- Home

- Jules Verne

Paris in the Twentieth Century Page 9

Paris in the Twentieth Century Read online

Page 9

"Perhaps a revolution will be made against Progress..."

"Possible, possible, and that would have its amusing aspects. But let's not lose ourselves in such philosophical divagations, Nephew—let's keep on our way through the ranks. Here's a sumptuous commander who spent forty years of his life talking about his modesty: Chateaubriand, and even his Mémoires d'Outre-Tombe haven't been able to save him from oblivion. "

"Isn't that Bernardin de Saint-Pierre beside him? I suspect that sweet novel of his, Paul et Virginie, wouldn't move anyone today. "

"Alas no: Paul would be a banker today, and Virginie would marry the son of a manufacturer of railway tracks. Now here are the famous memoirs of Monsieur de Talleyrand, published, on his orders, thirty years after his death. I'm sure that fellow is still doing diplomacy where he is now, though even Talleyrand won't be able to fool the Devil—for long! Now here's an officer who wielded sword and pen alike, a great Hellenist who wrote in French like a contempo rary of Tacitus: Paul-Louis Courier! When our language is lost, Michel, it can be created all over again out of the works of this proud scribe. Here's kindly Nodier, and with him Béranger[36], a great statesman who wrote his songs in his spare time. And here we have reached that brilliant generation that escaped the Restoration as if it were a seminary, making a great riot in the streets. "

"Lamartine, " said the young man, "a great poet!"

"One of the leaders of our literature of images, a statue of Memnon that sang so beautifully when touched by sunbeams! Poor Lamartine, after lavishing his fortune on the noblest causes and plucking the harp of the poor in the streets of an ungrateful city, wasted his talent on his creditors, delivered his estate of Saint-Point[37] from the cancer of mortgages, and died of grief at seeing that sacred earth where all his family lay expropriated by a railroad company!"

"Poor poet, " Michel echoed.

"Beside his lyre, " resumed Uncle Huguenin, "you'll notice Alfred de Musset's guitar: it's never played nowadays, and you have to be an old amateur like myself to delight in the vibrations of its slack strings. We're in the music section of our army now. "

"Oh, Victor Hugo!" Michel exclaimed. "Uncle, I hope you consider him among our great captains!"

"In the first rank, my boy, bearing the flag of Romanticism on the bridge of Arcole, victor of the battles of Hernani, of Ruy Blas, of the Burgraves, of Marion de Lorme! Like Bonaparte, he was already a general at twenty-five, and defeated the Austrian classics at every encounter. Never, my son, has human thought been brewed more vigorously than in that man's skull, a crucible capable of enduring the highest temperatures known to humanity. I know nothing to exceed him, in antiquity or modern times, for the violence and the richness of imagination. Hugo is the highest personification of the first half of the nineteenth century, and leader of a school which will never be equaled. His complete works have had seventy-five editions, of which this is the last; he is forgotten like the rest, my boy, and hasn't killed enough people to be remembered!"

"Uncle, you have the twenty volumes of Balzac!" exclaimed Michel, standing on a stool.

"Of course I do! Balzac is the first novelist in all the world, and several of his characters have outstripped even Moliére's types. In this day and age, he wouldn't have had the courage to write La Comédie Humaine."

"Even so, he described some terrible behavior, and how many of his heroes are true to life who wouldn't figure badly among us!"

"Probably you're right, " Monsieur Huguenin replied, "but where would he find a de Marsay, a Granville, a Chesnel, a Mirouët, a Du Guénic, a Montriveau, a Chevalier de Valois, a La Chanterie, or women like Madame de Maufrigneuse, Eugénie Grandet, or Pierrette, charming characters of nobility and intelligence and gallantry and charity and candor—these were men and women he copied, not invented! It's true that his misers, the financiers protected by the law, the amnestied thieves would sit for him in great numbers today, and he wouldn't have any difficulty finding a Crevel, a Nuicingen, a Vautrin, a Corentin, or a Gobseck among us!"

