- Home

- Jules Verne

The Castaways of the Flag Page 9

The Castaways of the Flag Read online

Page 9

A new reason for alarm would have been added if all had known what only Captain Gould and the boatswain knew—that the number of turtles was decreasing perceptibly, in consequence of their daily consumption!

"But perhaps," John Block suggested, "it is because the creatures know of some passage underground through which they can get to the creeks to the east and west; it is a pity we can't follow them."

"Anyhow, Block," Captain Gould replied, "don't say a word to our friends."

"Keep your mind easy, captain. I told you because one can tell you everything.''

"And ought to tell me everything, Block!"

Thereafter the boatswain was obliged to fish more assiduously, for the sea would never withhold what the land would soon deny. Of course, if they lived exclusively on fish and molluscs and crustaceans, the general health would suffer. And if illness broke out, that would be the last straw.

The last week of December came. The weather was still fine, except for a few thunderstorms, not so violent as the first one. The heat, sometimes excessive, would have been almost intolerable but for the great shadow thrown over the shore by the cliff, which sheltered it from the sun as it traced its daily arc above the northern horizon.

At this season numbers of birds thronged these waters—not only sea-gulls and divers, sea-mew and frigate birds, which were the usual dwellers on the shore. From time to time flocks of cranes and herons passed, reminding Fritz of his excellent sport round Swan Lake and about the farms in the Promised Land. On the top of the bluff, too, cormorants appeared, like Jenny's bird, now in the poultry-run at Rock Castle, and albatrosses like the one she had sent with her message from the Burning Rock.

These birds kept out of range. When they settled on the promontory it was useless to attempt to get near them, and they flew at full speed above the inaccessible crest of the cliff.

One day all the others were called to the beach by a shout from the boatswain.

"Look there! Look there!" he continued to cry, pointing to the edge of the upper plateau.

"What is it?" Fritz demanded.

"Can't you see that row of black specks?" John Block returned.

"They are penguins," Frank replied.

"Yes, they are penguins," Captain Gould declared; "they look no bigger than crows, but that is because they are perched so high up."

"Well," said Fritz, "if those birds have been able to get up on to the plateau, it means that on the other side of the cliff the ascent is practicable."

That seemed certain, for penguins are clumsy, heavy birds, with rudimentary stumps instead of wings. They could not have flown up to the crest. So if the ascent could not be made on the south, it could be on the north. But from lack of a boat in which to go along the shore this hope of reaching the top of the cliff had to be abandoned.

Sad, terribly sad, was the Christmas of this most gloomy year! Full of bitterness was the thought of what Christmas might have been in the large hall of Rock Castle, in the midst of the two families, with Captain Gould and John Block.

Yet, in spite of all these trials, the health of the little company was not as yet affected. On the boatswain hardship had no more effect than disappointment.

"I am getting fat," he often said; "yes, I am getting fat! That's what comes of spending one's time doing nothing!"

Doing nothing, alas! Unhappily, in the present situation, there was practically nothing to do!

In the afternoon of the 29th something happened which recalled memories of happier days.

A bird settled on a part of the promontory which was not inaccessible.

It was an albatross, which had probably come a long way, and seemed to be very tired. It lay out on a rock, its legs stretched, its wings folded.

Fritz determined to try to capture this bird. He was clever with the lasso, and he thought he might succeed if he made a running noose with one of the boat's halyards.

A long line was prepared by the boatswain, and Fritz climbed up the promontory as softly as possible.

Everybody watched him.

The bird did not move and Fritz, getting within a few fathoms of it, cast his lasso round its body.

The bird made hardly any attempt to get free when Fritz, who had picked it up in his arms, brought it down to the beach.

Jenny could not restrain a cry of astonishment.

"It is! It is!" she exclaimed, caressing the bird. '' I am sure I recognise him!''

