rotten and covered with moss, and curved like a stem, held an iron ring eaten away with rust.

‘A ring! a ring!’ exclaimed Service.

And the four stood still, looking around them as if the man who had used the boat and built the dam was about to appear before them.

But nobody came! Many years had evidently gone by since the boat had been left to rot by the side of the stream, and the man had rejoined his fellows or ended his miserable existence on this land he could not leave; and we can understand how the boys felt at this clear evidence of human intervention and the thoughts it gave rise to.

Meanwhile Fan had been behaving in a strange manner, as if she had at last got on a scent. Her ears were pricked up, her tail wagged, and her nose was held close to the ground, as she worried about under the bushes.

‘Look at Fan,’ said Service.

‘She smells something,’ said Donagan, stepping towards her.

Fan had just stopped with one paw raised and her neck stretched out. Then she suddenly rushed towards a clump of trees at the foot of the cliff by the side of the lake.

Briant and his comrades followed her. A few minutes afterwards they stopped before an old beech on the bark of which were cut two letters and a date in this fashion:

F. B.

1827.

Briant, Donagan, Wilcox, and Service would have remained silent and motionless for some time before this inscription if Fan had not run back round the angle of the cliff.

‘Here, Fan! here!’ shouted Briant.

The dog did not return, but she began to bark loudly.

‘Take care,’ said Briant ‘Do not separate, and be on your guard.’

Indeed they could not be too careful. A band of savages might be in the neighbourhood, and their presence was more to be feared than wished for, if they were of those Indians who infest the pampas of South America.

The guns were cocked, and the revolvers got out ready for the defensive. The boys advanced round the angle of the cliff, and up the narrow bank of the stream. They had not taken a dozen paces before Donagan stooped to pick up something from the ground. It was a pickaxe with the handle half rotten—a pickaxe of American or European origin, not one of those heavy tools made by the Polynesian savages. Like the ring on the boat it was deeply rusted, and must have been left behind many years ago.

At the foot of the cliff were traces of tillage, a few irregular furrows, a little square of yams, which left to themselves had run wild.

Suddenly a mournful bark was heard, and Fan reappeared, seized with some inexplicable agitation. She turned round, she ran in front of her masters, looked back at them, called them, and seemed to invite them to follow.

‘There is certainly something extraordinary the matter,’ said Briant, trying in vain to get the dog quiet.

‘Let us go where she is taking us to,’ said Donagan, making a sign to Wilcox and Service to follow.

Ten yards further on Fan stood up before a mass of brushwood and bushes, which reached up to the very foot of the cliff.

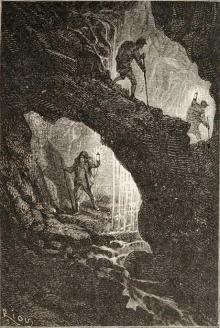

Briant looked to see if the bushes hid the corpse of some animal, or even of a man on whose traces Fan had fallen. Clearing away the bushes, he saw a narrow opening.

‘Is there a cave here?’ he exclaimed, stepping back a few paces.

‘Likely enough,’ said Donagan. ‘But what is there in the cave?’

‘We will see,’ answered Briant.

And with his hatchet he began to cut away the entanglement about the entrance. He listened, but heard no suspicious noise.

Service was about to slip through into the cave, when Briant stopped him.

‘See what Fan is going to do first.’

The dog barked angrily twice or thrice in a way that was anything but reassuring for a person in the cave, had one been there.

What did it mean? The boys must find out. Briant put a handful of dry twigs across the opening and lighted them to see if the air was foul. The twigs crackled and burnt brilliantly: evidently the air was breathable.

‘Shall we go in?’ asked Wilcox.

‘Yes,’ said Donagan.

‘Wait till we can see our way’ said Briant. And cutting a resinous branch from one of the pine-trees close by, he lighted it. Then followed by his companions he stepped into the cave.

The opening was about four feet high and two feet wide; but it grew larger immediately, forming a cavity twelve feet high and twice as wide, with a floor of hard, dry sand.

As he hurried to the front Wilcox stumbled over a wooden bench, near a table on which were certain domestic utensils, a jug of stoneware, some large shells that had been used as plates, a knife with a notched and rusty blade, two or three fish-hooks, a tin cup, empty like the jug. Near the opposite wall was a sort of box, made of planks roughly nailed together, and which contained a few tattered clothes.