"Here's what looks to me, " said Michel, moving on to other shelves, "like a considerable author. "

"Indeed! That is Alexandre Dumas, the Murat of literature, interrupted by death at his nineteen hundred and ninety-third volume! The most entertaining of all storytellers, whom prodigal nature allowed to abuse... everything without doing himself harm—his talent, his intelligence, his verve, his energy, even his physical strength when he took the powder keg of Soissons, his birth, his color, France, Spain, Italy, the banks of the Rhine, Switzerland, Algeria, the Caucasus, Mount Sinai, and Naples, especially when he forced entry on the Spéronare! What an astonishing personality! It's believed he would have reached his two thousandth volume if he hadn't been poisoned in the prime of life, eating a dish he had just invented. "

"What a pity!" said Michel. "And this dreadful accident claimed no other victims?"

"Oh yes, unfortunately, among others Jules Janin[38], a critic of the period who wrote Latin themes at the bottom of his columns. It was at a reconciliation dinner Dumas was giving him. And with them also perished a young writer, Monselet[39], who has left us a masterpiece, unfinished alas, the Dictionnaire des Gourmets, forty-five volumes and he only got as far as L—for larding."

"A shame, " said Michel, "it certainly sounds promising. "

"Now here is Frédéric Soulié[40], a brave soldier, good for a quick turn, and capable of seizing a desperate position, and Gozlan[41], a Captain of the Hussars, and Mérimée, a dressing-room General, and Sainte-Beuve, a Quartermaster General, in charge of supplies, and Arago, a learned officer in the engineers, who has managed to be forgiven for his knowledge. Look, Michel, here are the works of George Sand, a wonderful genius, one of the greatest writers of France, finally decorated in 1859 and giving her cross to her son to wear for her. "

"What are these forbidding-looking books?" asked Michel, pointing to a long row of volumes concealed by the cornice.

"Move on quickly, my child; that's the row of philosophers, Cousin[42], Pierre Leroux[43], Dumoulin, and so many more; but since philosophy is a matter of fashion, you won't be surprised that it's no longer read. "

"And who is this?"

"Renan. An archaeologist who caused a stir; he tried to deny the Divinity of Christ, and died thunderstruck in 1892. "

"And this one over here?"

"This one's a journalist, an economist, a ubiquist, an artillery General noisier than he was brilliant, by the name of Girardin.[44]"

"Wasn't he an atheist?"

"Not in the least; he believed in himself. Now look over here, a bold fellow, a man who would have invented the French language all over again if need be, and would be a classic today, if people still attended his classes: Louis Veuillot[45], the most vigorous champion the Roman Church ever had, and who died excommunicate, to his amazement. There's Guizot, an austere historian who in his spare time diverted himself by compromising the Orleans claim to the throne. And you see this enormous compilation? This is the only True and Authentic History of the Revolution and of the Empire, published in 1895 by order of the government to put an end to the various uncertainties which dismayed this part of our history. Thiers's chronicles were ransacked for this work. "

"Oh!" cried Michel, "here are some fellows who look young and eager. "

"Right you are; that's the light cavalry of 1860, brilliant, bold, noisy, overleaping prejudices like fences, dismissing the proprieties like barriers, falling, getting up again, and running all the faster, breaking their necks and fighting none the worse for it! Here's the masterpiece of the period, Madame Bovary, and Noriac's[46] Bêtise humaine, a vast subject he couldn't quite encompass; and here are the rest, Assollant[47], Aurevilly, Baudelaire, Paradol[48], Scholl[49], strapping fellows you have to watch out for no matter what, for they're likely to shoot you in the legs..."

"But only with gunpowder, " Michel concluded.

"Gunpowder mixed with salt, and that can sting. Now here's a fellow who has no lack of talent, a

real mascot of the troupe. "

"Edmond About[50]?"

"Yes! He flattered himself—or his public flattered him—he was going to begin Voltaire all over again, and in time he reached as far as his ankle; unfortunately in 1869, just when he was finishing his round of visits for the Académie-Française , he was killed in a duel by a fierce critic, the famous Sarcey.[51]"

"If this hadn't happened, would he have gone far?"

"Never far enough, " answered Uncle Huguenin. "Now these, my boy, are the principal leaders of our literary army: over there, the last rows of obscure soldiers whose names amaze the readers of old catalogs; continue your inspection, enjoy yourself; there are five or six centuries here that ask nothing better than to be glanced at!"