"What?" Fritz exclaimed; "you mean –"

"Yes, Fritz, yes! It really is my albatross; my companion on Burning Rock; the one to which I tied the note that fell into your hands.''

Could it be? Was not Jenny mistaken? After three whole years, could that same albatross, which had never returned to the island, have flown to this coast?

But Jenny was not mistaken, and all were made quite sure about it when she showed them a little bit of thread still fastened round one of the bird's claws. Of the scrap of cloth on which Fritz had traced his few words of reply, nothing now remained.

If the albatross had come from so far, it was no doubt because these powerful birds can fly vast distances. Quite likely this one had come from the east of the Indian Ocean to these regions of the Pacific possibly more than a thousand miles away!

Much petting was lavished upon the messenger from Burning Rock. It was like a link between the shipwrecked people and their friends in New Switzerland.

Two days later the year 1817 reached its end.

What did the new year hold in store?

CHAPTER VIII - LITTLE BOB LOST

IF Captain Gould was not mistaken in his calculations about the geographical position of the island, the summer season could not have more than another three months to run. After that, winter would arrive, formidable by reason of its cold squalls and furious storms. The faint chance of attracting the attention of some ship out at sea by means of signals would have disappeared. In winter sailors avoid these dangerous waters. But just possibly something would happen before then to modify the situation.

Existence was much what it had been ever since that gloomy 26th of October when the boat was destroyed. The monotony was terribly trying to such active men. With nothing to do but wander about at the foot of the cliff which imprisoned them, tiring their eyes with watching the ever deserted sea, they needed extraordinary moral courage not to give way to despair.

The long, long days were spent in conversation in which Jenny bore the principal part.

The brave young woman loved them all, taxed her ingenuity to keep their minds occupied, and discussed all manner of schemes, as to the utility of which she herself was under no misapprehension.

Sometimes they wondered if the island really lay, as they had supposed, in the west of the Pacific. The boatswain expressed some doubt on this point.

"Is it the albatross's coming that has changed your mind?" the captain asked him one day.

"Well, yes, it has," John Block replied; "and I am right, I think."

"You infer from it that this island lies farther north than we supposed, Block?"

"Yes, captain; and, for all anybody knows, somewhere near the Indian Ocean. An albatross might fly hundreds of miles without resting, but hardly thousands."

"I know that," Captain Gould replied, "but I know, too, that it was to Borupt's interest to take the Flag towards the Pacific! As for the week we were shut up in the hold, I thought, and so did you, that the wind was from the west."

"I agree," the boatswain answered, "and yet, this albatross –, Has it come from near, or from far?"

"And even supposing you are right, Block, even supposing we were mistaken about the position of this island, and that it really is only a few miles from New Switzerland, isn't that just as bad as if it were hundreds of miles off, seeing that we can't get away from it?"

Captain Gould's conclusion was unfortunately only too reasonable. Everything pointed to the probability of the Flag having steered for the Pacific, far, very far, from New Switzerland's waters. And ye

t what John Block was thinking, others were thinking too. It seemed as if the bird from Burning Rock had brought hope with it.

When the bird recovered from its exhaustion, which it speedily did, it was neither timid nor wild. It was soon walking about the beach, feeding on the berries of the kelp or on fish, which it was very clever in catching, and it showed no desire to fly away.

Sometimes it would fly along the promontory and settle on the top of the cliff, uttering little cries.

"Ah, ha!" the boatswain used to say then. '' He is asking us up! If only he could give me the loan of his wings I would willingly undertake to fly up there, and look over the other side. Very likely that side of the coast isn't any better than this one, but at any rate we would know."

Know? Did they not know already, since Fritz had seen nothing but the same arid rocks and the same inaccessible heights beyond the bluff?

One of the albatross's chief friends was little Bob. A comradeship had promptly been established between the child and the bird. They played together on the sand. There was no danger to be apprehended from the teasing of the one or the pecking of the other. When the weather was bad both went into the cave where the albatross had his own corner.