There could be no doubt that the excavation had been inhabited. But when, and by whom? What had become of the human being who had lived here?

At the end was a miserable pallet covered with some fragments of linen. At the head, on a bench, was a second cup, and a wooden candlestick, with only a burnt match on the bowl.

The boys recoiled from the pallet, at first thinking it might hold a corpse.

Briant repressing his repugnance, lifted up the covering.

The pallet was empty.

A minute afterwards, the boys, who were much affected, had

rejoined Fan, who still kept up her mournful barking.

They descended the bank of the stream for about twenty yards, and suddenly stopped. A feeling of horror nailed them to the spot.

There, among the roots of a beech-tree, were the remains of a skeleton.

And so to this place there had come to die the unhappy man who had lived on this continent, and the cave that had been his dwelling-place had not been his tomb.

CHAPTER IX—FRANÇOIS BAUDOIN.

THE boys were silent. Who was this man who had come to die here? Was he a shipwrecked sailor to whom no help had come in his last hour? To what nation did he belong? Was he a young man when he arrived in this corner of the earth? Was he an old man when he died? How had he supplied his wants? If he had been shipwrecked, had others survived the catastrophe with him? And if so, had he remained alone after the death of his companions in misfortune? Did the different things in the cave belong to his ship, or had he made them with his own hands? But to such questionings no answer might ever be given.

And here was a more serious one! If it was on a continent that this man had found refuge, why had he not reached some town in the interior, or some port on the shore? Were there such difficulties, such obstacles in his getting back to his own country that he could not overcome them? Was the distance so great that he thought he could not accomplish it? It was evident that he had fallen down, weak from sickness or old age, and had not had strength enough to regain the cave, but had died at the foot of the tree! And if the means of safety to the north and east had failed him, why should they not fail these boys from the wreck of the schooner?

It was important to examine the cave with the greatest care. Who knew if they might not find a document which might throw some light on this man, or his birthplace, or the length of the stay! And on the other hand it was advisable to ascertain if they could take up their quarters here for the winter after abandoning the wreck.

‘Come!’ said Briant.

And, followed by Fan, they entered the cave by the light of another resinous torch.

One of the first things they saw was a shelf fixed against the right wall, on which was a bundle of clumsy candles made of fat and tow. Service lighted one of these candles, and placed it in the wooden candlestick, and the search began.

In the first place the shape of the cave was noted, for there was no doubt of its habitability. It was a large hollow, dating back from geologic times. There was no trace or damp, although the only ventilation was through the one opening on to the bank of the stream. The walls were as dry as if they were of granite, without any trace of crystallized infiltrations and strings of droplets which in certain grottoes of porphyry or basalt form stalactites. Its position sheltered it from the sea breezes. Daylight penetrated it but little, it is true, but by opening one or two windows in the wall it would be easy to make this right, and to ventilate it sufficiently for the accommodation of fifteen people.

Its dimensions—twenty feet by thirty feet—made it too small to be used at the same time as dormitory, refectory, general store, and kitchen. But it would only be required for five or six months, after which a start could be made to the north-east for some town of Bolivia or the Argentine Republic. Evidently, if they had to take up their permanent abode here, the cave would have to be made larger by digging into the friable limestone. But the cave as it was would do very well till the summer season.

This being ascertained, Briant made a careful list of the things it contained. These were not many. The unfortunate man had been almost destitute. What had he secured from the wreck? Nothing but odds and ends, broken spars, pieces of plank that he had made up into the pallet, the table, the box, and the benches, which formed the only furniture. Less favoured than the survivors of the schooner, he had not had a regular workshop ready at hand. A few tools, a pickaxe, an axe, two or three cooking utensils, a little cask of brandy, a hammer, two cold chisels, a saw—these were all that were found. They had been saved doubtless in the boat, the remains of which lay near the dam.

So thought Briant, and so he told his companions. And then the feeling of horror at the sight of the skeleton, and the thought that they might die abandoned in the same way, gave place to a feeling of confidence at their possession of so many things which to this man were wanting.

But who was he? Where was he born? When was he wrecked? No doubt many years had passed since his death. The state of the bones found at the foot of the tree showed that only too well! Besides, there was the rust on the pickaxe and the ring, the thicket of bushes at the entrance of the cave all tending to show that the man must have died years ago. Would any new discovery change this hypothesis into a certainty?