And that was how the day passed, Michel disdaining the unknowns to return to the illustrious names, but encountering odd contrasts, turning from a Gautier whose opalescent style had staled a little to a Feydeau, the licentious heir of Louvet[52] and Laclos, turning back from a Champfleury[53] to a Jean Macé[54], the ingenious popularizer of science. His eyes leaped from Méry[55], who produced wit the way a cobbler produces boots, on commission, to Banville, whom his Uncle Huguenin declared to be no more than a word juggler; then he came across Stahl[56], so scrupulously published by the house of Hetzel, and Karr, a witty moralist who nonetheless lacked the wit to let himself be pilfered, and Houssaye[57], who having in another life appeared at the Hotel de Rambouillet, had retained the absurd style and the précieux mannerisms of the place, and Saint-Victor[58], still flamboyant after a lifetime of a hundred years.

Then he returned to his point of departure; he took up several of these beloved volumes, opened them, read a sentence in one, a page in another, recited from this one only the chapter headings, and from that one only the titles; he inhaled that literary fragrance that rose to his brain like a warm emanation of bygone centuries, shaking hands with all these friends of the past he would have known and loved, had he had the wit to be born sooner!

Uncle Huguenin looked on, delighted by his nephew's pleasure, feeling younger just to watch him. "And what are you thinking now?" he asked him, when he saw Michel standing motionless, apparently in a trance.

"I'm thinking that this little room holds enough to make a man happy for his whole lifetime."

"If he can read. "

"I mean that kind of a man. "

"You're right, on one condition. "

"Which is?"

"That he not know how to write. "

"And why is that, Uncle?"

"Because then, my boy, he might be tempted to walk in the footsteps of these great writers."

"What would be wrong with that?"

"He would be lost. "

"Oh, Uncle!" Michel exclaimed, "you're going to draw a moral for me!"

"No, for if anyone deserves a lesson here, I'm the one.

"You! But why?"

"For having brought you into the presence of these wild ideas! I've given you a look at the Promised Land, my poor child, and—"

"And you will let me enter, won't you, Uncle?"

"Oh yes, if you will promise me one thing. "

"Which is..."

"Only to stroll through. I don't want you to be plowing this ungrateful soil! Remember what you are, what you need to do, what I am myself, and this day and age in which the two of us are living."

Michel made no reply but pressed his uncle's hand; and the latter was doubtless on the verge of repeating his tremendous arguments when the doorbell rang. Monsieur Huguenin went to answer it.

Chapter XI: A Stroll to the Port de Grenelle

It was Monsieur Richelot himself. Michel flung himself into the arms of his old teacher; a little more and he would have fallen into those Mademoiselle Lucy held out to Uncle Huguenin, who was fortunately standing at his post and thus forestalled that charming encounter.

"Michel!" exclaimed Monsieur Richelot.

"Himself, " Monsieur Huguenin reassured him.

"Ah!" exclaimed the professor, "now this is a happy surprise, and an evening which bodes laetanterly. "

"Dies albo nodanda lapillo, " riposted Monsieur Huguenin.

"As our dear Flaccus says, " Monsieur Richelot confirmed.

"Mademoiselle, " stammered the young man, greeting the young lady.

"Monsieur, " replied Lucy, with a curtsy that was not altogether clumsy.

"Candore notabilis albo," murmured Michel, to the delight of his professor, who forgave this compliment in a foreign tongue. Moreover the young man had spoken accurately; Lucy's entire charm was portrayed in that delicious Ovidian hemistich: remarkable for the luster of her whiteness! Mademoiselle Lucy was about fifteen and perfectly lovely, with long, blond curls falling over her shoulders in the fashion of the day, fresh and nascent, if that term can express about her what was new, pure, and blossoming; her deep blue eyes sparkling with naive glances, her pert nose with its tiny, transparent nostrils, her mouth moist with dew, the almost nonchalant grace of her neck, her cool and supple hands, the elegant outline of her figure— everything enchanted the young man and left him mute with admiration. The young lady was a living poem; he sensed rather than saw her; she touched his heart before delighting his eyes.

This little ecstasy threatened to last indefinitely; Uncle Huguenin realized as much, seated his visitors, managing to shield the young woman from the rays the poet was giving off, and began talking. "My friends, dinner will be served quite soon; let's chat awhile until it comes. You know, Richelot, it's been a good month since I've seen you. How are the humanities going?"

"They're going... away, " the old professor replied. "I have only three students left in my rhetoric class. It's a turpe[59] decadence! Soon they'll be getting rid of us, and with good reason."

"Getting rid of you!" Michel exclaimed.

"Can it really have come to that?" asked Uncle Huguenin.