Serious thought had to be given to the chances of a winter here. But for some stroke of good fortune they would have to endure four or five months of bad weather. In these latitudes, in the heart of the Pacific, storms burst with extraordinary violence, and lower the temperature to a serious extent.

Captain Gould, Fritz, and John Block talked sometimes of this. It was better to look the perils of the future squarely in the face. Having made up their minds to struggle on, they no longer felt the discouragement which had been caused earlier by the destruction of the boat.

"If only the situation were not aggravated by the presence of the women and the child," Captain Gould said more than once, "if we were only men here –"

"All the more reason to do more than we should have done," Fritz rejoined.

One serious question cropped up in these anticipations of the winter: if the cold became severe, and a fire had to be kept up day and night, might not the supply of fuel give out?

Kelp was deposited on the beach by every incoming tide and quickly dried by the sun. But an acrid smoke was produced by the combustion of these sea-weeds, and they could not make use of them to warm the cave. The atmosphere would have been rendered unbearable. So it was thought best to close the entrance with the sails of the boat, fixing them firmly enough to withstand the squalls which beset the cliff during the winter.

There remained the problem of lighting the inside of the cave when the weather should preclude the possibility of working outside.

The boatswain and Frank, assisted by Jenny and Dolly, made many rude candles out of the grease from the dog-fish which swarmed in the creek and were very easy to catch.

John Block melted this grease and so obtained a kind of oil which coagulated as it cooled. Since he had at his disposal none of the cotton grown by M. Zermatt, he was obliged to content himself with the fibre of the laminariae, which furnished practicable wicks.

There was also the question of clothes, and that was a different question indeed.

"It's pretty clear," said the boatswain one day, "that when you are shipwrecked and cast on a desert island it is prudent to have a ship at your disposal in which you can find everything you want. One makes a poor job of it otherwise!''

They all agreed. That was how the Landlord had been the salvation of the people in New Switzerland.

In the afternoon of the 17th an incident of which no one could have foreseen the consequence caused the most intense anxiety.

As already mentioned, Bob found great pleasure in playing with the albatross. When he was amusing himself on the shore his mother kept a constant watch upon him, to see that he did not go far away, for he was fond of scrambling about among the low rocks of the promontory and running away from the waves. But when he stayed with the bird in the cave there was no risk in leaving him by himself.

It was about three o'clock. James Wolston was helping the boatswain to arrange the spars to support the heavy curtain in front of the entrance to the cave. Jenny and Susan and Dolly were sitting in the corner by the stove on which the little kettle was boiling, and were busy mending their clothes.

It was nearly time for Bob's luncheon.

Mrs. Wolston called the child.

Bob did not answer.

Susan went down to the beach and called louder, but still got no reply. Then the boatswain called out: "Bob! Bob! It's dinner time!"

The child did not appear, and he could not be seen running about the shore.

"He was here only a minute ago," James declared.

"Where the deuce can he be?" John Block said to himself, as he went towards the promontory.

Captain Gould, Fritz, and Frank were walking along the foot of the cliff.

Bob was not with them.

The boatswain made a trumpet of his hands and called out several times:

"Bob! Bob!"

The child remained invisible.

James came up to the captain and the two brothers.

"You haven't seen Bob, have you?" he asked in a very anxious voice.

"No," Frank answered.

"I saw him half an hour ago," Fritz declared; "he was playing with the albatross."

And all began to call him, turning in every direction.

It was in vain.

Then Fritz and James went to the promontory, climbed the nearest rocks, and looked all over the creek.

Neither child nor bird was there.

Both went back to the others. Mrs. Wolston was pale with fear.

"Have you looked inside the cave?" Captain Gould asked.

Fritz made one spring to the cave and searched every corner of it, but came back without the child.

Mrs. Wolston was distracted. She went to and fro like a mad woman. The little boy might have slipped among the rocks, or fallen into the sea. The most alarming suppositions were permissible since Bob had not been found.