The search continued. A few other objects were brought to light—a second knife with the blades broken, a pair of compasses, a kettle, an iron ring, a marline-spike. But there was no nautical instrument, no telescope, no mariner’s compass, not even a musket.

As the man had to live, it seemed as though he must have snared his food instead of shot it But an explanation of the difficulty offered itself when Wilcox exclaimed, —

‘What is that?’

‘That?’ answered Service.

‘It is a game at bowls,’ said Wilcox.

‘A game at bowls?’ asked Briant in surprise. But in a moment he recognized the use of the two round stones which Wilcox had picked up. It was one of those implements of the chase, known as the bolas. which consists of two balls tied together with a cord, and is used by the Indians of South America. When a skilful hand throws the bolas, they encircle the limbs of the animal, and for a moment paralyze it so that it falls an easy prey to the hunter.

Evidently the inhabitant of the cave had made this bolas, and also a lasso, a long loop of leather used at shorter distances.

But who was this man? Was he an officer or a common seaman who had put his reading to profit in this way? It would be very difficult to discover without further discovery.

At the head of the bed, under a rag of the clothes that Briant had thrown aside, Wilcox found a watch hung on a nail fixed in the wall.

This watch was not a common watch such as sailors usually wear, but was of finer workmanship, and had a double case of silver and a key and chain of the same metal.

‘The time! See the time!’ said Service.

‘The time will tell you nothing,’ said Briant ‘The watch probably stopped days before the unfortunate man died.’

Briant opened the case, not without difficulty, for the hinges were rusty, and he saw that the hands pointed to twenty-seven minutes past three.

‘But,’ said Donagan, ‘the watch has the maker’s name. That might tell us—’

‘You are right,’ said Briant

And looking inside the case, he managed to read these words engraved on the plate: —

‘Delpeuch, Saint Malo?

The name of the maker and his address.

‘Then he was a Frenchman!’ exclaimed Briant.

There seemed little doubt that a Frenchman had lived in this cavern until death put an end to his misery.

To this proof another was soon added when Donagan, who had turned over the pallet, found a note-book with its yellow pages covered with pencil writing.

Unfortunately most of the writing was illegible. A few words could, however, be deciphered, and among others were—François Baudoin.

Two names, the initials of which were the same as those the man had cut on the tree. The note-book was the daily journal of his life from the day he had been cast ashore. And in the fragments of phrases that time had not entirely effaced Briant managed to read Duguay Trouin, evidently the name of the ship that had been lost in this distant corner of the Pacific.

At the commencement was a date 1827—the same as that which had been cut under the initials on the tree.

It was, then, fifty-five years since François Baudoin had been thrown on this coast; and since his shipwreck he had received no help from without. If Francis Baudoin had not moved to some other pl

ace on the continent, was it because the obstacles were insurmountable?

More than ever the boys thought of the gravity of their situation. How could they do what this man had not done, a man accustomed to hard work, and broken to fatigue?

Another discovery was to show them that all attempts to leave the country would be in vain.

As Donagan turned over the note-book he found a folded paper between the leaves. It was a map, drawn in ink made probably of soot and water.

‘A map!’ he exclaimed.

‘Which François Baudoin has drawn with his own hand!’ said Briant.

‘If that is so,’ said Wilcox, ‘the man could not be a common sailor, but one of the officers of the Duguay Trouin. To make a map of this place—’

‘And that is what it is,’ said Donagan.

There could be no mistake. At the first glance the boys recognized the bay of the wreck, the bank of reefs, the beach on which they had encamped, the lake they had skirted on the western side, the three islands in the offing, the cliff running along to the stream, and the forests covering the central region.

Beyond the opposite bank of the lake were other forests extending to another shore, and that shore the sea washed on all sides!

There was an end to all the plans of going eastward to seek safety in that direction! And so Briant was right after all, and Donagan was wrong. The sea surrounded the imaginary continent on every side. It was an island, and that was why Francis Baudoin could not leave it.

It was easy to see that the map was correct. The distances were probably mere estimates, from the times taken to traverse them, and not arrived at by triangulation; but to judge by what was already known, the errors could not be important.

It was clear that the shipwrecked man had been all over the island, that he had noted the chief geographical details, and probably the ajoupa and the causeway at the creek were of his building.