"Really and truly, " Monsieur Richelot replied. "Rumor has it that the Literature professorships, by virtue of a decision taken in the General Assembly of the Stockholders, will be suppressed for the program of 1962. "

"What will become of them?" Michel wondered, staring at the girl.

"I can't believe such a thing, " said his uncle, frowning. "They wouldn't dare. "

"They will dare, " Monsieur Richelot replied, "and it will be for the best! Who cares about Greek and Latin? All they're good for is to provide a few roots for modern science. The students no longer understand these wonderful languages, and when I see how stupid these young people are, I don't know which I feel more intensely, despair or disgust!"

"Can it be possible, " asked young Dufrénoy, "that your class is reduced to three students?"

"Three too many, " grumbled the old professor.

"And all three of them dunces into the bargain, " said Uncle Huguenin.

"First-class dunces!" returned Monsieur Richelot. "Would you believe that just the other day one of them translated jus divinum as 'divine juice'?"

"Divine juice!" exclaimed Uncle Huguenin, "that's a budding drunkard you have there. "

"And yesterday, just yesterday! Horresco referens— guess, if you dare, how another one translated this verse from the fourth canto of the Georgics: immanis pecoris custos..."

"I'd say it was...," offered Michel.

"I blush for it to the tops of my ears, " said Monsieur Richelot.

"All right, tell us, " replied Uncle Huguenin. "How did he translate that passage in our year of grace 1961?"

" 'Guardian of a dreadful pecker, ' " replied the old professor, covering his face.

Uncle Huguenin could not contain a great burst of laughter; Lucy turned her head away, with a smile; Michel watched her sadly; Monsieur Richelot didn't know where to look.

"O Virgil!" exclaimed Uncle Huguenin, "would you ever have suspected such a thing?"

"You see what it is, my friends!" resumed the professor. "Better not to translate at all than to do it like this. And in a rhetoric class! Best to eliminate the who

le thing!"

"What will you do then?" asked Michel.

"That, my boy, is another question, but the moment has not arrived for an answer. We're here to have a good time—"

"Then let's have dinner, " interrupted Uncle Huguenin.

During preparations for the meal, Michel started a deliciously banal conversation with Mademoiselle Lucy, full of charming nonsense beneath which occasionally gleamed the traces of thought; at fifteen, Mademoiselle Lucy was entitled to be much older than Michel at sixteen, but she did not abuse the privilege. However, apprehensions for the future darkened her pure forehead and solemnized her expression. She gazed anxiously at her grandfather, who epitomized all of life to her. Michel intercepted one of these glances.

"You love Monsieur Richelot a great deal, " he said.

"A great deal, Monsieur. "

"So do I, Mademoiselle. " Lucy blushed slightly at seeing her affection and Michel's meet upon a mutual object; it was virtually a union of her most intimate feelings with those of another! Michel felt the same, and no longer dared look at her.

But Uncle Huguenin interrupted this tete-a-tete with a loud announcement that dinner was served. A neighborhood caterer had brought in a splendid meal ordered for the occasion. The guests took their places at the feast.

A thick soup and an excellent stew of boiled horse meat, a dish much esteemed up to the eighteenth century and restored to honor by the twentieth, contended with the diners' initial appetite; then came a leg of lamb prepared with sugar and saltpeter according to a new method which preserved the meat and added delicate qualities of flavor, garnished with several tropical vegetables now acclimatized in France. Uncle Huguenin's good humor and enthusiasm, Lucy's grace as she served the others, Michel's sentimental frame of mind—all contributed to making this family repast a charming occasion. However prolonged, it still ended too soon, and the heart was obliged to yield before the satisfactions of the stomach.

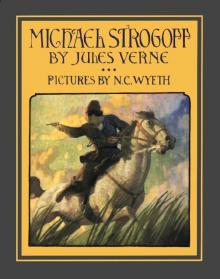

Michael Strogoff; Or the Courier of the Czar: A Literary Classic

Michael Strogoff; Or the Courier of the Czar: A Literary Classic Voyage au centre de la terre. English