So the search had to be prosecuted without a moment's delay along the beach and as far as the creek.

"Fritz and James," said Captain Gould, "come with me along the foot of the cliff. Do you think Bob could have got buried in a heap of sea-weed?"

"Yes, you go," said the boatswain, "while Mr. Frank and I go and search the creek."

"And the promontory," Frank added. "It is possible that Bob may have taken it into his head to go climbing there and have fallen into some hole."

So they separated, some going to the right, some to the left. Jenny and Dolly stayed with Mrs. Wolston and tried to allay her anxiety.

Half an hour later, all were back again, after a fruitless search. Nowhere in the bay was any trace of the child, and all their calling had been without result.

Susan's grief broke out. She sobbed in anguish and had to be carried, against her will, into the cave. Her husband, who went with her, could not utter a word. Outside, Frank said:

'' The child can 't possibly be lost! I tell you again, I saw him on the shore scarcely an hour ago, and he was not near the sea. He had a string in his hand, with a pebble at the end of it, and was playing with the albatross."

"By the way, where is the bird?" Frank asked, looking round.

"Yes; where is he?" John Block echoed.

"Can they have disappeared together?" Captain Gould enquired.

"It looks like it," Fritz replied.

They looked in every direction, and especially towards the rocks where the bird was accustomed to perch.

It was not to be seen, nor could its cry be heard—a cry easily distinguishable from the noises of the divers, gulls, and sea-mews.

The albatross might have flown above the cliff and made for some other eminence along the coast. But the little boy could not have flown away. Yet he might have been capable of climbing along the promontory after the bird. This explanation was hardly admissible, howeve

r, after the search that Frank and the boatswain had made.

Yet it was impossible not to see some connection between Bob's disappearance and that of the albatross. They hardly ever separated, and now they were both lost together!

Evening drew on. The father and mother were in terrible grief. Susan was so agitated that they feared for her reason. Jenny, Dolly, Captain Gould and the others, did not know what next to do. When they reflected that if the child had fallen into some hole he would have to stay there all night, they began to search again. A fire of sea-weed was lighted at the far end of the promontory, to be a guide for the child in case he should have gone to the back of the creek. But after remaining afoot until the last possible minute of the evening, they had to give up hope of finding Bob. And what were the chances of their being more successful next day?

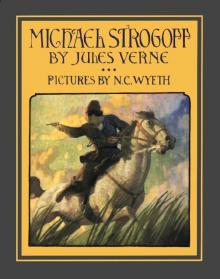

Michael Strogoff; Or the Courier of the Czar: A Literary Classic

Michael Strogoff; Or the Courier of the Czar: A Literary Classic Voyage au centre de la terre. English

Voyage au centre de la terre. English Journey Through the Impossible

Journey Through the Impossible The Castaways of the Flag

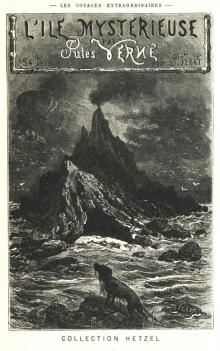

The Castaways of the Flag L'île mystérieuse. English

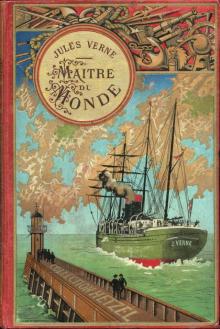

L'île mystérieuse. English Maître du monde. English

Maître du monde. English Around the World in Eighty Days

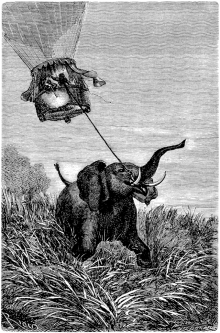

Around the World in Eighty Days A Voyage in a Balloon

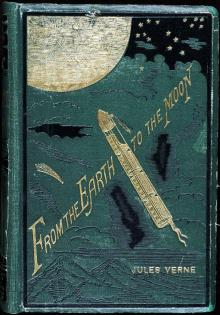

A Voyage in a Balloon From the Earth to the Moon, Direct in Ninety-Seven Hours and Twenty Minutes: and a Trip Round It