Michael Strogoff; Or the Courier of the Czar: A Literary Classic

Michael Strogoff; Or the Courier of the Czar: A Literary Classic Voyage au centre de la terre. English

Voyage au centre de la terre. English Journey Through the Impossible

Journey Through the Impossible The Castaways of the Flag

The Castaways of the Flag L'île mystérieuse. English

L'île mystérieuse. English Maître du monde. English

Maître du monde. English Around the World in Eighty Days

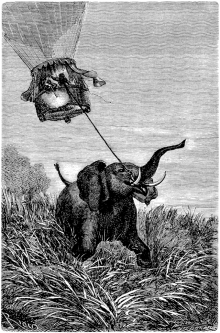

Around the World in Eighty Days A Voyage in a Balloon

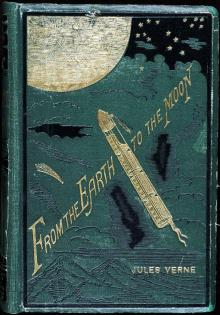

A Voyage in a Balloon From the Earth to the Moon, Direct in Ninety-Seven Hours and Twenty Minutes: and a Trip Round It

From the Earth to the Moon, Direct in Ninety-Seven Hours and Twenty Minutes: and a Trip Round It Paris in the Twentieth Century

Paris in the Twentieth Century City in the Sahara - Barsac Mission 02

City in the Sahara - Barsac Mission 02 The English at the North Pole

The English at the North Pole The Field of Ice

The Field of Ice From the Earth to the Moon

From the Earth to the Moon Un capitaine de quinze ans. English

Un capitaine de quinze ans. English The Mysterious Island

The Mysterious Island Les indes-noirs. English

Les indes-noirs. English Robur-le-conquerant. English

Robur-le-conquerant. English Propeller Island

Propeller Island Around the World in Eighty Days. Junior Deluxe Edition

Around the World in Eighty Days. Junior Deluxe Edition Les forceurs de blocus. English

Les forceurs de blocus. English In the Year 2889

In the Year 2889 Journey to the Centre of the Earth

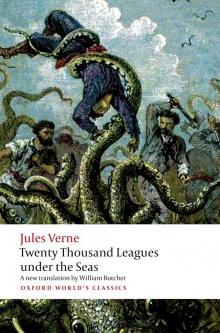

Journey to the Centre of the Earth Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea From the Earth to the Moon; and, Round the Moon

From the Earth to the Moon; and, Round the Moon Vingt mille lieues sous les mers. English

Vingt mille lieues sous les mers. English Cinq semaines en ballon. English

Cinq semaines en ballon. English Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas

Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas Face au drapeau. English

Face au drapeau. English Michael Strogoff; Or, The Courier of the Czar

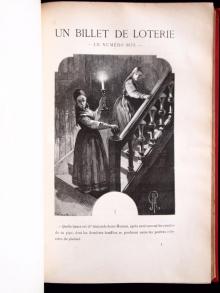

Michael Strogoff; Or, The Courier of the Czar Un billet de loterie. English

Un billet de loterie. English The Secret of the Island

The Secret of the Island Off on a Comet! a Journey through Planetary Space

Off on a Comet! a Journey through Planetary Space Into the Niger Bend: Barsac Mission, Part 1

Into the Niger Bend: Barsac Mission, Part 1 All Around the Moon

All Around the Moon A Journey to the Center of the Earth - Jules Verne: Annotated

A Journey to the Center of the Earth - Jules Verne: Annotated 20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 2

20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 2 Robur-le-Conquerant

Robur-le-Conquerant Les Index Noires

Les Index Noires Michael Strogoff; or the Courier of the Czar

Michael Strogoff; or the Courier of the Czar 20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 1

20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 1 Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Five Weeks In A Balloon

Five Weeks In A Balloon Journey to the Center of the Earth

Journey to the Center of the Earth 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday

Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday The Collected Works of Jules Verne: 36 Novels and Short Stories (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics)

The Collected Works of Jules Verne: 36 Novels and Short Stories (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics) The Survivors of the Chancellor

The Survivors of the Chancellor Their Island Home

Their Island Home Le Chateau des Carpathes

Le Chateau des Carpathes Les Cinq Cents Millions de la Begum

Les Cinq Cents Millions de la Begum The Floating Island

The Floating Island Cinq Semaines En Ballon

Cinq Semaines En Ballon Autour de la Lune

Autour de la Lune