Voyage au centre de la terre. English Journey Through the Impossible

Journey Through the Impossible The Castaways of the Flag

The Castaways of the Flag L'île mystérieuse. English

L'île mystérieuse. English Maître du monde. English

Maître du monde. English Around the World in Eighty Days

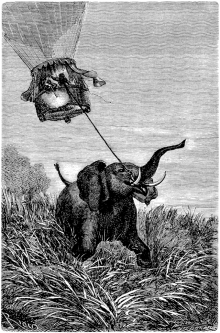

Around the World in Eighty Days A Voyage in a Balloon

A Voyage in a Balloon From the Earth to the Moon, Direct in Ninety-Seven Hours and Twenty Minutes: and a Trip Round It

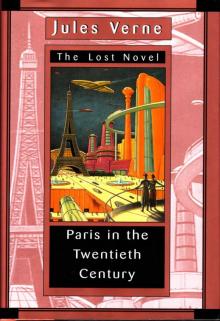

From the Earth to the Moon, Direct in Ninety-Seven Hours and Twenty Minutes: and a Trip Round It Paris in the Twentieth Century

Paris in the Twentieth Century City in the Sahara - Barsac Mission 02

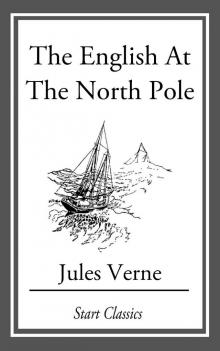

City in the Sahara - Barsac Mission 02 The English at the North Pole

The English at the North Pole The Field of Ice

The Field of Ice From the Earth to the Moon

From the Earth to the Moon Un capitaine de quinze ans. English

Un capitaine de quinze ans. English The Mysterious Island

The Mysterious Island Les indes-noirs. English

Les indes-noirs. English Robur-le-conquerant. English

Robur-le-conquerant. English Propeller Island

Propeller Island Around the World in Eighty Days. Junior Deluxe Edition

Around the World in Eighty Days. Junior Deluxe Edition Les forceurs de blocus. English

Les forceurs de blocus. English In the Year 2889

In the Year 2889 Journey to the Centre of the Earth

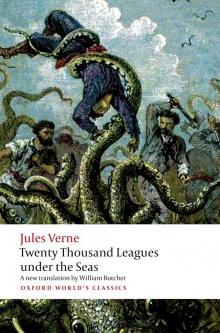

Journey to the Centre of the Earth Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea From the Earth to the Moon; and, Round the Moon

From the Earth to the Moon; and, Round the Moon Vingt mille lieues sous les mers. English

Vingt mille lieues sous les mers. English Cinq semaines en ballon. English

Cinq semaines en ballon. English Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas

Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas Face au drapeau. English

Face au drapeau. English Michael Strogoff; Or, The Courier of the Czar

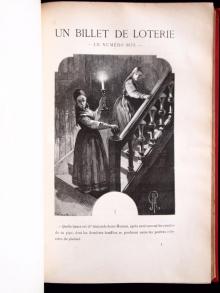

Michael Strogoff; Or, The Courier of the Czar Un billet de loterie. English

Un billet de loterie. English The Secret of the Island

The Secret of the Island Off on a Comet! a Journey through Planetary Space

Off on a Comet! a Journey through Planetary Space Into the Niger Bend: Barsac Mission, Part 1

Into the Niger Bend: Barsac Mission, Part 1 All Around the Moon

All Around the Moon A Journey to the Center of the Earth - Jules Verne: Annotated

A Journey to the Center of the Earth - Jules Verne: Annotated 20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 2

20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 2 Robur-le-Conquerant

Robur-le-Conquerant Les Index Noires

Les Index Noires Michael Strogoff; or the Courier of the Czar

Michael Strogoff; or the Courier of the Czar 20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 1

20000 Lieues sous les mers Part 1 Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Five Weeks In A Balloon

Five Weeks In A Balloon Journey to the Center of the Earth

Journey to the Center of the Earth 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday

Adrift in the Pacific-Two Years Holiday The Collected Works of Jules Verne: 36 Novels and Short Stories (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics)

The Collected Works of Jules Verne: 36 Novels and Short Stories (Unexpurgated Edition) (Halcyon Classics) The Survivors of the Chancellor

The Survivors of the Chancellor Their Island Home

Their Island Home Le Chateau des Carpathes

Le Chateau des Carpathes Les Cinq Cents Millions de la Begum

Les Cinq Cents Millions de la Begum The Floating Island

The Floating Island Cinq Semaines En Ballon

Cinq Semaines En Ballon Autour de la Lune

Autour de la Lune