From the Earth to the Moon, Direct in Ninety-Seven Hours and Twenty Minutes: and a Trip Round It Paris in the Twentieth Century

Paris in the Twentieth Century City in the Sahara - Barsac Mission 02

City in the Sahara - Barsac Mission 02 The English at the North Pole

The English at the North Pole The Field of Ice

The Field of Ice From the Earth to the Moon

From the Earth to the Moon Un capitaine de quinze ans. English

Un capitaine de quinze ans. English The Mysterious Island

The Mysterious Island Les indes-noirs. English

Les indes-noirs. English Robur-le-conquerant. English

Robur-le-conquerant. English Propeller Island

Propeller Island Around the World in Eighty Days. Junior Deluxe Edition

Around the World in Eighty Days. Junior Deluxe Edition Les forceurs de blocus. English

Les forceurs de blocus. English In the Year 2889

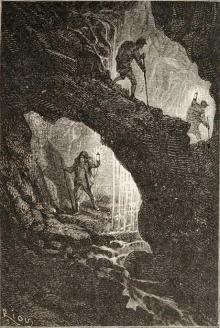

In the Year 2889 Journey to the Centre of the Earth

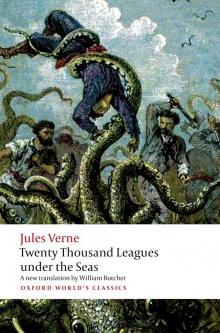

Journey to the Centre of the Earth Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea From the Earth to the Moon; and, Round the Moon

From the Earth to the Moon; and, Round the Moon Vingt mille lieues sous les mers. English

Vingt mille lieues sous les mers. English Cinq semaines en ballon. English

Cinq semaines en ballon. English Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas

Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas Face au drapeau. English

Face au drapeau. English Michael Strogoff; Or, The Courier of the Czar

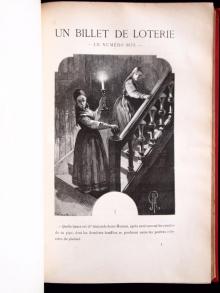

Michael Strogoff; Or, The Courier of the Czar Un billet de loterie. English

Un billet de loterie. English The Secret of the Island

The Secret of the Island Off on a Comet! a Journey through Planetary Space

Off on a Comet! a Journey through Planetary Space Into the Niger Bend: Barsac Mission, Part 1

Into the Niger Bend: Barsac Mission, Part 1 All Around the Moon

All Around the Moon A Journey to the Center of the Earth - Jules Verne: Annotated

A Journey to the Center of the Earth - Jules Verne: Annotated 20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 2

20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 2 Robur-le-Conquerant

Robur-le-Conquerant Les Index Noires

Les Index Noires Michael Strogoff; or the Courier of the Czar

Michael Strogoff; or the Courier of the Czar 20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 1

20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 1 Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Five Weeks In A Balloon

Five Weeks In A Balloon Journey to the Center of the Earth

Journey to the Center of the Earth 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday

Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday The Collected Works of Jules Verne: 36 Novels and Short Stories (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics)

The Collected Works of Jules Verne: 36 Novels and Short Stories (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics) The Survivors of the Chancellor

The Survivors of the Chancellor Their Island Home

Their Island Home Le Chateau des Carpathes

Le Chateau des Carpathes Les Cinq Cents Millions de la Begum

Les Cinq Cents Millions de la Begum The Floating Island

The Floating Island Cinq Semaines En Ballon

Cinq Semaines En Ballon Autour de la Lune

Autour de la Lune